- Urban growth - why does it matter?

- Urban Morphological Zones

- Applying the UMZ concept

- Outlook

Urban growth — why does it matter?

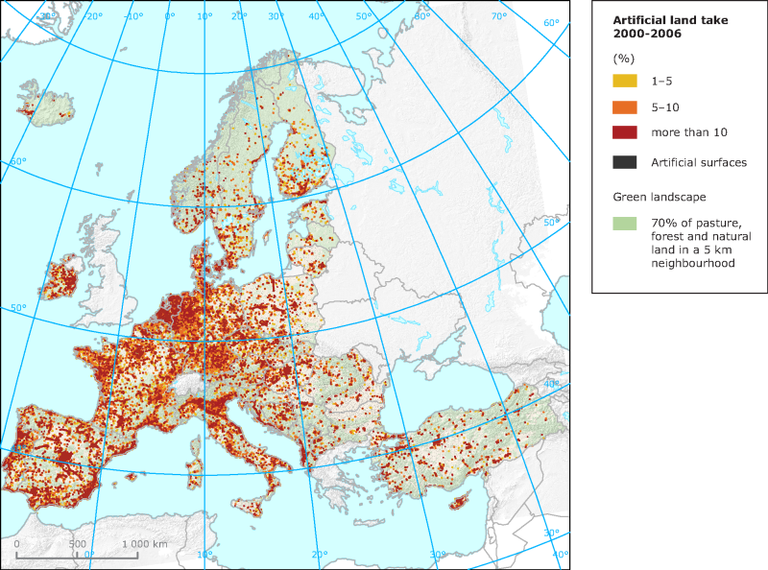

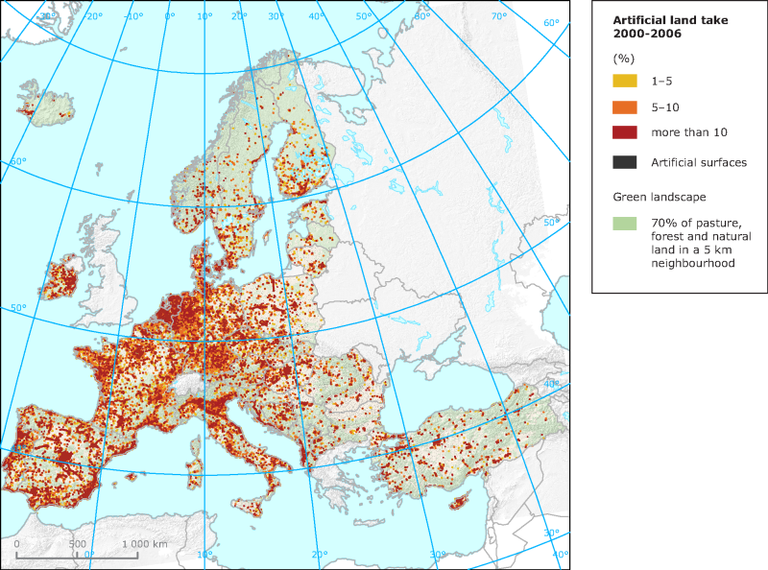

Artificial land cover increased by 3.4 % in Europe between 2000 and 2006 — by far the largest proportional increase in all land use categories. Although artificial cover accounts for just 4 % of the EU's land area, the fact that it is dispersed means that more than a quarter of EU territory is directly affected by urban land use. These results are based on comprehensive surveys for the years 1990-2000-2006 and confirmed by more recent individual studies. Following the results of the PLUREL project (2010), peri-urban (discontinuous) areas grew 4 times faster than continuous urban areas.

By 2020, approximately 80 % of Europeans will be living in urban areas. This expansion, often occurring in a scattered way throughout Europe's countryside, is called urban sprawl.

The extension of urban areas offers benefits, allowing people more living space, single-family houses and gardens. But it can also create negative environmental, social and economic impacts for Europe's cities and countryside, in particular in the case of low density and scattered urban sprawl. These include increasing energy demand, human health problems and declining stocks of natural resources. From a social perspective, urban sprawl exacerbates social and economic divisions.

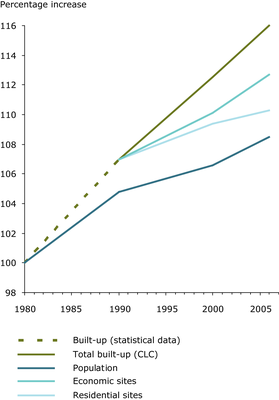

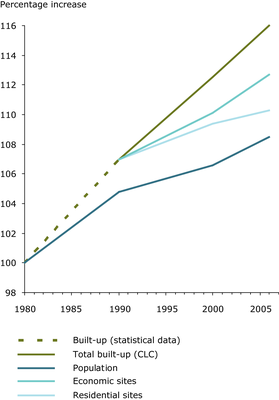

Figure 1: built-up area and population increase in selected countries

Policy challenges at multiple levels

Although urban growth is a local or regional phenomenon, it has impacts far beyond city boundaries. Europe's common market and shared policy framework mean that urban areas are increasingly interconnected. Urban growth therefore raises questions at different levels of governance:

- Where does urban growth occur? Which urban areas have expanded most rapidly in recent times? Was the development compact or sprawled? What trends are expected in coming years?

- What are the drivers behind urban sprawl? Which can be controlled and at what level?

- How sustainable is urbanisation? What are the consequences beyond city boundaries?

- To what extent do European, national and local policies trigger urban sprawl?

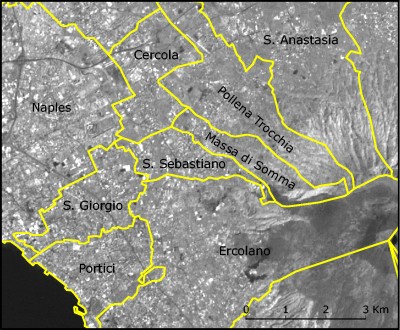

Answering these questions requires an appropriate delineation of urban areas. However, administrative boundaries are often static, seldom reflecting urban morphology and change. And information on urban land cover is very often limited to statistical data confined to these static boundaries.

Map 1: Definitions of urban areas. Southern Italy: administrative boundaries of Naples do not reflect its expansion into numerous surrounding municipalities

How can we measure urban land take?

Satellite images are the primary means of differentiating land cover. Areas of artificial land cover can be analysed to identify urban areas and urbanisation patterns.

Urban areas are very often more continuum than discrete entities, which complicates the delineation of a territorial unit. Nevertheless, some properties of urban areas help define urban boundaries, for example:

- proximity between residential areas;

- population density;

- linear elements that connect people and places, such as rivers and transport infrastructure.

EEA has mapped urban areas across Europe by grouping the CORINE land cover classes that contribute to urban tissue and function. Together, these areas are classified as 'Urban Morphological Zones' (UMZs).

Urban Morphological Zones

UMZs are defined as built-up areas lying less than 200 m apart. They are primarily made up of four CORINE Land Cover classes.

- 'Continuous urban fabric' comprises buildings, roads and artificially surfaced area covering almost all ground; non-linear areas of vegetation and bare soil are exceptional.

- 'Discontinuous urban fabric' comprises buildings, roads and artificially surfaced areas with vegetation and bare soil occupying discontinuous but significant surfaces

- 'Industrial or commercial units' primarily comprise artificial surfaces (concrete, asphalt) devoid of vegetation but also contain buildings and/or vegetated areas.

- 'Green urban areas' are patches of vegetation within urban fabric including parks and cemeteries with vegetation.

In addition, port areas, airports, and sport and leisure facilities are included within UMZs if they are neighbours of the core classes. Road and rail networks and water courses are considered part of a UMZ if they are located within 300 m. Forest and scrub areas belong to the UMZ if they are completely encircled by one or more of the four core classes.

As UMZs are based on CORINE Land Cover databases updated in 1990, 2000 and 2006, changes to UMZs can be calculated between those years.

Data on green urban areas within UMZs, based on Image2000, have also been developed. These data are publicly available from the European Environment Agency.

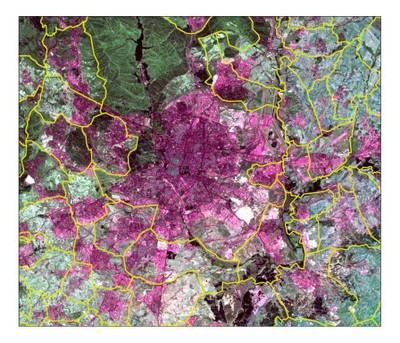

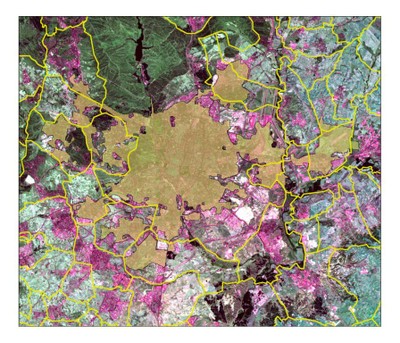

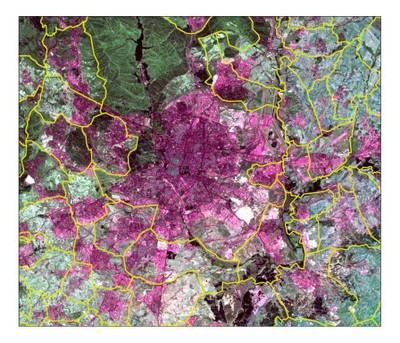

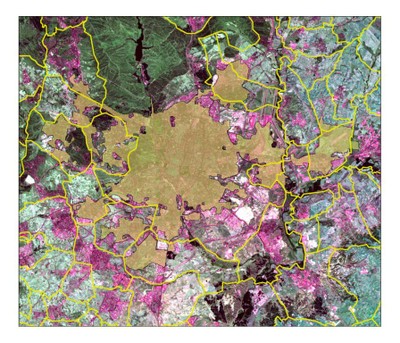

Maps 2 and 3: Metropolitan area of Madrid. Satellite image with administrative boundaries (left) and corresponding Urban Morphological Zone (brown area, right) Source: EEA / ETC LUSI

Applying the UMZ concept

Using the UMZ concept provides much information about the status and trends of Europe’s urban areas, offering answers to many of the questions posed above.

Where are the major urban areas?

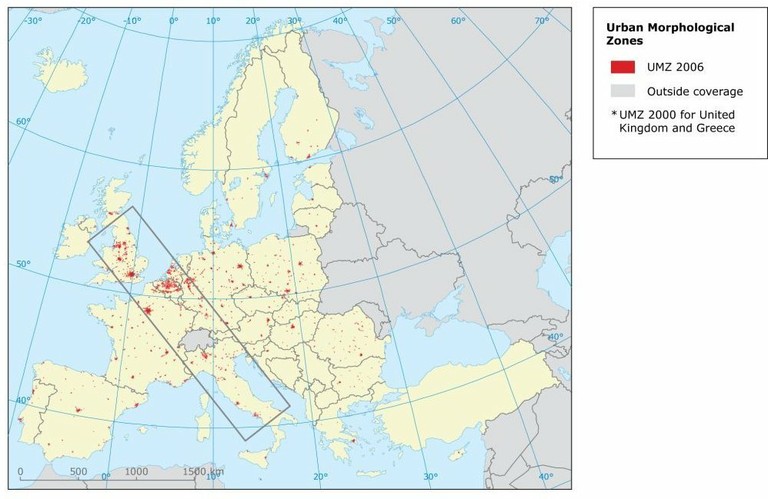

The major concentration of urban areas forms an axis known as the European megalopolis or dorsal running from the UK (London, Birmingham) to northern Italy (Milan, Turin) via northern France (Paris, Lille) Belgium, the Netherlands and western Germany (the Ruhr area, Düsseldorf, Cologne and Bonn).

There are also many cities with more than 50 000 inhabitants in central and eastern Europe (notably capitals such as Berlin, Bucharest, Budapest, Prague, Sofia and Warsaw). Fewer large cities are found in southern Europe, with the biggest being Barcelona, Lisbon, Madrid, Porto and Rome.

Map 4: Urban morphological zones. Source: EEA / ETC LUSI

Where does urban growth happen in Europe?

Map 5 shows that the growth of artificial areas does not only happen around the mayor urban centres but spreads across Europe around smaller cities and towns and also into many rural regions. Thereby population density, on European average, decreases per built up area (figure 1) which points to ongoing tendencies of urban sprawl.

Map 5: Intensity of artificial land take 2000-2006

How are urban areas growing?

UMZs are useful to identify shapes and patterns of urban areas.

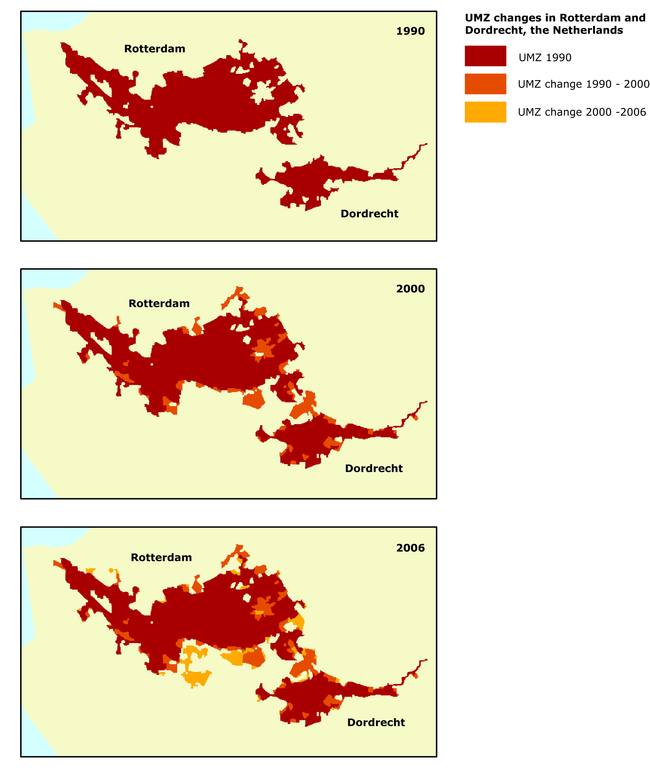

The example of Rotterdam and Dordrecht shows how the two cities became connected through urban growth during the period 1990–2000. About 30 % of Rotterdam's growth was confined to interstitial space of the existing UMZ.

By contrast, during the period 2000–2006 growth shifted to the virgin territory outside Rotterdam, with most of the new urban areas located far beyond the city boundaries of 2000. Most of these new urban areas are below sea level.

Map 6: UMZ changes in Rotterdam and Dordrecht. Source: EEA / ETC LUSI

What drives urban land take?

Generally, drivers of urban sprawl are well known and can be grouped into economic factors (globalisation, European integration, rising living standards, land prices, national policies), demographic factors, housing preferences, social aspects, transportation and regulatory frameworks. All these elements act and interact at different scales and are modulated by local specificities.

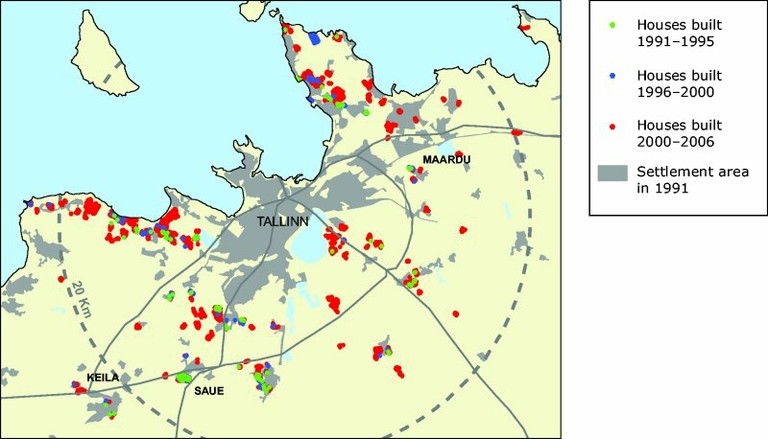

Globalisation and enlargement of the EU are having a strong impact on some new Member States. At the local scale, for example, foreign investments in Tallinn have raised housing prices. This has encouraged locals to sell their apartments and purchase new housing outside the city, fuelling urban sprawl since 2000.

Map 7: New settlements in Tallinn metropolitan area, 2006

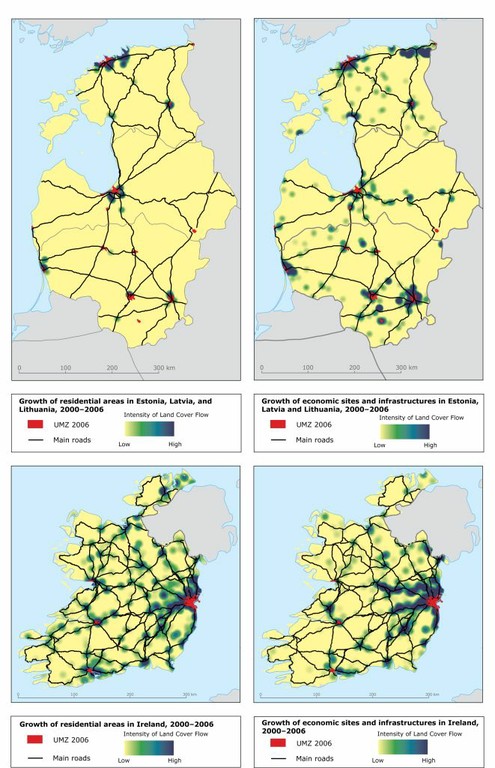

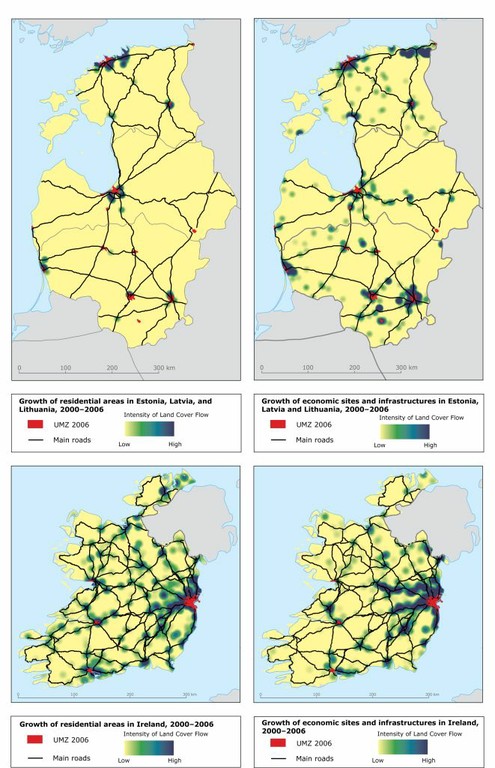

At the regional and national levels, transport networks are an important driver as urban areas grow along communication axes (examples from the Baltic States and Ireland).

Map 8: Intensity of urban sprawl 2000–2006 in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania (above) and Ireland (below)

What are the impacts of urban expansion?

Building new residential and commercial areas, and transport infrastructure consumes different types of resources. Use of land and soil is of special concern because they can be considered non-renewable resources, at least according to human time scales.

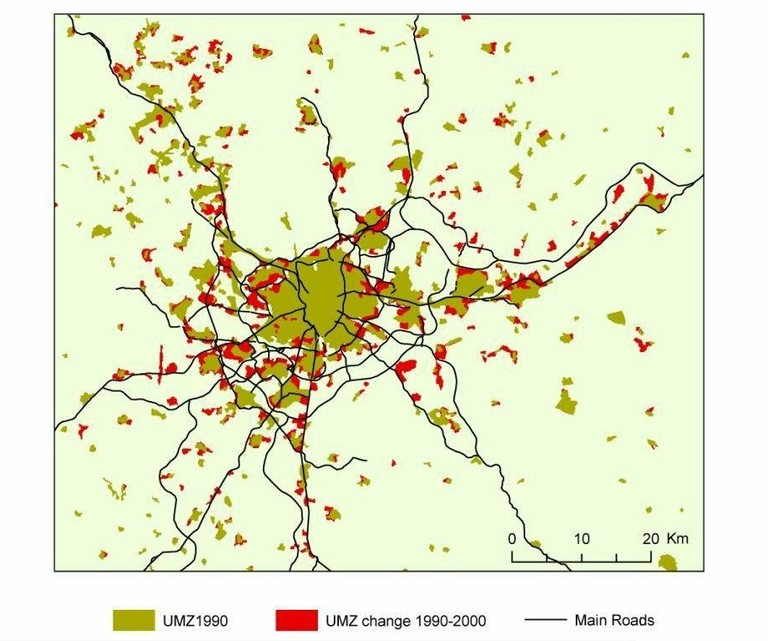

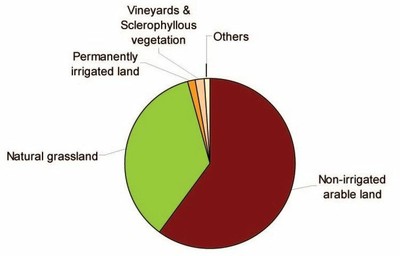

It is possible to identify the land cover lost as a result of new urban developments. At the local scale, for example, most urbanisation in Madrid in recent decades has occurred on former agricultural land, which is typical for urban expansion in Europe. (The second most significant location for urban growth — both in Madrid and across Europe — is natural grasslands.)

Madrid's urban growth took place under a weak spatial planning framework. This resulted in new residential areas far beyond the core city, increasing fragmentation and transport needs. In fact, Madrid is an example of urban sprawl: rapid growth of artificial areas (10 times higher than population growth) and limited brownfield recycling (redevelopment), resulting in decreased population density. Some growth along transport axes extends far from the city centre.

Map 9: Growth of Madrid during the period 1990-2000. Source: EEA / ETC LUSI

Figure 2: previous use of the new artificial areas. Source: EEA / ETC LUSI

Urban pressures on the environment and related impacts have mainly been addressed at the local scale because urban management relies heavily on local planning. However, urban sprawl should also be tackled at the regional scale. It has already been observed at least 20 km outside the UMZ boundaries of several European cities.

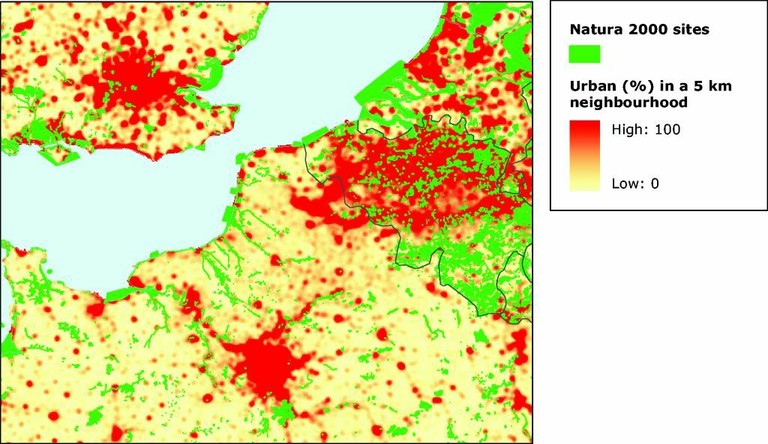

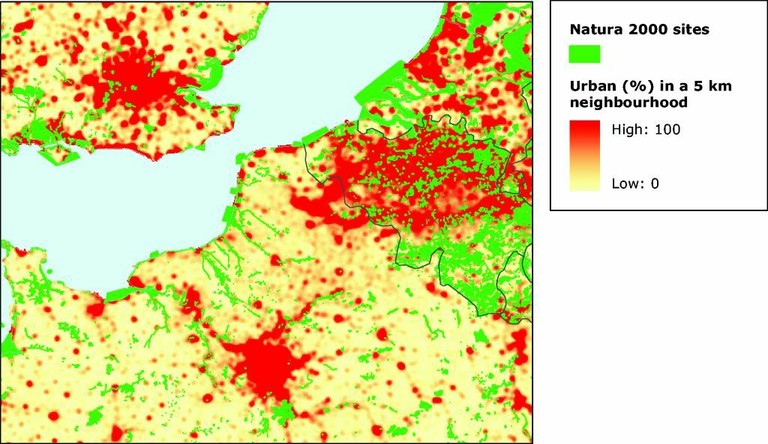

Although urban sprawl has primarily occurred on agricultural sites, considerable impact is now observed on natural areas. Increased proximity and accessibility to natural areas increases exposure to noise and air pollution. In Mediterranean countries, residential areas are getting closer to scrublands and pine forests, resulting in increased risk of forest fires. At the regional and European scales, the pressure of urban areas on Natura 2000 sites can be observed in the example of the English Channel below.

Map 10: Urban pressure on Natura 2000 sites in the coastal areas of the English Channel

What is the intensity of use inside urban areas?

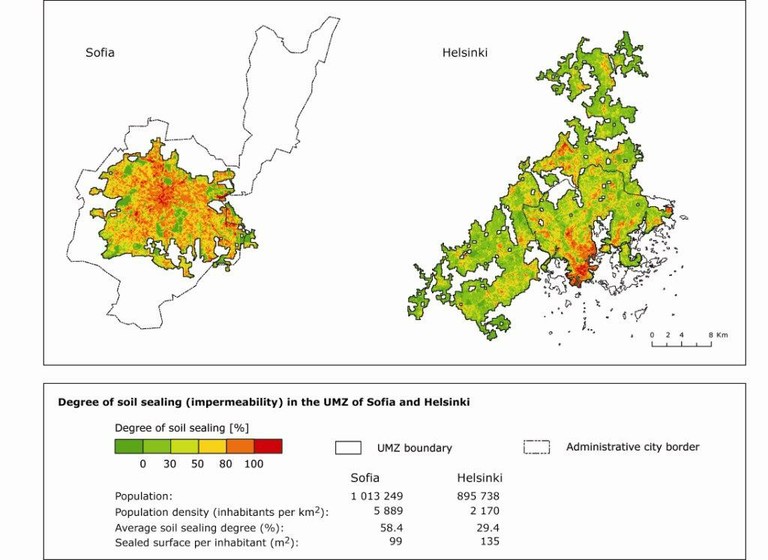

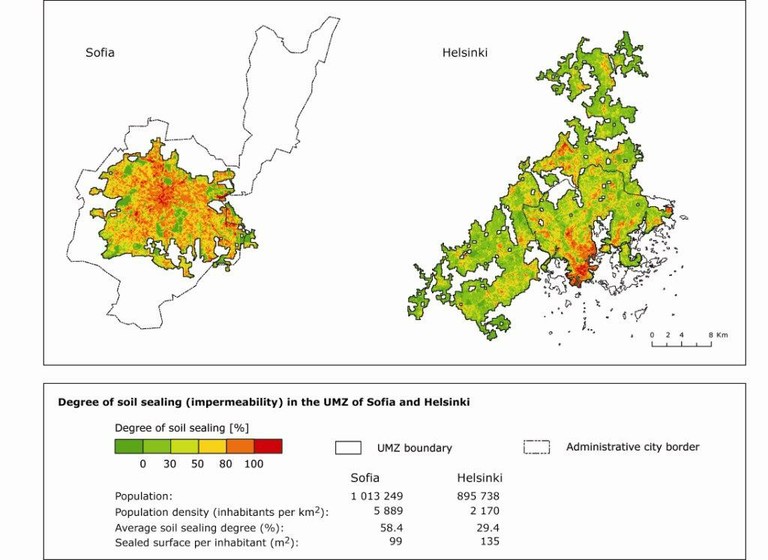

UMZs can vary significantly in their physical features, for example population density and the proportion of land area that is sealed. The varying intensity of uses inside UMZs results in differing environmental impacts.

"Soil sealing" refers to the level of impermeability of the ground. The new European-wide soils sealing layershows impermeabilities between 0 to 100 %. High soil sealing implies very intense urban use, reducing the availability of green areas and biodiversity. It also cuts water infiltration and exacerbates cities' "heat island" effect, as artificial surfaces absorb more solar heat than green areas. Cities with high soil sealing can still have a low level of soil sealing per inhabitant if they are compact and dense. The examples of Helsinki and Sofia with similar population sizes illustrate this point.

Map 10: Degree of soil sealing (impermeability) in the UMZ in Sofia with 1.0 million inhabitants and Helsinki with 0.9 million inhabitants

Outlook

The UMZ approach allows systematic monitoring and assessment of urban growth at different scales across Europe.

Moreover, there are opportunities to analyse urbanisation processes and their impacts (e.g. on water dynamics and floods, quality of life in cities, territorial development and transport efficiency) even more effectively by using UMZ data in combination with new, higher resolution spatial data. Such data include the soil sealing layer and the Urban Atlas — a satellite mapping project under the Global Monitoring of Environment and Security (GMES) service.

The challenge in coming years will be to integrate these data sets effectively, connecting spatial information with statistical data related to administrative boundaries – like the Urban Audit Database -in order to improve our understanding of socio-economic drivers and their effects.

More information:

Document Actions

Share with others