Monitoring the circular economy

The circular economy is one where ‘the value of products and materials is maintained for as long as possible, and waste and resource use are minimised’, as set out in the European Commission’s circular economy action plan.

The European Commission and Eurostat have established a framework to monitor progress towards a circular economy using available statistical data. This framework focuses on aspects of the circular economy related to resource use and waste management. Aspects related to maintaining the value of products and materials for longer — such as design for circularity, repair, reuse and circular consumption — are not yet included. The circular economy action plan aims to improve the current monitoring system. All key aspects of the circular economy should be included in the monitoring system to fully capture progress and inform decision-makers.

The Bellagio principles on monitoring the circular economy were developed under the auspices of the Network of the Heads of Environmental Protection Agencies in Europe and were referenced by the EU Council in December 2020. The principles support the establishment of a comprehensive monitoring framework capturing all relevant elements of the circular economy. They include the following key points (see Figure 1):

Principle 3: Follow indicator selection criteria. Indicators included in a transparent monitoring framework for the circular economy transition should follow the RACER criteria: relevant, accepted, credible, easy to monitor and robust. However, development of innovative, experimental indicators should also be encouraged, even if not all RACER criteria are fulfilled at first.

Principle 4: Exploit a wide range of data and information sources. Data underpinning a framework for monitoring the circular economy transition may include:

- official statistics from the European Statistical System or national statistical offices and other data produced by EU institutions, national or local authorities and international organisations

- policy information (from tracking policy developments and implementation, including qualitative assessments)

- data from new sources (i.e. information beyond official statistics, such as data from the private sector and trade associations, from research models, or from new applications of digital technologies).

Source: Bellagio Declaration. EPA network.

Thus, while principles 3 and 4 call for using strict criteria and statistics from mainly official sources, they also fully recognise the need for further development and experimentation as a tool to fill some of the gaps in the monitoring framework.

Potential innovative ways to measure circularity in Europe

Against this backdrop the EEA has, with the support of the European Topic Centre for Waste and Materials in the Green Economy, identified examples of new sources of data that can be collected to provide useful estimates for monitoring important elements of the circular economy transition.

Browser fingerprints

Many devices are connected to the internet to enable them to retrieve or share information and receive software updates. The most obvious examples are mobile phones, laptops and television sets, but cars and many home appliances are also gradually being connected as the software content of these devices increases and the ‘internet of things’ expands.

When these devices connect to websites, they leave a fingerprint with information that enables sites to tailor information to that particular device. This information includes the type of device and software version. By harvesting this fingerprint, it is possible to determine the age distribution of devices in current use, and these data can be used to estimate the service life of devices.

However, using such data may face a number of obstacles:

- Different operating systems vary in how they implement the fingerprint. There is, for example, a big difference between the structure and content of the fingerprint left by an Android phone and an iOS (Apple) phone. This makes harvesting more complex.

- In many cases it is difficult to determine a device’s geographical location. Therefore, statistics derived from the analysis will tend to be global in nature rather than European or national. It is possible to get national estimates by harvesting fingerprints obtained from websites heavily used by the population (e.g. weather websites), but this method is far from perfect.

- The fingerprint, as it is implemented in mobile phones, does not include a date of first use. Instead, it is possible to establish the maximum age of each device based on when a particular model came on to the market. This means that data provide only an upper-end estimate of the age distribution of phones in use. However, as new phone models are frequently put on the market, it still allows a good approximation of the age distribution.

Note: Small data set used for illustration only and not necessarily representative of the entire phone population.

More info...

Car sharing system — a case study from Germany

Car sharing is seen as an environmentally friendly alternative to car ownership, as it generally involves the more efficient use of smaller cars than people would otherwise buy. As each shared car is used more often than an owned car it wears out faster, leading to a faster renewal of the car fleet, meaning that cleaner vehicles gain a larger market share faster. However, car sharing may be competing with public transport rather than replacing privately owned cars, and so the lifetime environmental credentials of car sharing are not always clear.

German car sharing clubs have centralised the collection of data on the use of shared vehicles. The EEA has assessed whether this data set could be used to develop estimates of car sharing in countries where no such data exist.

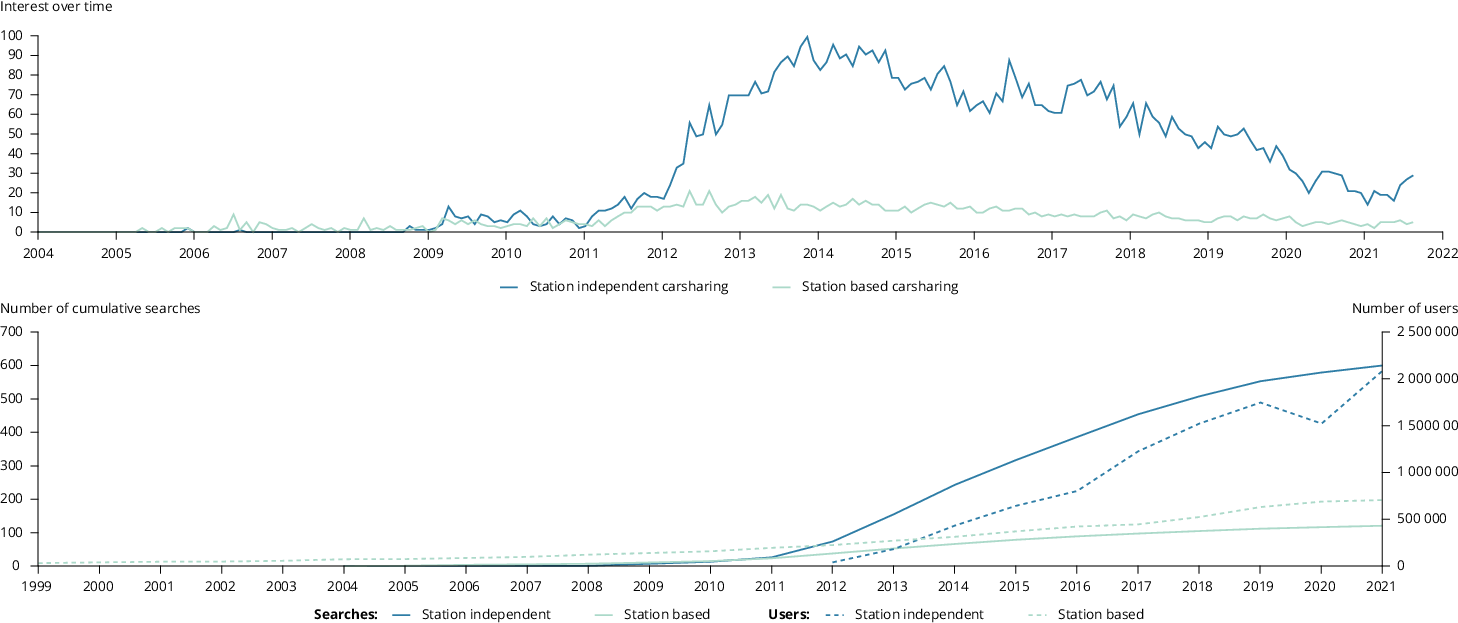

It is possible to see how often people search online for terms related to car sharing using Google Trends (see Figure 3). It can also be assumed that people search for information, decide to become a user, and then have little or no need to search again.

Note: The 2020 dip is likely to be due to the COVID-19 pandemic, when people may have stopped paying a subscription because they could not travel anywhere.

More info...

There is a clear correlation between car sharing membership and cumulative searches, and this indicates that the number of searches could serve as an estimate of the use of such services. Search results will not provide absolute market performance data. However, they can illustrate knowledge about and interest in the concept and, together with very limited market data, indicate the performance of the car sharing sector.

Web scraping electronic and electrical appliances

An important element of EU policy on the circular economy is the ‘right to repair’. But having the right is not the same as having the ability, and an important aspect is having access to knowledge about how things are repaired. In the context of modern mass production, it is often cheaper to buy a new product than to get it professional repaired. The ability to extend the lifetime of products by repairing them may therefore hinge on people’s ability to do their own repairs.

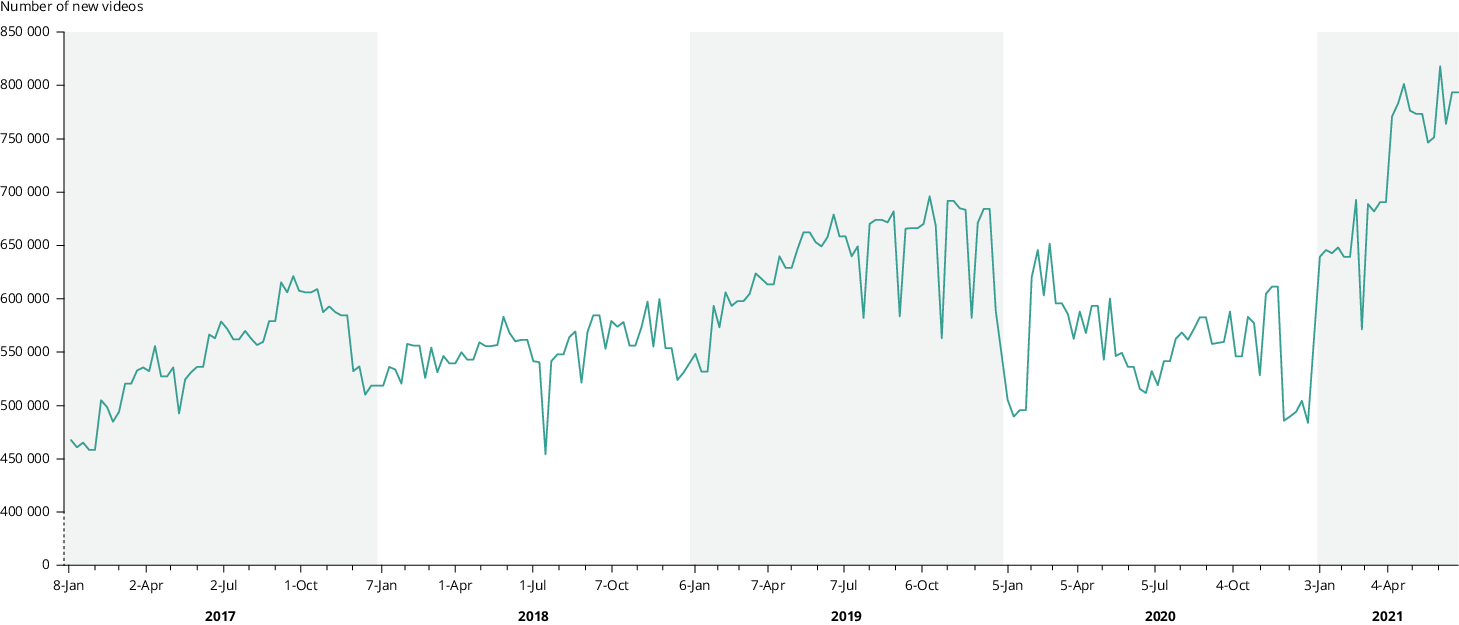

Many people share videos online showing how to repair specific products, ranging from general videos on, for example, changing a mobile phone screen, to very detailed ones relating to a specific manufacturer’s product. Online video sharing services capture the number of views of individual videos, making it possible to assess interest in particular topics, although it is not known if this translates to actual repairs (see Figure 4).

The real challenge for indicator development lies in establishing a list of relevant search terms so that a measure captures a relevant set of videos. Therefore, an index based on the number of videos and number of views may indicate interest in attempting a repair.

More info...

Web scraping could be used for a range of other topics, such as green claims posted by companies online (e.g. are companies making reference to refurbished elements and repairability?). This may enable the development of a range of indicators that have not yet been tested.

Repair case study

Sweden is an example of a Member State that offers a tax break for professional repair activities. Taxpayers are required to report repairs to obtain the tax deduction, and the data are collected by the tax authority and made publicly available. This is an easy-to-use data source, but one that is not widely available across EU Member States. Judging by the data from Sweden, it is likely that the rules changed in 2016, as it is otherwise difficult to explain the significant change in trend in that year (see Figure 5).

More info...

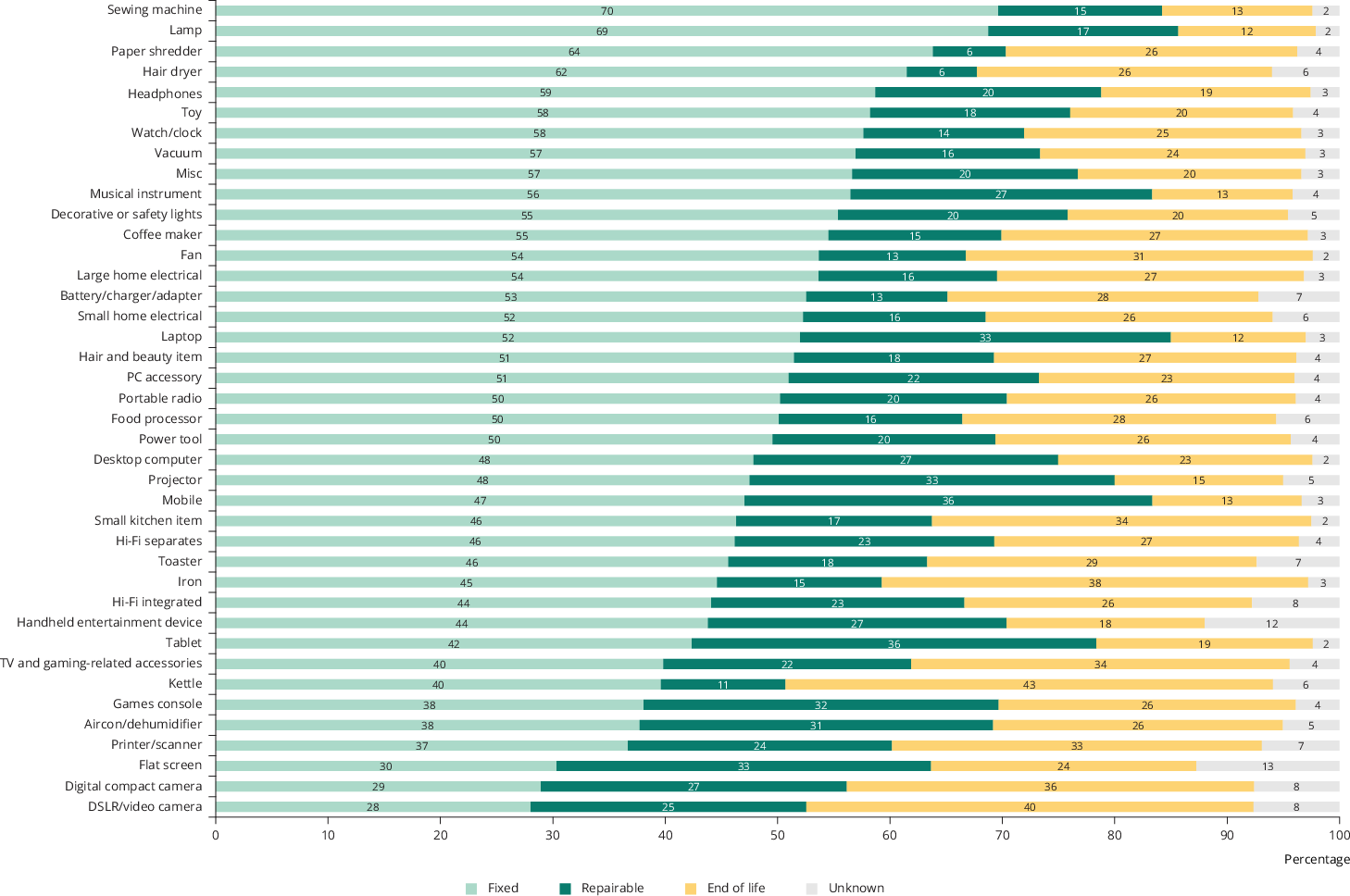

Another repair data source is the alliance of ‘repair cafes’ where people meet and support each other in repairing different products. These alliances register the types of products repaired (but not whether it is successful), age of products, common failures, etc. They therefore form a rich database to inform the development of more product-specific legislation (access to spare parts, etc.). Although the data are available in a limited number of countries only, repair cafes still represent a good source of product-specific information (see Figure 6).

More info...

Conclusion

The ongoing digitalisation of many processes in our society has generated new data streams that facilitate monitoring of these processes, often at product level. While this can be an attractive alternative to more traditional (and often expensive) data collection, none of the case studies presented here is perfect. But they do represent examples of relevant sources of complementary data that can, in many cases, be used to develop novel proxy indicators to increase the granularity of monitoring.

In other cases, data are collected to support market or regulatory processes. The key challenge here is that the processes may not be uniform across the EU and thus data may be representative of only one or a few Member States. There are, however, increasing opportunities to use novel sources of data to contribute to better monitoring the EU’s transition to a more circular economy.

Identifiers

Briefing no. 23/2021

Title: Monitoring the circular economy using emerging data streams

EN HTML: TH-AM-21-023-EN-Q - ISBN: 978-92-9480-426-6 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/714610

EN PDF: TH-AM-21-023-EN-N - ISBN: 978-92-9480-427-3 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/457940

Document Actions

Share with others