This briefing builds to a large extent on the municipal waste management country profiles, developed in close cooperation with the authorities of the Western Balkan countries. The project was funded by the EU’s Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA II).

Municipal waste: facts and figures

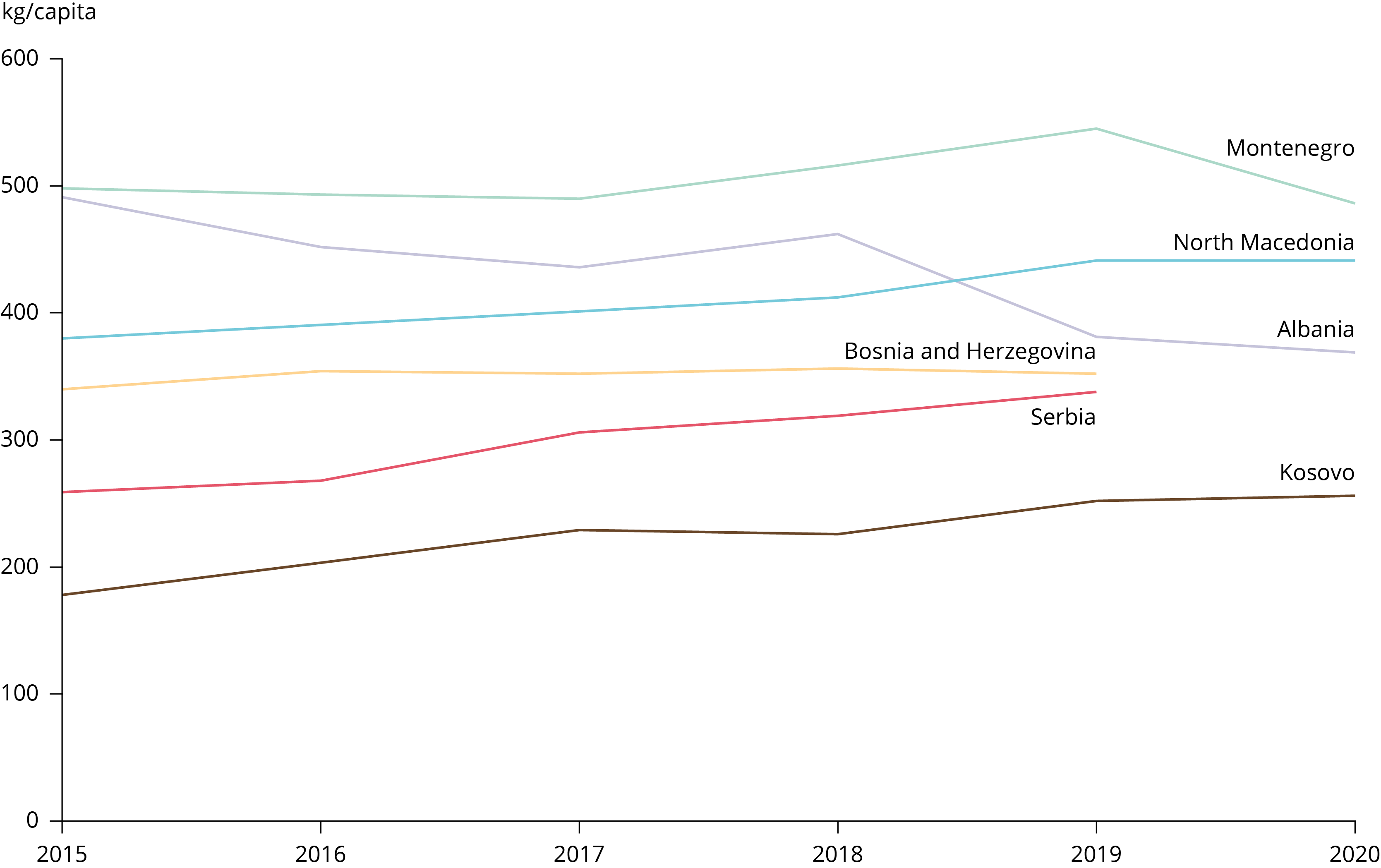

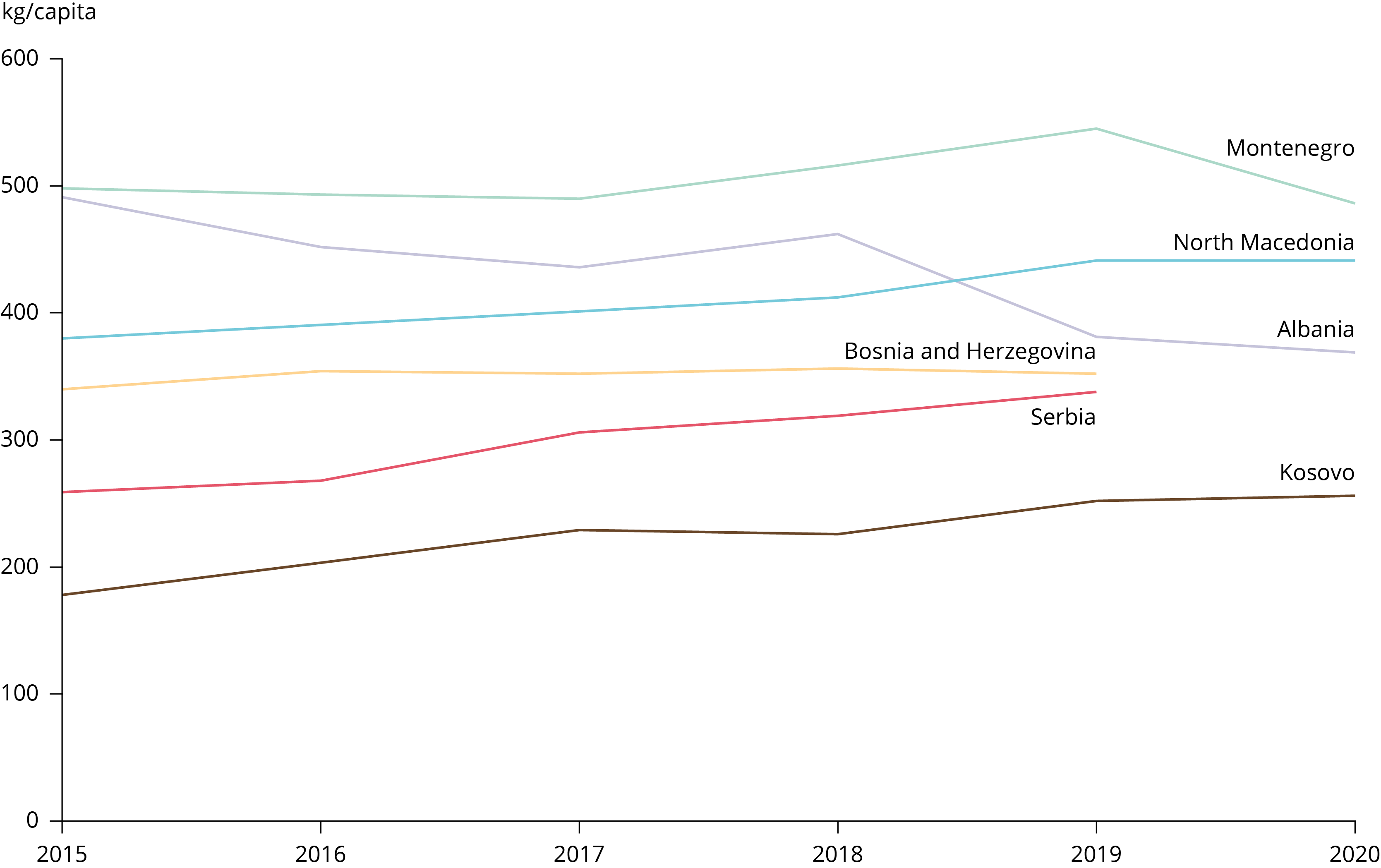

Since 2015, municipal waste generation per capita has increased in Kosovo (under UN Security Council Resolution 1244/99), North Macedonia and Serbia, remained rather stable in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Montenegro, and decreased in Albania (where the decreasing trend is the result of improving data quality rather than decreasing waste generation) (Figure 1). These countries demonstrate different levels of municipal waste generation, ranging from approximately 250kg/capita in Kosovo to almost 500kg/capita in Montenegro. These values are all less than the 2020 EU average of 505kg/capita and correspond to below-EU-average household expenditures in the Western Balkan countries.

Notes: Data for Montenegro (2015-2020), North Macedonia (2020) and Albania (2015-2017) are flagged as estimates. The 2016 data for Kosovo, and 2016 and 2017 data for North Macedonia are interpolated.

Source: Eurostat (2022).

More info...

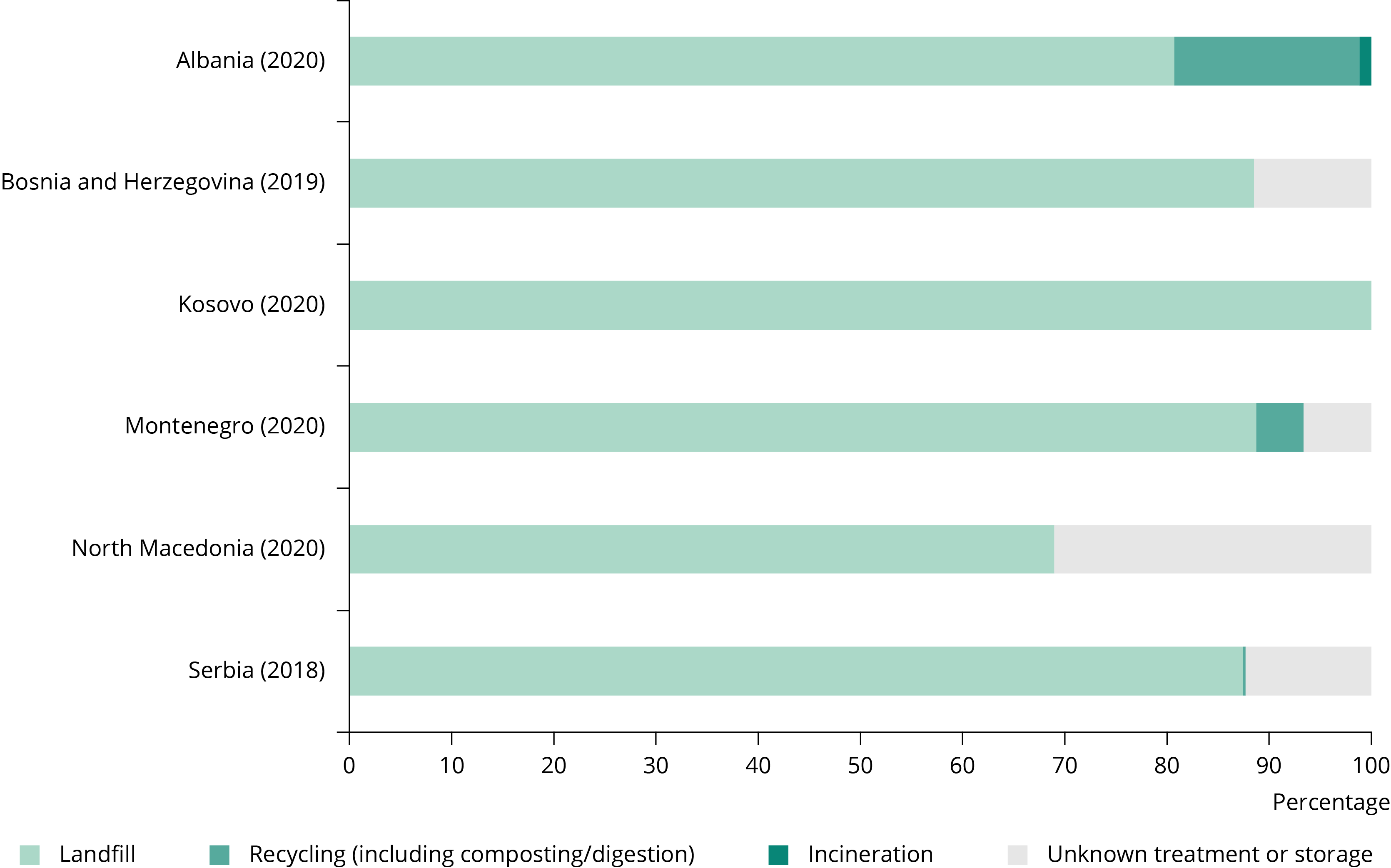

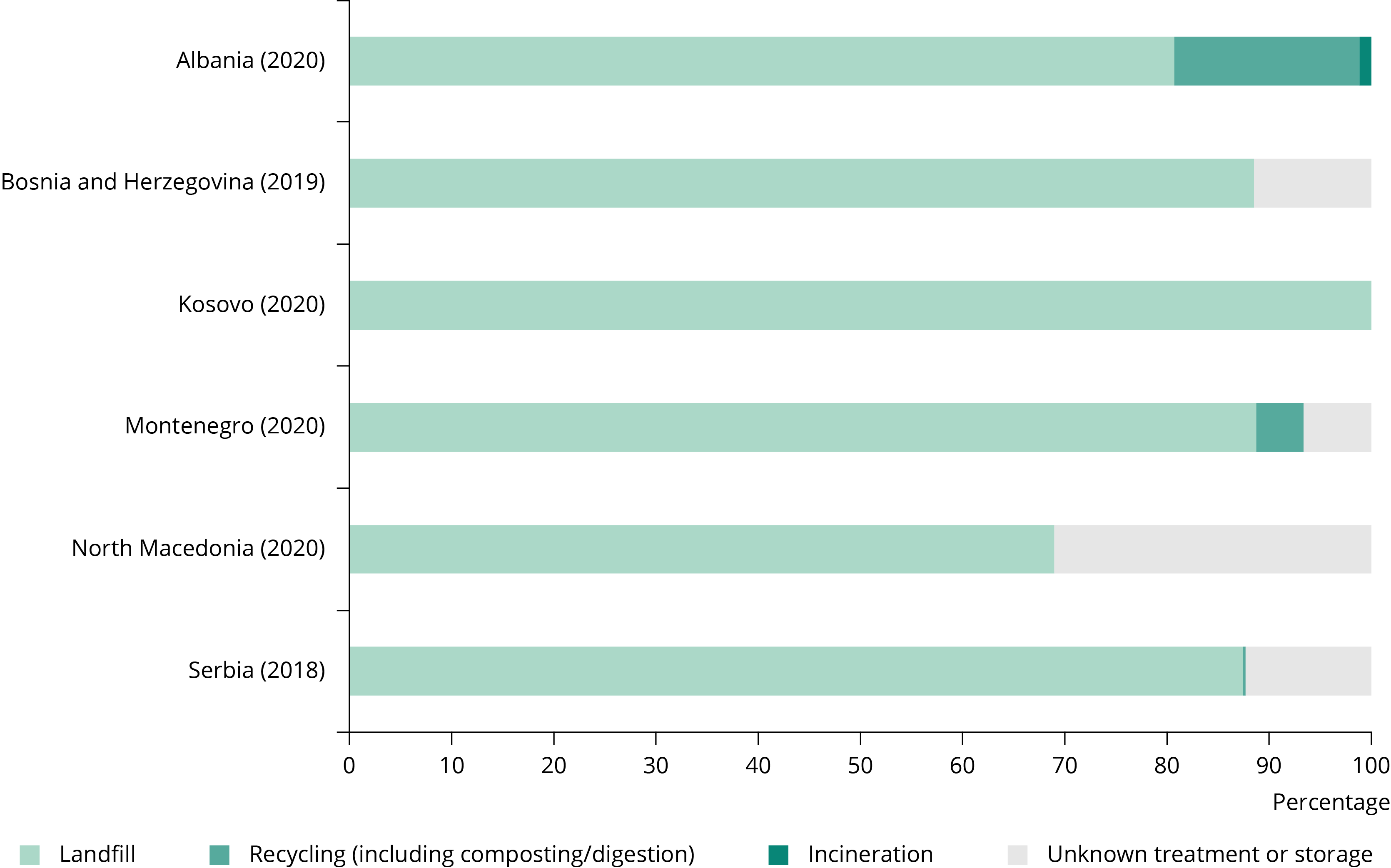

All Western Balkan countries still rely heavily on landfilling: considerable amounts of waste end up at illegal dumpsites and recycling is mostly still negligible, with little progress being made over the years (Figure 2). Albania’s data include estimates for recycling through the informal sector.

Notes: Because of data availability, data for Bosnia and Herzegovina refer to 2019 and for Serbia to 2018. The unknown treatment or storage category is calculated as the difference between generated and treated waste.

Source: Eurostat (2022).

More info...

Good-quality data are crucial to facilitating waste management planning and investments in required infrastructure. However, the availability and reliability of waste data are suboptimal in the region. In many cases, the amounts of waste generated are still high-level estimates, based on, for example, the number of residents in a municipality. Statistical surveys are conducted, but the accuracy and response rates are often low. Many landfills still lack weighing equipment, meaning that data on the treated amounts of waste sent to these landfills are also uncertain. For example, a weighing campaign in Albania revealed that estimated amounts of waste delivered to non-sanitary landfills were considerably higher than weighed amounts (Shapo and Glanxhi, 2021).

However, data quality is gradually improving, for example through the installation of weighing bridges (Albania), the development and implementation of a waste management information system (Bosnia and Herzegovina), the improvement of the response rate of the annual statistical surveys by conducting interviews (Montenegro). The introduction of electronic systems to collect data in Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia will also contribute to improve data quality.

Legal frameworks, strategies and targets

All Western Balkan countries have adopted legal frameworks for municipal waste management, by approximating or being inspired by EU waste legislation, and the EU Waste Framework Directive in particular. However, for most Western Balkan countries, further alignment and harmonisation with this directive is needed. Implementing the legal frameworks is challenging because of a lack of staff, insufficient cross-institutional cooperation, budget deficiencies and poor enforcement mechanisms.

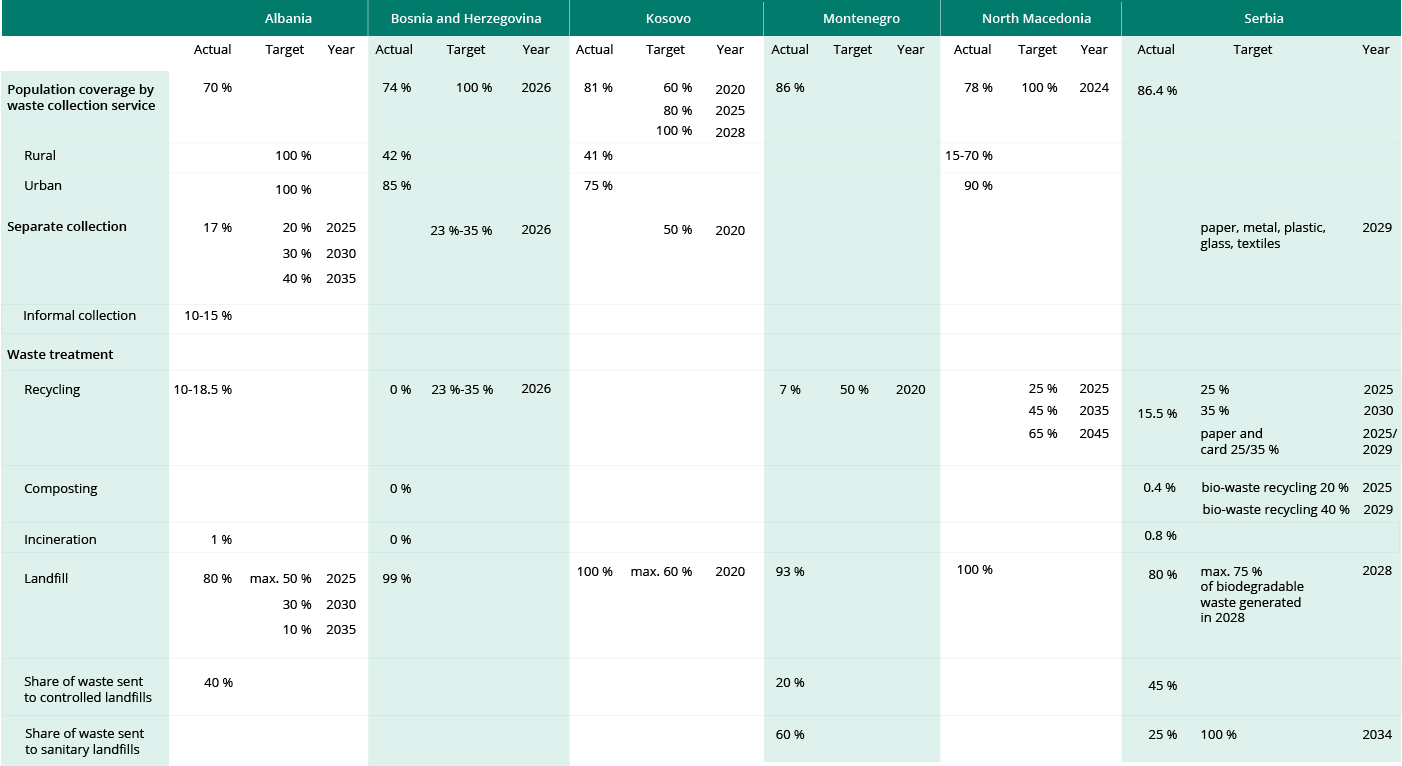

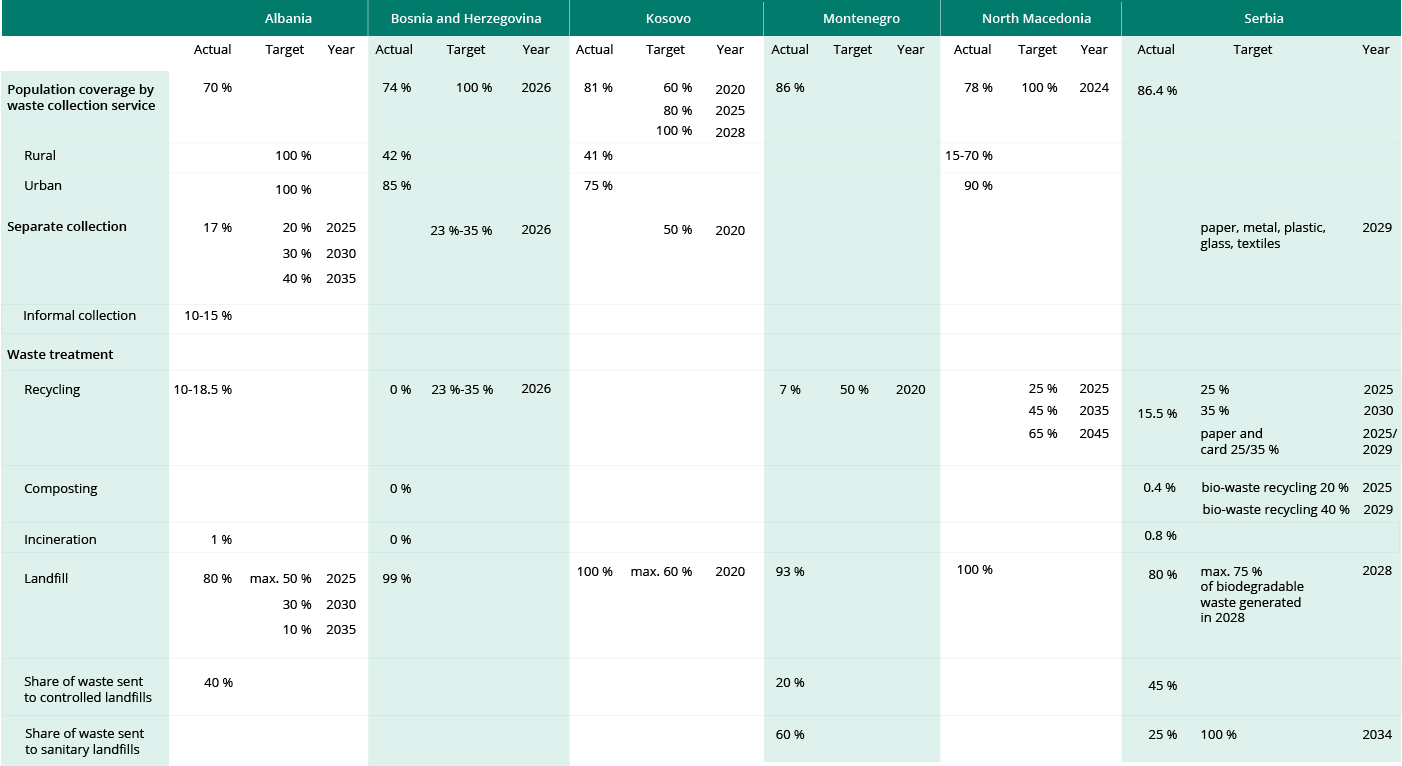

Targets for municipal waste, mainly for recycling but also for collection and reducing landfilling, are set in national waste legislation, strategies and programmes. Countries in the region generally strive to approximate their waste targets with those set by the EU. In some cases, this results in targets that appear ambitious compared with the current situation and the capacity for change. The measures implemented with the aim of reaching the targets are generally weak, especially for recycling targets. Moreover, the lack of data of sufficient quality hinders the tracking of progress towards meeting targets. Table 1 gives an overview of the different targets and the actual performance of the Western Balkan countries.

Note: Informal collection refers to individuals, groups or micro enterprises collecting waste but not in a way that is recognised by the authorities as being part of the waste management system (adapted from Scheinberg, 2011). ‘Actual’ data refer to 2019/2020 (for Serbia not yet available in Eurostat’s database).

Source: EEA (2021) and updated information provided to the EEA in 2022 by the Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina (personal communication, 9 February 2022) and the Serbian Environmental Protection Agency (personal communication, 24 February 2022).

Waste management funding

If the polluter-pays principle is applied, service fees or tariffs should represent the main revenue for municipal waste collection and treatment. However, in the Western Balkan countries, fees do not usually fully cover the costs of collection and treatment. Moreover, fees are often fixed per household or calculated based on the living area, and thus incentivise neither waste prevention nor separate collection for recycling.

Many legal landfills do not apply gate fees (e.g. in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo) or the gate fees applied cover only the costs of very basic operations (e.g. in Kosovo, Serbia). In Montenegro, gate fees are the same for mixed and separately collected waste, so there are no incentives for waste collectors to collect recyclables separately. In addition, given the high number of ‘zero-cost’ illegal dumpsites and low-cost, substandard landfills in the region, many municipalities and waste collectors avoid official treatment options to evade the payment of fees. This harms the smooth operation of the few sanitary landfills and results in more environmental pollution. Although enforcement and subsequent fines are in place in most countries, they are seldom imposed because of a lack of resources.

As a result of insufficient fees and diversion to illegal options, waste management operations lack financial viability and additional public funds are needed. However, funding remains too low for sufficient improvements in waste management. The region would benefit from a fee structure that addresses these issues coupled with more effective enforcement.

Collection coverage and separate collection

The share of the population served by public waste collection ranges from 70% (Albania) to 86% (Montenegro and Serbia) and has slightly increased in all countries over the past few years. It is largely rural areas that are not covered by public waste collections. The main challenges are a lack of infrastructure, e.g. non-asphalted streets, difficult-to-access areas, streets that are too narrow for collection trucks and operational limitations such as insufficient collection and treatment capacity. Waste that is not collected may be dumped illegally.

The systematic separate collection of recyclables has not been introduced in any of the Western Balkan countries, yet some initiatives have been put in place: Albania, Kosovo and Serbia reported pilot projects to collect some recyclables separately; and, in some municipalities in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro, citizens can take certain recyclable wastes to collection points or civic amenity sites. In North Macedonia and Serbia, producer responsibility organisations have collection points for packaging waste, but these are uncommon.

The informal sector plays an important role in all Western Balkan countries, especially by collecting recyclables with high value. These are usually collected from waste containers and bins before being officially collected, or they are picked at landfills.

While all countries with the exception of Serbia have defined targets for separate collection or recycling (Table 1), concrete implementation measures are lacking. For example, in Kosovo and Montenegro, the focus is on investing in the sorting of mixed municipal waste rather than separate collection; North Macedonia expects that targets will be attained through the recycling of packaging waste organised by producer responsibility organisations. Bio-waste is not yet targeted systematically for separate collection, beyond pilot projects and some initiatives to promote home composting, even though it represents 26-58% of all municipal waste in the Western Balkans (EEA, 2020) and is a key source of greenhouse gas emissions from landfills.

Extended producer responsibility schemes

One option to improve waste management is to introduce extended producer responsibility (EPR) systems, as they create opportunities for additional funding for the separate collection of end-of-life products and their proper management through the polluter-pays principle.

EPR systems for packaging have been implemented in Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia and Serbia. Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia also have an EPR system in place for waste electrical and electronic equipment, while Kosovo and Montenegro plan to implement such systems in 2022 and 2024, respectively. Albania has started to prepare a draft law creating the basis for an EPR system. This means that all Western Balkan countries have implemented or have plans to (further) implement EPR systems in the near future.

However, to deliver good results, good governance of EPR systems is required. Challenges remain with regard to the effectiveness of the EPR systems currently in place, especially in relation to how fees are defined, collected and used.

Treatment infrastructure

In all Western Balkan countries except for Montenegro, most municipal waste is disposed of in non-sanitary landfills, some of which are operated by municipalities and others are illegal, according to information provided by the countries’ authorities. These sites are often poorly engineered, managed and operated, posing serious threats to human health and the environment. Waste is usually not pre-treated, and, although illegal, the open burning of waste still happens, for example in Albania, Kosovo and North Macedonia.

With the exception of Albania, there are currently no waste incineration plants within the Western Balkans. However, a waste incineration plant is planned to start operation in Serbia at the end of 2022; North Macedonia is planning the construction of a waste-to-energy plant; and preliminary studies are considering this possibility in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Currently, only a small share of waste is recycled. This is mainly waste collected by informal waste pickers who sell it to private companies that prepare it for recycling within the country or for export. Despite initiatives to develop reycling centres and sorting facilities, so far the effectiveness of these has been limited (e.g. in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro).

Waste strategies and waste management plans envisage, among other things, the closing and remediation of dumpsites and illegal landfills, the building of new, more centralised sanitary landfills that meet EU standards, waste transfer stations and sorting plants. Overall, the focus of investment is on the treatment of mixed municipal waste, and it remains to be seen if these plans will be realised. Nevertheless, some investment in infrastructure is under way, for example in a sorting plant and a composting plant in Kosovo; a mechanical-biological treatment plant in North Macedonia; three additional sorting plants in addition to the existing four in Montenegro; and two new waste incineration plants in Albania.

There is an urgent need to introduce and extend separate collection systems and improve recycling infrastructure, and to prevent waste from being disposed of in (illegal) landfills. Cooperation across the region and with regional industries might help to build both an economically viable recycling sector and demand for recyclables, thus creating a regional circular economy.

References

EEA, 2020, Bio-waste in Europe — turning challenges into opportunities, EEA Report No 04/2020, European Environment Agency.

EEA, 2021, ‘Municipal waste management country profiles 2021 — EEA cooperating countries’ (https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/waste/waste-management/municipal-waste-management-country) accessed 6 January 2022.

Eurostat, 2022, ‘Municipal waste by waste management operations [env_wasmun]’ (https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=env_wasmun&lang=en) accessed 1 March 2022.

Scheinberg, A., 2011, Value added: modes of sustainable recycling in the modernisation of waste management systems, thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, Netherlands (https://edepot.wur.nl/179408) accessed 6 January 2022.

Shapo, O. and Glanxhi, A., 2021, ‘Accurate data on municipal waste as basis for policy development and improvement of waste management to citizens — municipal waste data estimation based on weighting at depositing sites’, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and Ministry of Tourism and Environment of Albania.

Identifiers

Briefing no. 06/2022

Title: Municipal waste management in the Western Balkan countries

EN HTML: TH-AM-22-006-EN-Q - ISBN: 978-92-9480-468-6 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/132793

EN PDF: TH-AM-22-006-EN-N - ISBN: 978-92-9480-469-3 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/58266

Document Actions

Share with others