European annual mean air

temperatures have increased by 0.3-0.6°C since 1900. Climate models

predict further increases, above 1990 levels, of about 2°C by the year

2100, with higher increases in the north of Europe than in the south.

The potential consequences include increases in sea level, more

frequent and intense storms, floods and droughts, and changes in biota

and food productivity. How serious these consequences will be depends

partly on the extent to which adaptation measures are implemented in

the coming years and decades.

Ensuring that further temperature increases are at

no more than 0.1°C per decade and that sea levels rise by no more than

2 cm per decade (provisional limits assumed for sustainability) would

require industrialised countries to reduce emissions of greenhouse

gases (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and various halogenated

compounds) by at least 30-55% by 2010 from 1990 levels.

Such reductions are much higher than the

commitments made by developed countries at the third conference of

parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

(UNFCCC) in Kyoto in December 1997, which were to reduce greenhouse gas

emissions in most European countries to 8% below the 1990 levels by

2010. Some CEE countries committed themselves to greenhouse gas

reductions of between 5% and 8% in 2010 compared with 1990, while the

Russian Federation and the Ukraine undertook to stabilise their

emissions at 1990 levels.

It is uncertain whether the EU will achieve the

original UNFCCC target, set in 1992, of stabilising emissions of carbon

dioxide (the most important greenhouse gas) in 2000 at 1990 levels,

because emissions in 2000 are currently predicted to be up to 5% above

1990 levels. Furthermore, in contrast to the Kyoto target of an 8%

reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in 2010 (for a "basket"

of six gases, including carbon dioxide), the Commission of the European

Communities’ latest "business as usual" (pre-Kyoto) scenario implies an

8% increase in carbon dioxide emissions between 1990 and 2010,

with the largest increase (39%) in the transport sector.

The proposal for one of the key measures at

Community level, an energy/carbon tax, has not yet been adopted, but

some Western European countries have already introduced such taxes

(Austria, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden). In

addition, there is scope for other types of measure to reduce

CO2 emissions, some of which are currently being taken by

various European countries and the EU. These include energy efficiency

programmes, combined heat and power installations, fuel switching from

coal to natural gas and/or wood, measures aimed at changing the modal

split in transport and measures aimed at absorbing carbon (increasing

the carbon sink) through afforestation.

Energy use, dominated by fossil fuels, is the key

influence on emissions of carbon dioxide. In Western Europe, emissions

of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel use fell by 3% between 1990 and

1995, due to economic recession, the restructuring of industry in

Germany and the switch from coal to natural gas for electricity

generation. Energy prices in Western Europe during the past decade have

been stable and relatively low compared to historical prices, providing

little incentive for improving efficiency. Energy intensity (final

energy consumption per unit of GDP) has fallen by only 1% per year

since 1980.

Patterns of energy use changed markedly between

1980 and 1995. Energy use in the transport sector grew by 44%,

industrial energy use fell by 8% and other fuel use grew by 7%,

reflecting mainly growth in road transport and a move away from

energy-intensive heavy industry. Total energy consumption increased by

10% between 1985 and 1995.

The contribution of nuclear energy to total energy

provision increased from 5 to 15% in Western Europe between 1980 and

1994, with Sweden and France depending on nuclear energy for around 40%

of their total energy requirements.

In Eastern Europe, carbon dioxide emissions from

fossil fuel use fell by 19% between 1990 and 1995, mainly as a result

of economic restructuring. Energy use for transport fell by 3% in CEE

over this period and by 48% in the NIS. Industrial energy use fell by

28% in CEE and by 38% in the NIS. Energy intensities in CEE are about

three times higher than in Western Europe and in the NIS probably five

times higher, so there is considerable potential for energy savings. In

a baseline "business as usual" scenario, energy use in 2010 is expected

to be 11% lower than in 1990 in the NIS, and 4% higher than in 1990 in

CEE.

The contribution of nuclear energy to total energy

provision increased from 2 to 6% in the NIS and by from 1 to 5% in CEE

between 1980 and 1994. In Bulgaria, Lithuania and Slovenia, nuclear

energy provides around a quarter of total energy requirements.

Methane emissions in CEE and the NIS fell by 40%

between 1980 and 1995. However, there is still considerable scope for

further reductions throughout Europe, particularly from gas

distribution systems and coal mining. Emissions of nitrous oxide from

industry and the use of mineral fertilisers could also be further

reduced throughout Europe.

Emissions of CFCs have fallen rapidly from their

peak levels as their production and use are phased out. However, the

use and emission of their substitutes, HCFCs (which are also greenhouse

gases), is increasing, as is that of relatively recently identified

greenhouse gases such as SF6, HFCs and PFCs, which are part

of the "basket" of gases for which emission reduction targets were

agreed at Kyoto.

CO2 emissions in Europe,

1980-1995

Source: EEA-ETC/AE

(Click on the image

to enlarge)

International policy

measures taken to protect the ozone layer have reduced global annual

production of ozone-depleting substances by 80-90% of its maximum

value. Annual emissions have also fallen rapidly. However, the time

delays in atmospheric processes are such that no effects of the

international measures can yet be seen in the concentrations of ozone

in the stratosphere or in the amount of ultraviolet-B (UV-B) radiation

reaching the surface.

The ozone-depleting potential of all chlorine and

bromine species (CFCs, halons, etc.) in the stratosphere is expected to

reach its maximum between 2000 and 2010. Above Europe, the amount of

ozone in the atmosphere fell by 5% between 1975 and 1995, allowing more

UV-B radiation to enter the lower atmosphere and reach the earth’s

surface.

Large localised reductions in stratospheric ozone

concentration have recently been observed over Arctic regions in the

spring. For example, total ozone over the North Pole fell to 40% below

normal in March 1997. These reductions are similar to, but less severe

than, those observed over Antarctica and emphasise the need for

continuing political attention to stratospheric ozone depletion.

The recovery of the ozone layer, which will take

many decades, could be accelerated by a more rapid phase-out of HCFCs

and methyl bromide, by ensuring the safe destruction of CFCs and halons

in stores and other reservoirs, and by preventing the smuggling of

ozone-depleting substances.

Ozone

depleting substances in the stratosphere, 1950-2100

Source: RIVM, preliminary data from

the WMO 1998 ozone assessment.

(Click on the image to enlarge)

There has been some reduction in the effects of

acid deposition originating from emissions of sulphur dioxide, nitrogen

oxides and ammonia on freshwater since the Dobris assessment,

with invertebrate fauna at many sites showing a partial recovery. The

vitality of many forests is still decreasing but, while this damage is

not necessarily related to acidification, long-term effects of acid

deposition on soils may be playing a role. In sensitive areas,

acidification leads to increased mobility of aluminium and heavy

metals, causing groundwater pollution.

Depositions of acidifying substances have decreased

since about 1985. Critical loads (the levels of deposition above which

long-term harmful effects can be expected) are, however, still being

exceeded in about 10% of Europe’s land area, mainly in northern and

central Europe.

Emission of sulphur dioxide in Europe halved

between 1980 and 1995. Total nitrogen emissions (nitrogen oxides plus

ammonia), which remained roughly constant between 1980 and 1990, fell

by about 15% between 1990 and 1995, the largest falls occurring in CEE

and the NIS.

The transport sector has become the largest source

of emissions of nitrogen oxides, contributing 60% of the total in 1995.

Between 1980 and 1994, road transport of goods increased by 54%;

between 1985 and 1995, road transport of passengers increased by 46%

and air transport of passengers by 67%.

In Western Europe, the introduction of exhaust

catalysts has resulted in reduced emissions from the transport sector.

However, such measures take effect rather slowly because of the low

turnover rate of the vehicle fleet. Further reductions are likely to

require fiscal measures on fuels and vehicles.

In CEE and the NIS, there is significant potential

for growth in private transport, but also major potential for improving

energy efficiency throughout the transport sector.

Policy measures to combat acidification have been

only partly successful:

- The of the protocol of the Convention on

Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (CLTRAP) on nitrogen oxides, to

stabilise emissions at the 1987 level by 1994, was achieved for Europe

overall, but not by all the 21 parties. Some of the parties, however,

as well as non-parties, achieved considerable reductions.

- The Fifth Environmental Action Plan of the

European Commission (5EAP) aimed for a 30% reduction of emissions of

nitrogen oxides between 1990 and 2000. Only an 8% reduction was

achieved by 1995, and it does not appear likely that the 2000 will be

met.

A multi-pollutant, multi-effect protocol is

expected to be ready in 1999. The aim will be to set further national

emission ceilings, on a cost-effective basis, for acidifying substances

and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs).

- The target of the first CLRTAP protocol for

sulphur, to reduce emissions in 1993 by 30% compared to 1980,

was achieved by all 21 parties to the protocol, as well as by five

non-parties. However, several European countries (for example, Portugal

and Greece) did not reduce their sulphur emissions in this period to

the same extent. Achieving the interim

target of the second sulphur protocol by 2000 is more uncertain, and

further measures will be needed to achieve its long-term target, which

is no exceedance of critical loads.

- The 5EAP target for sulphur dioxide, a

reduction of 35% of 1985 emissions by 2000, was achieved for the EU as

a whole in 1995 (40% overall reduction) and by most Member

States.

Further measures aimed at reaching the long-term

target of the second CLRTAP sulphur protocol are under development in

the EU, following the 5EAP, including reducing the sulphur content of

oil products, reducing emissions from large combustion plants and

setting emission limits for road vehicles. A provisional target of the

EU acidification strategy now under discussion is a 55% reduction in

emissions of nitrogen oxides between 1990 and 2010. Particular

attention will need to be paid to emissions from the transport sector

if this target is to be met.

Total area of exceedance of the

critical load for sulphur and nitrogen

Source: EMEP/MSC/W and

CCE

(Click on the image to enlarge)

Ozone concentrations in the troposphere (from the

ground to 10-15km) over Europe are typically three to four times higher

than in the pre-industrial era, mainly as a result of the very large

growth in emissions of nitrogen oxides from industry and vehicles since

the 1950s. Year-to-year meteorological variability prevents the

detection of trends in the occurrence of episodes of high ozone

concentration.

Threshold concentrations, set for the protection of

human health, vegetation and ecosystems, are frequently exceeded in

most European countries. About 700 hospital admissions in the EU in the

period March-October 1995 (75% of them in France, Italy and Germany)

may be attributable to ozone concentrations exceeding the health

protection threshold. About 330 million people in the EU may be exposed

to at least one exceedance of the threshold per year.

The protection threshold for vegetation was

exceeded in most EU countries in 1995. Several countries reported

exceedances for more than 150 days at some sites. In the same year,

almost the entire EU area of forest and arable land experienced

exceedances.

Emissions of the most important ozone precursors,

nitrogen oxides and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs),

increased until the late 1980s and then fell by 14% between 1990 and

1994. The transport sector is the main contributor of nitrogen oxides.

Transport is also the main contributor to emissions of NMVOCs in

Western Europe, while in CEE and the NIS, industry is the main

contributor.

Meeting the for emissions of nitrogen oxides set in

the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution’s and the

Fifth Environmental Action Programme would result in a reduction in

peak ozone concentrations of only 5-10%. Achieving the long-term target

of no exceedance of threshold levels will depend critically on reducing

overall tropospheric ozone concentrations. This will require measures

on emissions of the precursor pollutants (nitrogen oxides and NMVOCs)

covering the whole of the northern hemisphere. A first step will be the

setting of further national emission ceilings under the new

multi-effect, multi-pollutant protocol.

Daily summer

maximum concentrations of ozone

Source: EEA-ETC/AQ

(Click on the image to enlarge)

Since the Dobris assessment, the chemical

industry in Western Europe has continued to grow, with production since

1993 growing faster than GDP. Production in CEE and the NIS has fallen

markedly since 1989, in line with the fall in GDP, but since 1993

production has partially recovered in some countries. The net result is

that the flows of chemicals through the economy throughout Europe have

increased.

Data on emissions is scarce, but chemicals are

widespread in all environmental media, including animal and human

tissues. The European Inventory of Existing Chemical Substances lists

over 100 000 chemical compounds. The threat posed by many of these

chemicals remains uncertain because of the lack of knowledge about

their concentrations and the ways in which they move through and

accumulate in the environment and then impact on humans and other life

forms.

Some information, however, is available – for

example, on heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants (POPs).

Although emissions of some of these substances are falling,

concentrations in the environment remain of concern, particularly in

some highly contaminated areas and sinks like the Arctic and Baltic

Sea. Although some well-known POPs are being phased out, many others

with similar properties are still being produced in large amounts.

Concerns have recently been raised about so-called

"endocrine disrupting substances": POPs and some organo-metallic

compounds, particularly as a possible cause of reproductive

disturbances in wildlife and humans. While there are examples of such

effects in marine animals, there is so far insufficient evidence to

establish causal links between such chemicals and reproductive health

effects in humans.

Because of the difficulty and cost of assessing the

toxicity of the large numbers of potentially hazardous chemicals in

use, particularly those with possible reproductive and

neuro-toxicological effects, some current control strategies – such as

the one chosen by the OSPAR Convention on the protection of the North

Sea – are now aimed at reducing the "load" of chemicals in the

environment through the elimination or reduction of their use and

emissions. The UNECE is expected to finalise two new protocols on

emissions to air of three heavy metals and sixteen POPs under the

Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution in 1998.

Since the Dobris assessment, there have

been some new national and international initiatives for reducing the

possible impacts of chemicals on the environment, including voluntary

reduction programmes, taxation of particular chemicals and providing

public access to data similar to the US Toxic Release Inventory, as for

example under the Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control Directive

in the EU. There is scope for a wider application of such instruments

in all parts of Europe.

Reductions of lead emissions from petrol

1990-1996

Source: Danish EPA

(Click on the image to enlarge)

Reported total waste generation in OECD Europe

increased by nearly 10% between 1990 and 1995. However, part of the

apparent increase may be the result of improved waste monitoring and

reporting. Lack of harmonisation and incomplete data collection

continue to make it difficult to monitor trends and improve the of

waste policy initiatives across Europe.

Municipal waste generation is estimated to have

increased by 11% in OECD European countries between 1990 and 1995.

Approximately 200 million tonnes of municipal waste was generated in

1995, equivalent to 420 kg/person/year. Data on municipal waste for CEE

countries and the NIS are not sufficiently robust to enable the

determination of an underlying trend.

Germany and France were the largest contributors to

the approximately 42 million tonnes per year of hazardous waste

reported by OECD European countries for the period around 1994. The

Russian Federation accounted for about two-thirds of the 30 million

tonnes of hazardous waste generated per year by the whole of Eastern

Europe during the early 1990s. These totals are only indicative because

of differences in definition.

Waste management in most countries continues to be

dominated by the cheapest available option: landfill. However, the

costs of landfill rarely include full costs (post-closure costs are

seldom included), despite the use of waste taxes in some countries

(e.g. Austria, Denmark and the UK). Waste prevention and minimisation

is being increasingly recognised as environmentally more desirable

solutions for waste management. All waste streams, particularly

hazardous wastes, would benefit from further application of cleaner

technologies and waste prevention measures. Recycling is increasing in

countries with strong waste management infrastructures.

Many countries in CEE and the NIS face the problems

of a legacy of poor waste management and increases in waste generation.

Waste management in these countries requires better strategic planning

and more investment. Priorities include improving municipal waste

management through better separation of wastes and better landfill

management, the introduction of recycling initiatives at local level

and carrying out low-cost measures to prevent soil contamination.

A commitment to the sustainable use of resources,

minimising environmental damage and following the "polluter pays

principle" and the "proximity principle" has led the EU to create an

extensive range of legislative instruments intended to promote and

harmonise national legislation on waste. Some Central European

countries are beginning to adopt similar approaches, prompted by the EU

accession process. However, waste legislation is still poorly developed

in most other CEE countries and in the NIS.

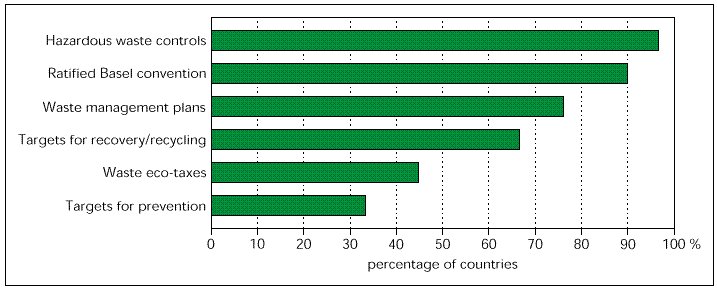

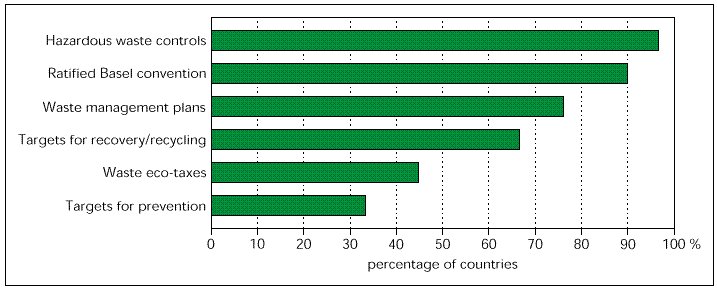

Share of countries with the following

instruments in waste policy

Source: EEA

The threat to Europe’s wild species continues to be

severe and the number of species in decline is growing. In many

countries, up to half of the known vertebrate species are under

threat.

More than one-third of the bird species in Europe

are in decline, most severely in north-western and central Europe. This

is mainly caused by damage to their habitats by land-use changes,

particularly through intensification of agriculture and forestry,

increasing infrastructure development, water abstraction and

pollution.

However, the populations of a number of animal

species associated with human activities are increasing and some plant

species tolerant to high nutrient levels or acidity are spreading.

There has also been some recovery in the number of breeding birds in

areas where organic farming is practised. The introduction of alien

species is causing problems in marine, inland water and terrestrial

habitats.

Wetland loss is greatest in southern Europe, but

major losses are also occurring in many agricultural and urbanised

areas in north-western and central Europe. The main causes are land

reclamation, pollution, drainage, recreation and urbanisation. Some

large and many minor restoration projects in rivers, lakes, bogs and

mires are, to some extent, compensating for these losses, though mostly

on a small scale.

The extent of sand dunes has fallen by 40% this

century, mainly in along the western shores of Europe; a third of the

loss has occurred since mid 1970s. The main causes are urbanisation,

recreational use and forest plantation.

The total area of forest is increasing, as is total

timber production. "Extensive" forest management, formerly the most

common practice, continues to be replaced by more intensive and uniform

management. The use of exotic species is still increasing. The severe

loss of old natural and semi-natural woodlands has continued. Most of

the old and almost untouched forests are now to be found in CEE and the

NIS, although smaller areas still exist elsewhere. Forest fires are

still a problem around the Mediterranean, though there has been a

decrease in the area affected. The concept of sustainable forestry is

beginning to be introduced in forest use and management, but general

effects on biodiversity have yet to be seen.

As agriculture has become more intensive and

afforestation has continued in low-yielding areas, semi-natural

agricultural habitats such as meadows are rapidly being lost or

degraded. These habitats were formerly very widespread in Europe and

depended on extensive agricultural management with low inputs of

nutrients. They now suffer from excessive nutrient input and

acidification. With the disappearance of their often very rich plant

and animal life, the natural biodiversity of the open landscape has

severely diminished.

A wide range of initiatives and legal instruments

for the protection of species and habitats has been introduced

internationally and nationally in all countries. All these have

succeeded in protecting considerable land and sea areas and saving a

number of species and habitats, but implementation is often difficult

and slow and has not been able to counteract the general decline. At

European level, the implementation of the Natura 2000 network of

designated sites in the EU, and the upcoming EMERALD network under the

Bern Convention in the rest of Europe, are currently the most important

initiatives.

Overall, the conservation of biodiversity is often

regarded as less important than the shorter-term economic or social

interests of the sectors influencing it most heavily. A major obstacle

to securing conservation goals remains the need to incorporate

biodiversity concerns into other policy areas. Strategic Environmental

Assessments for policies and programmes, together with nature

conservation instruments, can be important tools for enhancing such

integration.

Bird

status

Source: EEA-ETC/NC

(Click on the image to enlarge)

There has been a general reduction in total water

abstraction in many countries since 1980. In most countries, industrial

abstraction has been falling slowly since 1980 because of the shift

away from industries that are heavy users of water, the growth of

services, technical improvements and increased recycling. However,

demand around urban areas may still exceed availability and, in the

near future, water shortages may occur. Future water supply may also be

affected by climate change.

Agriculture is the most important user of water in

Mediterranean countries, mainly for irrigation. The area under

irrigation and the abstraction of water for irrigation have been rising

steadily since 1980. In southern European countries, 60% of all water

abstracted is used for irrigation. In some regions, groundwater

abstraction is exceeding the recharge rate, causing lowering of the

groundwater table, loss of wetlands and seawater intrusion. Tools for

limiting future demand for water include improvements in the efficiency

of water use, price controls and agricultural policy.

Despite the introduction of water quality in the EU

and the attention to water quality in the Environmental Action

Programme for Central and Eastern Europe, there has been no overall

improvement of river quality since 1989/90. European countries report

different trends without any consistent geographical pattern. There

have been some improvements in the most seriously polluted rivers,

however, since the 1970s.

Phosphorus and nitrogen continue to cause

eutrophication of surface waters. Improvements in waste-water treatment

and reductions in emissions from large industries between 1980 and 1995

resulted in total discharges of phosphorus into rivers falling by

between 40% and 60% in several countries. Phosphorus concentrations in

surface waters decreased significantly, particularly in those

previously most severely affected. Further improvements are expected

since the recovery time, particularly of lakes, may be several years.

Phosphorous concentrations at about a quarter of the river monitoring

sites are still about ten times higher than those in water of good

quality. Nitrogen, of which the main source is agriculture, is less of

a problem in rivers, but can cause problems when transported to the

sea; emissions need to be further controlled to protect the marine

environment.

Groundwater quality is affected by increasing

concentrations of nitrate and pesticides from agriculture. Nitrate

concentrations are low in northern Europe, but high in several Western

and Eastern countries, with frequent exceedances of the EU maximum

admissible concentration.

The application of pesticides in the EU fell

between 1985 and 1995, but this does not necessarily indicate a

decrease in environmental impact since the range of pesticides in use

has changed. Groundwater concentrations of certain pesticides

frequently exceed EU maximum admissible concentrations. Significant

pollution from heavy metals, hydrocarbons and chlorinated hydrocarbons

has also been reported from many countries.

Integrated polices for the protection of inland

waters are in place in many areas of Europe, for example around the

North Sea, the Baltic Sea, the Rhine, the Elbe and the Danube. Although

much has been achieved, better integration of environmental policies

with economic policies remains a challenge for the future.

Agricultural policy, in particular, will be the key

for tackling inputs from diffuse sources, but this continues to be both

technically and politically difficult. Although reform under the Common

Agricultural Policy of the European Union is being used to integrate

measures to reduce nutrient inputs, more will have to be done – for

example, to ensure that policies such as setting aside agricultural

land are designed to maximise environmental benefits.

The EU Urban Waste Water Treatment and Nitrate

Directives should deliver substantial quality improvements, but their

success depends on the extent to which Member States designate

sensitive areas and vulnerable zones. The proposal for a Water

Framework Directive will require integrated programmes of management

and improvement. If implemented in a comparable way across the EU, this

Directive, coupled with a further switch to demand-side management,

should lead to marked improvements in water quality and to the

sustainable management of water resources.

Freshwater availability in Europe

Source: Eurostat, OECD,

Institute of Hydrology

(Click on the image to enlarge)

The most threatened seas are the North Sea

(over-fishing, high nutrient and pollutant concentrations), the Iberian

seas (i.e. the part of the Atlantic along the eastern Atlantic shelf,

including the Bay of Biscay: over-fishing, heavy metals), the

Mediterranean sea (locally high nutrient concentrations, high pressure

on the coasts, over-fishing), the Black Sea (over-fishing, rapid

increase of nutrient concentrations) and the Baltic Sea (high nutrient

concentrations, pollutants, over-fishing).

Eutrophication, mainly resulting from nutrient

surpluses in agriculture, is of major concern in some parts of many

European seas. Nutrient concentrations are generally at the same level

as in the beginning of the 1990s. Increases in nitrogen discharges and

resulting concentrations in sea water on some of the west coasts of

Europe seem to be correlated with high precipitation and flooding

between 1994 and 1996. In most other seas, no clear trend in nutrient

concentrations could be identified. However, concentrations of

nutrients in the Black Sea, mainly originating from the Danube

watershed, increased about tenfold between 1960 and 1992.

Contamination of sediments and biota by

anthropogenic chemicals seems to be common in almost all European seas.

Only limited data was available, mainly covering western and

north-western Europe. Elevated concentrations (above natural

background) of heavy metals and PCBs have been found in fish and

sediment, with high levels near point sources of emission.

Bio-accumulation of these substances may pose a threat to ecosystems

and human health (as discussed in the chapter on chemicals).

The overall picture of oil pollution is highly

fragmentary, and no reliable assessment of general trends can be made.

The main source is from land, reaching the seas through rivers.

Although the annual number of oil spills is falling, small and

occasional large spills in zones of heavy boat traffic are causing

significant local damage, primarily smothering of beaches and seabirds

and impairment of harvest of fish and shellfish. There is, however, no

evidence of irrevocable damage to marine ecosystems, either from major

spills or from chronic sources of oil.

Many seas continue to be heavily over-fished, with

particularly serious problems in the North Sea, the Iberian seas, the

Mediterranean and the Black Sea. There is a critical over-capacity in

the fishing fleet, and a reduction of 40% in capacity would be needed

to match available fish resources.

Nitrogen and phosphorus discharges

Source: EEA - ETC/MC

(Click on the image to enlarge)

Over 300 000 potentially contaminated sites have

been identified in Western Europe, and the estimated total number in

Europe is much greater.

Although the Environmental Programme for Europe

called for the identification of contaminated sites, a complete

overview is not yet available for many countries. The extent of the

problem is difficult to assess because of the lack of agreed

definitions. The European Commission is preparing a White Paper on

environmental liability; follow-up actions might require agreed

definitions. Most Western European countries have established

regulatory frameworks aimed at preventing future incidents and cleaning

up existing contamination.

In Eastern Europe, soil contamination around

abandoned military bases poses the most serious risk. The majority of

the countries in the region have started to assess the problems

involved. However, many CEE countries and the NIS have still to develop

the regulatory and financial framework needed for dealing with

contaminated sites.

Another severe problem is soil loss through sealing

under constructions, such as industrial premises and transport

infrastructure, reducing soil use options for future generations.

Soil erosion is increasing. About 115 million

hectares are suffering from water erosion and 42 million hectares from

wind erosion. The problem is greatest in the Mediterranean region

because of its fragile environmental conditions, but problems exist in

most European countries. Soil erosion is intensified by land

abandonment and forest fires, particularly in marginal areas.

Strategies, such as afforestation, for combating accelerated soil

erosion are lacking in many areas.

Soil salinisation is affecting nearly 4 million

hectares, mainly in Mediterranean and Eastern European countries. The

main causes are over-exploitation of water resources as a result of

irrigation for agriculture, population increase, industrial and urban

development and the expansion of tourism in coastal areas. The main

effects in cultivated areas are lower crop yields and even total crop

failure. Strategies to combat soil salinisation are lacking in many

countries.

Soil erosion and salinisation have increased the

risk of desertification in the most vulnerable areas, particularly in

the Mediterranean region. Information on the extent and severity of

desertification is limited; further work is needed on prevention

strategies, possibly within the framework of the United Nations

Convention to Combat Desertification.

Available data on the number of

certain and potentially contaminated sites

|

Industrial

sites |

Waste

sites |

Military sites |

Potentially contaminated |

Contaminated sites |

|

abandoned |

operating |

abandoned |

operating |

|

identified |

estimated total |

identified |

estimated total |

|

| Albania |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

78 |

|

| Austria |

|

|

|

|

|

28 000 |

~80 000 |

135 |

~1 500 |

|

| Belg/Flan. |

|

|

|

|

|

4 583 |

~9 000 |

|

|

| Belg/Wall. |

|

|

|

|

|

1 000 |

5 500 |

60 |

|

|

| Denmark |

|

|

|

|

|

37 000 |

~40 000 |

3 673 |

~14 000 |

| Estonia |

|

|

|

|

|

~755 |

|

|

|

|

| Finland |

|

|

|

|

|

10 396 |

25 000 |

1 200 |

|

| France |

|

|

|

|

|

|

300 000 |

895 |

|

|

| Germany |

|

|

|

|

|

191 000 |

~240 000 |

|

|

| Hungary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

600 |

10 000 |

|

| Italy |

|

|

|

|

|

8 873 |

|

1 251 |

|

| Lithuania |

|

|

|

|

|

~1 700 |

|

|

|

|

| Luxemburg |

|

|

|

|

|

616 |

|

175 |

|

| Netherlands |

|

|

|

|

|

|

110 000

-120 000 |

|

|

|

| Norway |

|

|

|

|

|

2,300 |

|

|

|

| Spain |

|

|

|

|

|

4 902 |

|

370 |

|

|

| Sweden |

|

|

|

|

|

7 000 |

|

2 000 |

|

| Switzerland |

|

|

|

|

|

35 000 |

50 000 |

~3 500 |

|

|

| UK |

|

|

|

|

|

|

~ 100 000 |

|

~ 10 000 |

|

Source: EEA-ETC/S

Urbanisation is continuing, despite the fact that

around three-quarters of the population of Western Europe and the NIS,

and slightly less than two-thirds of that in CEE, already live in

cities.

The rapid increase in private transport and

resource-intensive consumption are major threats to the urban

environment and, consequently, to human health and welfare. In many

cities, cars now provide over 80% of mechanised transport. Forecasts of

transport growth in Western Europe indicate that, for a "business as

usual" scenario, road transport demands for passengers and freight

could nearly double between 1990 and 2010, with the number of cars

increasing by 25-30% and annual kilometres per car increasing by 25%.

The current growth in urban mobility and car ownership in CEE cities is

expected to accelerate during the next decade, with corresponding

increases in energy consumption and transport-related emissions.

Overall, air quality in most European cities has

improved. Annual lead concentrations dropped sharply in the 1990s

because of the reduction in the lead content of petrol, and there seems

to be evidence that concentrations of other pollutants are also

falling. However, a few CEE cities have reported small increases in

lead concentrations during the past five years, due to the increase in

traffic. The envisaged phase-out of leaded petrol would solve this

problem.

Ozone remains a major problem in some cities,

however, with high concentrations occurring during the whole of the

summer. A majority of cities providing data report exceedances of WHO

guideline values for sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides

and particulate matter (PM). Little data was available on benzene, but

exceedance of WHO air quality guideline values seems common.

Extrapolation of the reported results to all 115

large cities of Europe suggests that about 25 million people are

exposed to winter smog conditions (exceedances of air quality

guidelines for SO2 and PM). The corresponding number of people exposed

to summer smog conditions (related to ozone) is 37 million, with nearly

40 million people experiencing at least one exceedance of the WHO

guidelines every year.

In Western Europe, the dominant sources of air

pollution – previously industrial processes and the combustion of coal

and high-sulphur fuels – are now motor vehicles and the combustion of

gaseous fuels. As transport is expected to increase considerably,

transport-related emissions are also expected to rise, intensifying air

pollution in cities. In CEE and the NIS, similar shifts are occurring,

but at a slower pace.

About 450 million people in Europe (65% of the

population) are exposed to high environmental noise levels (above

Equivalent Sound Pressure Levels (Leq) 24h 55dB(A)). About 9.7 million

people are exposed to unacceptable noise levels (above Leq 24h

75dB(A)).

Water consumption in a number of European cities

has increased: about 60% of large European cities are over-exploiting

their groundwater resources and water availability, and water quality

may increasingly constrain urban development in countries where there

are shortages, particularly in southern Europe. Several cities in

northern Europe, however, decreased their water consumption. In

general, the water resource could be more effectively used, since only

a small percentage of domestic water use is for drinking or cooking,

and large amounts (5% to over 25%) are lost by leakage.

Urban problems are not confined to the cities

themselves. Growing areas of land are needed to provide the populations

of large cities with all the resources they need and to absorb the

emissions and wastes they produce.

In spite of progress in setting up environmental

management in European cities, many problems remain unresolved. During

the past five years, an increasing number of city authorities have been

exploring ways of achieving sustainable development in the context of

local Agenda 21 policies, which may include measures to reduce the use

of water, energy and materials, better planning of land use and

transportation, and the use of economic instruments. More than 290

cities have already joined the European Sustainable Cities and Towns

Campaign.

Data on many aspects of the urban environment – for

example, water consumption, municipal waste generation, waste-water

treatment, noise and air pollution – is still incomplete and inadequate

for a comprehensive assessment of changes in the urban environment in

Europe.

Annual

average NO2 concentrations, 1990-95

Source: EEA-ETC/AQ

(Click on the image to enlarge)

In the EU, the number of major industrial accidents

reported each year has been roughly constant since 1984. Since both the

notification of accidents and the level of industrial activity have

increased since then, it is likely that the number of accidents per

unit of activity has decreased. No accident databases currently cover

CEE or the NIS.

On the basis of the International Nuclear Event

Scale (INES) of the International Atomic Energy Agency, there have been

no "accidents" (INES levels 4-7) in Europe since 1986 (Chernobyl – INES

level 7). Most of the reported events have been "anomalies" (INES level

1), with a few "incidents" (INES levels 2-3).

There has been a significant worldwide reduction,

during the past ten years, in the annual number of large oil spills.

However, in the last few years three of the largest spills in the world

ever have occurred in Western Europe. The very large spills that did

occur were responsible for a high percentage of the oil spilt.

There is a continuing increase in the intensity of

many activities that can give rise to major accidents and a growing

vulnerability of some of these activities and infrastructures to

natural hazardous events. The Seveso II Directive, with its wide

coverage and comprehensive nature and its focus on accident prevention,

provides much of the framework necessary for better risk management.

This now needs to be implemented by industries and regulatory and

planning authorities. It also provides a model for Eastern Europe,

where no such broad trans-national framework exists. However, there is

also a general need to address other than industrial risks.

Exceptionally large numbers of floods have occurred

during the 1990s, causing much damage and many deaths. While the most

likely explanation is natural variations in water flow, the effects may

have been amplified by human impacts on the hydrological cycle.

Oil spills in

Europe, 1970-1996

Source: ITOPF

(Click on the image to enlarge)

Document Actions

Share with others