4. AN ALTERNATIVE MODEL

4.1. The role of information in sustainability

Probably, the most widely known definition of sustainability

corresponds to the World Commission on Environment and Development which emphasises the

importance of ensuring the satisfaction of present needs without compromising the ability

of future generations to meet their own ones. Another interpretation, which is based on

the concept of ecosystems and has the advantage that it does not have to answer the tricky

question of what needs are really needed, was stated in the Second World Conservation

Strategy. It specifies that a society is sustainable when: a) it preserves the essential

ecological processes that maintain life and biodiversity; b) it guarantees the sustainable

use of renewable resources and minimises the use of non-renewable ones; c) remains within

its carrying ecological capacity. In systemic terms, sustainability can also be understood

as a hypothetical state in which three subsystems, the social, the economic, and the

biological maximise their own unique set of human-ascribed goals and functions. This

systemic approach emphasises the interacting character of the different facets of human

development and how the failure or omission of one function can negatively affect the

whole system. Finally, in addition to these three well-known definitions of sustainability

there is one of particular interest for the present work. It directly stresses the unique

role of information to achieve sustainability. It comes from ecology and it is based on a

simplified model about the growth of all life forms. From single-cell organisms to animal

forms, life can be thought to depend on the consumption of external resources and on the

information that this organism needs to obtain those resources. Development, then, can be

thought to be a function of only two variables, energy and information. Applying this

model to social development would mean that a move towards sustainability would entail

minimising the use of energy and resources by maximising the use of information and

knowledge.

In the following section, we will centre our argument in a

combination of the last two of the four aforementioned definitions, which seem to be the

most adequate in understanding the role of mass media in the social endeavour of advancing

towards more sustainable futures. Improvements in economic, institutional and ecological

information are indispensable to advance towards sustainability via strategies that allow

the reduction in the need for energy and resources by transforming information into

powerful knowledge, that is to say, going from information for consumption to information

for use.

Therefore, adequate, fast, and accessible communication networks are

essential for the improvement of the environment and sustainability standards. A decisive

way to link information to action is by indicating the means by which markets can improve

their performance simultaneously in relation to their economic, social and ecological

goals. Too often, corporate profits result from the worsening of labour conditions and

environmental standards. Sustainability, however, entails the understanding that the three

types of advances are indivisible, interrelated, and necessary. However, most of the

social actions with permanent incidence in the quality of the environment primarily depend

on the information contained in the monetary price of resources, wastes and pollution.

Under present conditions, natural resources are relatively cheap, many waste products s

have a market value close to zero, and most pollution is unpriced. So cognitive dissonance

appears when media messages and environmental groups denounce pollution or the depletion

of certain resources but at the same time more intensive technologies or new transport

developments allow the relative reduction of prices in this pollution or resources. The

prevalence of short-term market evaluations and priorities on social and environmental

goals impedes integrated sustainable economic decisions.

It is a basic neo-classical economics theory assumption that

negative environmental externalities and costs can be internalised by market functioning,

whenever the interacting parties have enough information about the side effects and costs

of their activities. (However, it is no surprise that many of the assumptions of this

impeccable model are not fulfilled in practice). Whether we believe in this proposition or

not, there are good reasons to think that better information should allow economic agents

located in different places to produce their outputs with a more environmentally sound use

of natural resources, to improve their access to more efficient technologies, and to

implement the latest standards of environmental quality. Thus sharing new information

technologies that would work within companies, consumer organisations, or trade union

could help to spread knowledge about procedures and regulations on eco-labeling,

environmental auditing, or eco-accounting. In some cases, new information technologies

could also diminish the need for daily commuting and by enabling people to work at home

might also reduce pollution. Economic environmental information could also show how to

design projects in which unemployed or disadvantaged sectors could contribute to reduce

economic pressures on the environment and simultaneously create new jobs or new social

integration opportunities. In general, economic environmental information could be

oriented towards showing practical ways in which individuals and corporations can increase

the economic value of their activities -valued in GNP terms - while being socially

beneficial and environmentally sound.

However, it is one thing to acquire a possible set options and

another to choose between them and act on them. Better market information needs to be

complemented with other kinds of information about how people can improve or participate

in existing economic corporations, political institutions, and civic networks, as well as

creating new ones. An integrated approach to environmental information means that

corporations would work with citizens to achieve common sustainability goals while

citizens would be allowed to enter into corporate decisions for the same reason. Much of

the information related to large-scale risk and potential environmental catastrophes is

held under close corporate control. The lack of channels for local citizens and

stakeholders to participate in decisions on the benefits and costs and on the adequate

safety measures for local communities when they enter into potentially dangerous

situations, increases the potential of catastrophe. Being able to participate in the

existing political and economic corporations means understanding the values, interests or

ideologies which people working in these institutions respond to. Appropriate information

-which also promotes motivation in civic participation - is fundamental in this respect.

Public understanding and intervention in corporate risky decisions is essential to avoid

the worst of the outcomes of large-scale potential accidents. Public debate and

accountability should be understood as a basis for the improvement of safety and

sustainability and not as a threat to corporate power.

Institutional and legal environmental information constitutes then,

a type of information as important as the economic one. Most international, national and

regional environmental legislation is little publicised or understood. Without this

information, citizens then, are indirectly deprived of the right to participate in the

improvement of the environment. Many claims of voluntary organisations to improve

sustainability and environmental quality standards need the legal arguments and support to

be properly defended against those who want to impose private interests. In the same

guise, environmental agreements between the public and private companies also need ample

publicity, if they are to extend the potential for broader citizen intervention and

accountability. Better public knowledge of legal liabilities and the means to denounce

environmental damage are also essential to prevent or compensate many current

environmental degradation processes.

In sum, mass sustainability and environmental information should not

only attempt to provide ecological descriptions about how the natural systems work but

also most important, about how the economic, social and political institutions affect

these ecosystems. Sustainability defined in strict economic terms falls short in

describing what levels of environmental quality and what level of economic growth are

socially desirable in distinct locations and who will benefit most by choosing a

particular set of strategies. Showing and sharing information about the actions of a given

industry, the performance of a political party, or how the average household contributes

to the worsening of the environment can be crucial in realising remedial options and

increasing public awareness of the social causes and responsibilities in a given social

context. The possibilities for society to advance to more sustainable futures depend on

its ability to modify its current energy-intensive, unsustainable, and environmentally

harmful social routines and to create new social structures by developing new forms of

integrated actions across the economic, political and cultural spheres. While information

plays a prime role, it is not sufficient per se to advance towards sustainability.

Sustainability and environmental information can become a powerful source of change only

when it can be broadly incorporated into the social contexts and policy processes and, in

this way, influence substantial decisions on the use of natural resources and the quality

of the environment. Given that change is dependent upon the understanding of available

options, once alternatives have been discovered and considered as feasible, new decisions

can be made. New information opens the way to potential change, but only to the extent

that new possible courses of actions are known to be available now or in the near future.

Being aware of the options for present actions is the first stage for change.

4.2. Key elements of mass environmental information

Mass communication on environmental and sustainability issues face

problems of both quantity and quality. In relation to quantity, it is often said that the

demand and the supply are small, and in respect to quality that time constraints and other

structural conditions affect both the production and the reception of this type of

information. In order to define a new and different paradigm of environmental

communication, these problems have to be analysed and alternatives need to be identified

and experimented. The following items put forward some of the keys to a change in the

traditional model of environmental communication.

Quality of environmental information

All attempts to define "good" quality of environmental

information tend to select few characteristics which are understood as the most important

by the producer, the receiver or the analyst of the information. However, different social

groups focus on diverse traits and differing indicators. Contrasts in the perception of

quality of media information about environmental problems arise between reporters,

industrial groups, administrators, scientists and advocacy groups. Official and public

sources tend to find that being precise and reassuring is often a distinctive feature of

good quality while "being alarmist" constitutes a trait of bad quality;

journalists commonly claim that being impartial or well balanced, "serving the

public", aiming for objectivity, or being independent by not taking part in any

specific vested interests, are usual standards of good practice. Nevertheless, most of

these characteristics are ambiguous, interrelated, and dependent upon the definitions of

the terms. Objectivity, for example, can be simply understood as "what scientists

say", instead of "what different sources say, including scientists", a

trait that could also be called impartiality. In the first case, objectivity would be

measured by the number of scientists consulted or the prestige of the institutions where

they work. In the second one, the emphasis would be placed on the deconstruction or

opposition of scientists arguments by other groups such as NGOs. The notion of

objectivity therefore depends on the assumptions about the production of knowledge and the

beliefs and meanings attached to it by the institutions and the professionals who work in

it. Therefore, apart from academic circles and vested interest groups, the majority of

citizens do not generally have enough time or resources to check the scientific

"objectivity" or "truth" of most environmental information.

Faced daily with an infinite and overwhelming flow of information,

people have little choice but to select and interpret the part of the news which has any

relevant meaning to the personal interests and values. Then, they will believe it or not

accordingly. At the level of mass communication, the objectivity of environmental

information cannot be fully verified. At most, the objective content of it can only be

validated by the interaction of different and visible "truth sources" with their

attendant audiences. Each audience and context claims its own legitimate sources of truth

and expresses in a particular language of motives.

Indeed, the adequacy of environmental information can be evaluated

by the degree to which it integrates the diverse points of view at stake, in each social

context by an open procedure. This however entails that previous decisions about what kind

of procedure to adopt for integration are necessary. Environmental communicators, to

incorporate the demands of their audiences, need to be close enough to the public as to

take people's feedback on meanings and information back to the sources. How close and

personal the contact is to the audiences will greatly determine the possibility of

understanding and quality of environmental information.

Not only must communicators be close to their audiences but also to

their sources and, most important, to the news. Some of the important limitations of the

current model of environmental communication relate to space and time distances between

journalists and the news; these time and space constrictions finally result in partial and

fragmented conclusions. To assure quality of environmental information, journalists need

to be close to the event and close to decision-making. This is not always the case and, in

many occasions, journalists have to interpret the facts or the data through the reports of

other actors close to the event.

An alternative model of environmental information exchange needs to

eliminate time and space barriers between suppliers and demanders of information, that is,

between communicators, sources and audiences.

Quantity of environmental information

The environmental problem does not rely on the lack of environmental

information but on the need for channelling it through the appropriate means and

methodologies. In relation to quantity, we should take into account that an increase of

environmental news does not necessarily mean an increase of environmental information.

More space or air time does not mean better or more information or knowledge (although

having more room available for printing, showing, or transmitting news about environmental

issues, does improve the chance for audiences to receive the messages). Therefore,

concerning sustainability and environmental issues, it seems appropriate to think that

people should have sufficient information, supplied through appropriate methodologies,

until they feel that they can provide an opinion and decide about concrete actions on

distant issues such as the level of national co-operation or the willingness to accept

personal costs in global change policies.

Thus, a state of environmental information deficit could be

described in two ways, either in relation to the demands of the actors of a given social

context or in relation to the information, which is lacking for the resolution of a given

environmental problem. In the first case, a deficit appears when the actual demand of

environmental information by social actors is greater that its supply, whatever the reason

this information is asked for. In the second, it means that there exists an unmet need for

information to deal with a specific problem or set of problems. In this case, however, one

should take into account that information is only one of the many elements that are

necessary to manage a problem and that many other social, political, and economic factors

intervene in environmental management. In particular, the amount of information to deal

with a given environmental problem might be sufficient, but the human resources and social

structures necessary to understand and transform this information into practical knowledge

and action might not be enough.

Therefore, systems need to be developed in order to ensure that the

necessary amount of environmental information is effectively channelled, eliminating

through the use of hyper-textual and hyper-medial languages, the space, time and

variability constraints imposed upon information by traditional communication models.

Interactivity and multiplicity

In traditional media practices, the journalist selects "what is

important" from the different pieces of news that he or she handles. Journalism

sustained in "objective news" is based on vertical transmission - and without

discussion on the interpretative key issues of the news - on the part of only one of the

social agents that can react to it, namely the journalists. Audiences remain passive and

defenceless in front of this one-linear communication model, with the journalist, the

single protagonist of the news. This type of journalism is excluding multiplicity as one

of the intrinsic characteristics of the communication model.

Designing a new communication model from telecommunication networks

would entail modifying the function of journalists, by also empowering the rest of the

social agents to participate in the generation and transmission of the news. Through an

interactive process, audiences, sources and information professionals can meet and react

to an event, processing and interpreting reality from their different perspectives.

From consumption to use of environmental information

There is a very important temporal dimension that affects the

distinction between environmental knowledge and environmental information. Time is needed

to transform information into knowledge. Understanding, the basis of knowledge, needs

time. Much of this time is devoted to the actual act of communication, but time is also

needed to reason. Thinking about new ideas and experimenting with them in meaningful ways

is a time consuming activity. New information needs to be verified, understood and

discussed before it can become part of the body of practical knowledge. For environmental

information to become environmental knowledge, individuals or groups have to be able to

integrate and use the former in meaningful ways whenever and wherever they consider it

convenient. In this sense, to enhance the production of social knowledge on environmental

issues and sustainable development, participatory environmental information procedures

should be put in practice.

The next step is that environmental knowledge can become

environmental action. However, for information and knowledge to promote concrete actions,

people need to select them. The selection from the general flow of information and stock

of knowledge might be carried out more efficiently when the purposes of that information

or knowledge, as well as the actors who need it or want it, can be specified. Obviously,

the purposes of knowledge and the reasons for its production and dissemination cannot be

imposed unilaterally upon a plurality of actors and contexts. On the contrary,

participatory procedures need to be developed to improve the definition of the needs, aims

and sources of information and knowledge about sustainability and environmental issues.

Access inequalities and exclusion in the selection of environmental information can also

result in knowledge inequalities, and in turn, this might create wider external negative

effects that affect large populations.

Converting information of consumption into information of use, and

so, of knowledge and action, means developing participatory models of environmental

information exchange.

4.3. The alternative model

The alternative model must be oriented towards social innovation,

that is to say, towards creation of new systems and platforms that produce information of

real value, leading to discussion and actions. Environmental information has to be

supplied so that it can be used. Advancing towards this model means linking information to

options, and contexts to action, as well as involving all the social agents

(communicators, public, and decision-makers) in the generation and transmission processes

of environmental information. These assumptions have led us to define an alternative model

of environmental information exchange as the integration of three basic practices:

- use of the new technological supports;

- a new and different representation of knowledge; and

- a review of the topics put forward for societys consumption.

Use of the new technological supports

The emergence of new data and image transference systems in

immediately usable forms, through user friendly digital supports of low cost, has led to a

gigantic increase in the volume of information, communication and transference of

knowledge that was formerly offered only by traditional media.

New technological innovations open still poorly evaluated but highly

potential possibilities to environmental communication. The jump of traditional media to

the Internet in the form of web sites that project a digital but otherwise faithful

version of their content without elements of innovation, proves that there is still a need

to experiment in other forms of communication that optimise the differential

characteristics of the telematic networks in the benefice of environmental communication.

A new communication model must be conceived and developed through

the use of electronic platforms and systems, and telecommunication networks. Only through

their use can communication adopt the capacities of interactivity, hyper-textuality,

multiplicity and participation of all the social actors, and innovation in the way

information is presented (with the use of all the multimedia and hyper-medial elements

that confer to information the attractiveness required to catch the audiences), that are

indispensable to replace the traditional model that has proven inefficient to change

social behaviours towards sustainability.

Designing a new communication model through the use of

telecommunication networks means rethinking information (its contents), and also

information professionals. Journalists see their functions changed when found in an

environment which is totally different to the passive, one-linear environment of

traditional media. This new professional is not the protagonist of the news anymore. He or

she must mediate a dialogue between the real generators and transmitters of the news: the

different social actors involved that participate in the news from their own and personal

identities and interpretations of reality.

In the new model, communication is found in the form of virtual

communities, newsgroups, electronic information platforms, telematic networks or digital

systems where all the actors of environmental information meet, interact and participate

to generate and transmit information that responds to their needs and induces

action-taking.

A new and different representation of knowledge

In traditional communication practices, lack of integration has led

to misuse of information to generate action and induce decision-making from the part of

society. Those practices failed to represent knowledge so that it could be used for

action-taking towards sustainability. A new sort of environmental communication could

attempt to integrate strategies, efforts, and campaigns, which are now carried out in an

unintegrated manner.

For instance, many present environmental campaigns publicise that

individual actions are crucial to alleviate environmental problems. This strategy,

followed also by public agencies, has been aimed at strengthening the feeling of

individual political competence in environmental matters. It has been assumed that

"environmental empowerment" can be stimulated by public agencies by raising

awareness of personal capacities to have an impact on social outcomes. This has been

particularly noticeable in some areas such as recycling, green consumerism, and urban

transport. However, media campaigns searching for citizens co-operation in public

and private initiatives to abate environmental problems have often not fulfilled original

expectations or have even ended with the opposite results. Many campaigns have been

launched before the necessary institutional and technological arrangements have been

sufficiently set up. Information strategies have not been understood as part of a broader

"environmental policy mix" where different interrelated goals, strategies and

measures should be integrated. Inconsistencies and contradictions between what public

corporations demand from citizens and what they provide to ensure that people's

participation is efficiently channelled are much too frequent. On many occasions, this has

led to public disappointment and distrust and as a consequence, future opportunities for

positive environmental involvement have not been taken advantage of.

Therefore, an alternative communication model should seek to

integrate different strategies from different institutions through interactive, open,

interpersonal, and democratic procedures between producers and consumers of information.

These could help individuals and social groups define and express more closely what

sustainability and environmental information means to them in their own personal contexts.

And given that abstract issues such as "sustainability" would acquire a deeper

meaning in personal experiences, new ideas in relation to remedial and preventive societal

actions might also be more likely to arise.

Low levels of general education and low levels of environmental

education in particular, make environmental issues appear to be distant, complex, or

secondary problems to the interests and wants of the mainly urban populations. The current

environmental illiteracy of large sectors of society keeps the readerships and audiences

of environmental information small and fragmented. In turn, civic participation in

environmental problems remains very low, especially when the intensity and the scale of

the problems at stake is taken into account.

Increasing levels of education could stimulate the demand for

information and a proper diffusion of mass information could result in improvements in

education. Current formal education, however, does not lead automatically to environmental

awareness. Many other cultural and personal factors affect individual interests and the

search for environmental information. Personal experiences and positions in the market

structure influence the attitudes and the cognitive frames in which both the selection and

interpretation of information is carried out.

Besides, even though increasing levels of information can provide a

greater knowledge of new options for action, there is no guarantee that more diffusion of

environmental information will result in more preventative and individual corrective

measures. Quite the opposite can occur. More information can augment one's capability to

escape individually and result in more opportunities "to flee rather than

fight". Efforts must not be oriented towards increasing levels of information, but

towards social innovation, that is, towards development of systems and platforms that

display options for action and demonstrate the existence of opportunities for substantial

change and engagement. It is only through hope and meaning that decisive transformation

can be brought about by large sectors of the population. Raising awareness of the current

global and local environmental situation, indicating possible options and their attendant

benefits and costs, as well as showing the new roles that citizens and scientists can

adopt in the quest for sustainability, constitutes a vast but slow process of

environmental social learning in which integrated communication is crucial.

Therefore environmental messages ought to be transmitted to the

majority of population through easy, accessible and widespread means of communication. The

development of new information technologies confronts this dilemma. There is no doubt that

new information technologies allow an exponential growth in the flow of transmitted

messages world-wide and have an important role in the quest for sustainability.

Citizens will also need to have adequate indicators to learn about

social and environmental change. However, and most important, there is also the need for

participation of citizens in the selection and definition of the most appropriate

indicators to assess sustainability and the quality of the environment. Indicators

proposed by experts might say little to the public and not integrate their views or

possibilities for action. People, by participating more actively in the shaping of

sustainability indicators, might also be more actively engaged in trying to direct them

towards democratically selected goals, which are closer to sustainable paths. Integrators

should aim to involve people in the production, demand and understanding of this kind of

information. By making the public active in the process of production of the content and

the format of indicators, information could be converted into real communication, made

practical knowledge, and be more easily linked to decision and action. Hence participatory

sustainability and environmental information should begin first by opening debates about

what the problems that mostly affect local populations are, defined in their own terms.

Then, it would be a task for integrators to try to link these local definitions and

priorities to global and long-term environmental problems and trends. By doing so, they

could bring the environmental debate on global issues, future generations, and rights of

non-human beings into deliberation at the local and present contexts of action. Fairness

in the selection and effects of environmental information could be improved then if:

(a) the different stages in the process of production, sorting out,

and transmission of information were easily accessible for examination and redefinition by

the community;

(b) people were able to participate in the decisions relating to

what the key issues to be disseminated in each social context should be; and

(c) they could intervene in the procedures which are used to

validate the information provided about the processes of environmental change and the

benefits and costs of the possible courses of action.

In conclusion, a new type of environmental communication platform

could be specifically devoted to gathering, making intelligible, and spreading timely mass

media environmental products in a manner that can transform information and knowledge

about the environment and sustainable development into information and knowledge for the

environment and sustainable development. The move from the cognitive capacity to improve

sustainability to the actual willingness to do so entails not only informative, but also

educational, strategies.

New communication systems should aim to fuse expert and lay

knowledge in different contexts and to understand the assumptions, languages, and the

logical frames of a plurality of social groups and institutions. They ought to integrate

the plurality ideas and expressive strategies of different publics and sources by a

cross-incorporation of formal and non-formal, telematic and open networks. It is only by a

context-oriented social selection and interpretation of environmental information that

knowledge and understanding about these kinds of issues could be shared adequately among

large sectors of society, instead of being relegated to only a technical elite of

environmental specialists and corporations. This would bring sea changes in the way in

which current mass environmental communication is taking place.

A review of the contents offered to society

Integration between environmental information and action will

require that current media products be brought adequately into particular social contexts.

By creating different procedures and conditions based on new assumptions that determine

media information production and consumption, it might also be possible to produce new

contents, relations, and effects on social structures and institutions.

The traditional division of labour and institutions within the

information and educational fields face serious limitations in confronting the current

environmental challenge. Although during the last two decades there has been a notable

further professionalisation of journalists dealing with environmental issues, they rarely

have gone beyond traditional reporting practices and assumptions. Improving the quality of

environmental information entails changes not only of practices but also, above all, of

assumptions. If the process of integration of environmental information into the social

contexts of action is to be pursued, this should bring about radical changes not only in

the current communication theories, but also mostly in the existing mass communication

practices and institutions. Despite a long and still continuing debate on whether the

media can function as mass educators or not, there is little doubt that on the one hand,

present media cannot act as environmental educators, and on the other, current educators

encounter enormous difficulties in informing adequately large sectors of the adult

population about sustainability and environmental issues. New occupations based on new

assumptions and aims are needed. Those reporters who do not believe that the environment

is worsening and that the sustainability of our societies is increasingly facing serious

threats will very likely still be working with old standards. These old kind of reporters,

of course, will not disappear and might even be very successful in their careers. But

their task will make little contribution to the integration of environmental information

with action and to socioecological adaptation. If the public is to understand and be

sensitive to environmental change, it is the task of the appropriate communicators to do

so in the first place.

In short, one of the most important ways the integration of

environmental information could take place could be through the development of new

professions and institutions that would perform - in different ways but at the same time -

the task of journalists, public educators and others in 'environmental social work'. They

should make possible the translation of complex information into intelligible,

discussible, and attractive issues and provide the time and the human and technical

resources, which guarantee a rich evaluative and participatory feedback from the audiences

to each of the original information sources. By proceeding in this way, mass environmental

information might increase its chances of becoming practical knowledge for the environment

and sustainability.

If this translation is achieved, environmental information should

not appear more complex or uncertain than other kinds of information. Complexity and

uncertainty partly depend on individual and social meanings, and in particular, on the

extent in which this information can relate to personal experiences. Among the main

functions of the new environmental workers would be the development of methodologies to

spread environmental information, by combining interpersonal and informal means of

communication with new developments in information technologies. These methodologies and

techniques should aim at the integration of the plurality of environmental information,

understanding, and knowledge in a way, which would be easily accessible and comprehensible

to large sectors of society, and especially to the adult population.

4.4. Some initiatives testing the new communication

model

Several initiatives have emerged that are testing the potentialities

of the new environmental communication model as it has been described in this report. It

is hard for the purposes of this study to choose among the experiences developed at

different levels (and from which we have enough knowledge), but we will describe and

analyse three that seem to fit particularly the expectations and ideas expressed so far.

First, we will describe the Global City Platform, an information

model developed at local level. Second, we will present the basic features of APC

(Association for the Progress of Communications), and mainly its characteristics at

national and regional levels (Ipanex, Pangea). Finally, we will have a look at a world

initiative of environmental communication, the Earth Negotiations Bulletin of IISD

(International Institute of Sustainable Development)

4.4.1. Global City Platform

The Global City Platform (GCP) is an interactive information system

that gathers together data of the reality and the functioning of a municipality in the

environmental, urban, social, economic and agricultural/natural areas, displays them in a

territorial basis, and allows its analysis. GCP is developed by means of a two-year

project that the Centre of Environmental Information Studies carries out with the support

of the LIFE Programme of the European union. The pilot trial and first implementation of

this platform is carried out in the municipality of Manlleu (Osona, Barcelona).

The GCP is based on the latest information technologies (Geographic

Information Systems and Internet) as the support to display information in a suggestive

and innovative way; to facilitate its access, query and analysis; and to stimulate the

participation of different social actors in its elaboration, interpretation and

transmission.

This system seeks to fit organisation and presentation of

environmental information in a new communication model, which is derived in part from the

emergence and use of the electronic networks and the Internet. In this respect, two

versions of the GCP have been developed: an "integral version", which allows

access to all the information available in the system and which was conceived to give

solutions to the needs of municipal managers; and an "Internet version", which

is more oriented to the general public and citizens.

Tools structure and functionality

Integration and organisation of information

The platform feeds from different sources of information: the Town

Council, Public Administration at regional and national levels, private entities, research

centres, social groups, etc. Once the different types of municipal data are selected as

relevant and formats have been homogenised, information is classified in different areas

of knowledge and activity:

- natural milieu;

- urban milieu;

- social reality;

- economic reality;

- environmental variables; and

- the region (contextual information)

Functionality

The Platform allows simultaneous visualisation and query of several

information levels. In the case of geographic information, this means that we can

superimpose different layers of information related to economic, social, environmental,

urban and agricultural aspects of the city, allowing its combined analysis. This displays

a global overview of the municipality, and can even disclose unshown causality.

It is important to emphasise that, in some cases, original

information coming from the source is in non-graphic formatting (databases, photographs,

etc.) related to the territory. The Platform uses this information previously

unexploited - to display information as a map, making it more understandable and

digestible by the user.

Queries to the GCP can be graphic or alpha-numeric. Some analysis,

specially relevant according to sustainable development criteria, have been previously

defined and incorporated to the system as pre-elaborated and directly accessible

information. Equally, the GCP also includes information about legal limits, recommended

threshold levels, etc. that may be used for the diagnosis of the state of the municipality

with regard to certain environmental variables.

Apart from the functions of visualisation, query and analysis of

information, the GCP incorporates several "assistance" functions such as

information updating or search tools.

Applications

(A) Tool for planning and urban management

- Political agents, decision-making actors, and municipal technical

personnel have a system that displays the performance of the city through statistics and

cartography on the economy, the social situation, and the urban and natural environment.

It is a very useful tool for their daily management work, and for the long-term planing.

- Public information system. A new source of information

- Civil society, the media, or experts on the urban system have access

to updated and detailed information for their work and study; this allows them to evaluate

and draw conclusions about the performance of the municipality, and about possible

improvements to be implemented. The system covers different access levels depending on the

type of user (associations, schools, citizens, professionals, etc.) through friendly

interfaces.

(B) A new communication bridge between citizens and local

Administration

The platform enables interchange of information and opinions between

the citizens, the media and the local Administration. It can be used to disseminate

proposals and outcomes of local policies and strategies for the improvement of life

quality among citizens and the interested collectives. On the other hand, the platform

will allow for the collection and channelling of the opinions and proposals of the

citizens and their presentation to policy makers.

(C) Tool for sustainability

- The municipality as an urban system: Approaching urban issues in a

partial way, without taking into account the system as a whole and the side-effects of a

decision on related variables, induces partial and incomplete solutions that can worsen

the problem or even generate new ones. The Platform allows an eco-systemical approach to

the municipality, pooling in one single analysis tool all of all the interrelated

variables that can contribute to a certain urban problem.

- Identification of trends towards sustainability: Incorporation in the

platform of pre-defined analysis of sustainability, adapted to the reality of the

municipality and to the available data, will allow monitoring the evolution of the urban

system towards or against sustainability objectives.

(D) The right to information

The platform, accessible through the Internet, seeks to promote

citizen participation in decision-making processes. Wider social knowledge about the

reality of the municipality will facilitate behavioural and cultural changes towards

sustainability.

Communicative aspects. The new model

Representation of information

Traditional information sources elaborate and disseminate large

amounts of data, reports, studies, etc. that represent "bits" of reality and,

although they may be exhaustive, they are often partial. Some characteristics of the

information and its sources may hinder the "information process" of a journalist

or a citizen: the extensive amount of information available, difficulty or slowness in

accessing some sources, the use of languages or expressions hard to understand, etc.

The GCP intends to give solutions to this problem through an effort

in the way information is treated and represented, by revising, selecting and homogenising

data in order to assure its quality and facilitate its access and interpretation. As a

consequence of the homogenisation of formats, the platform can display simultaneously

different types of information in a single support, providing a context for data and

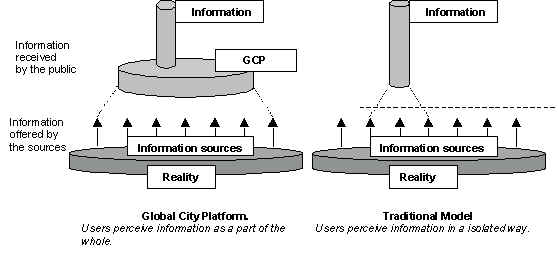

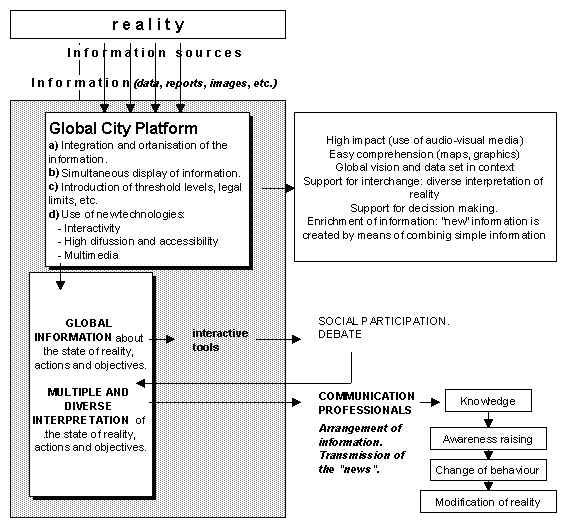

concrete queries (see Figure 18).

FIGURE 18: Setting information in context. The GCP

versus the traditional model

Use of new technological supports

The GCP is based on new technologies: electronic networks,

Geographic Information Systems, multimedia resources, etc. It uses new technologies not

only as support for information, but also as new communication tools endowing the Platform

with qualities such as:

- High impact of the information, mainly due to the use of audio-visual

formats.

- Better comprehensibility of the information. Original information

from the sources, often hard to read and understand, is represented - thanks to the

Geographic Information Systems and computer tools - as maps, graphics, etc., which are

more attractive and understandable.

- Integration of information of different nature (in format - text,

images, sounds - as well as in content) in a single database, allowing simultaneous

displaying, offering global visions and setting information in context.

- Interactivity of the Platform. A mainstay of the communicative

function of the Platform. It offers interactive tools to participate and to express

opinions therefore enriching the information and facilitating decision-making and

behavioural change towards sustainability. These tools (electronic mail, mailing lists,

forums, chats, etc) also allow social actors to provide different interpretations of

reality thus enriching the communicative process.

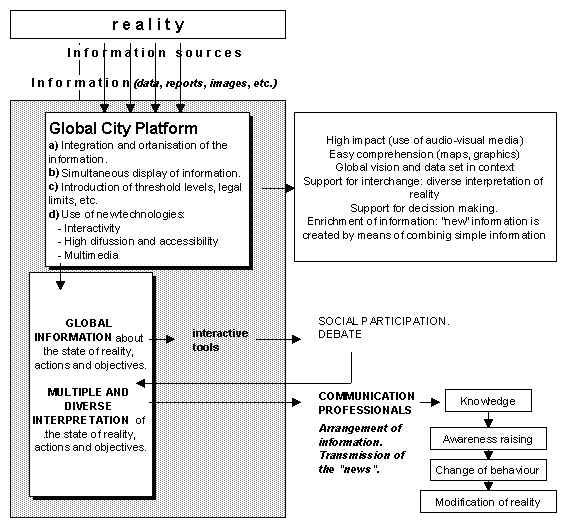

Information for use

As it has previously been said, the PCG is designed to facilitate

comprehension of the information offered and, therefore, its assimilation by the users.

This comprehension of the reality is the first step for awareness

raising and behavioural change from the part of citizens towards sustainability.

The PGC also offers, together with data of the state of the

municipality and its environment, information about legal limits, recommended threshold

levels, etc. that facilitate and stimulate comparison, analysis and design of concrete

actions (Figure 19).

FIGURE 19: The PGC as a complex source of information

4.4.2. Association for the Progress of Communications:

Ipanex, Pangea

The Association for the Progress of Communications (APC) is a global

network, constituted by more than 20 international network members. Its mission is to

provide support to organisations, social and individual initiatives in the use of the

information and communication technologies to achieve sustainable societies.

Between 1982 and 1987, several national independent and non

profit-making computerised networks, appeared as viable information and communication

resources. In 1987, GreenNet (UK) began to collaborate with the Institute for Global

Communications (IGC) that operates with PeaceNet, EcoNet, ConflictNet and LaborNet (United

States). These two networks started sharing their material on electronic conferences, thus

demonstrating that transnational electronic communications can serve communities, both

national and international, in their work towards issues related to the environment, peace

and the human rights.

The process of information exchange succeeded between the IGC and

GreenNet led five networks from different points of the planet to exchange information in

1989. One year later, at the beginning of 1990, these seven networks created the

Association for the Progress of Communications (APC), with the objective of co-ordinating

the operation and development of this global network. From 1997, APC is constituted by 25

network members and exchanges electronic mail and conference services with 40 associated

networks at world level.

This network of computerised global communications for the

environment, the human rights, development and peace, offers communication links to more

than 50.000 non-governmental organisations, activists, educating actors, policy-actors and

community leaders of 133 countries. APC has as principal purpose to develop and to

maintain an information system that allows groups that work in favour of social and

environmental changes, and that are geographically scattered, to co-ordinate activities

on-line at a lower cost in comparison to traditional communication methods such as fax,

telephone or commercial computerised networks. NGOs and activists at world level use the

APC for their internal communication as well as for their efforts of public organisation.

APC uses several network tools such as the World Wide Web,

electronic mail (e-mail), electronic conferences (both private and public), databases, fax

and telex, navigation tools (Internet, Gopher, Telnet, FTP, WAIS), news and information

services, directories or international users. To take advantage of its capacity as a

global net of networks, APC has established four principal functional programs:

- Support to electronic networks. This program is directed to

strengthen the capacity of existing and emerging electronic networks, as well as to build

strategic communities.

- Promotion of strategic uses of computerised communication and

information technologies. This program intends to empower communities to take advantage of

computerised communication and information technologies to get their objectives.

- Development of information and communication contents and tools. The

objective of this functional program is to develop new products, informative resources and

applications to support the development of strategic communities.

- Defence and promotion. Its function is to assure the development of

the political environment to guarantee that computerised communication technologies are

open and equitable, and that access to information is assured on the part of the civil

society, and particularly of strategic communities linked to the objective of social

change.

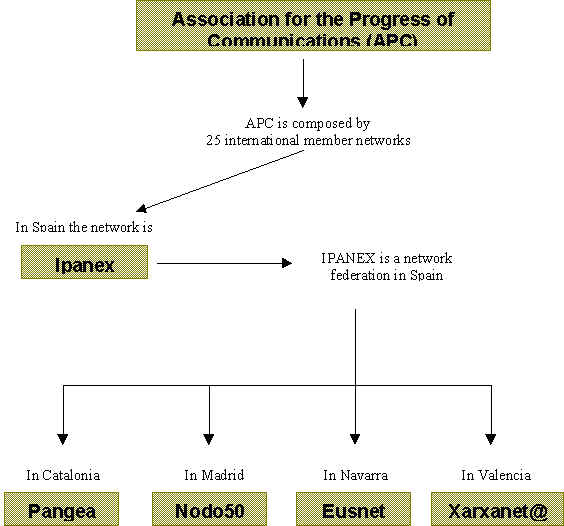

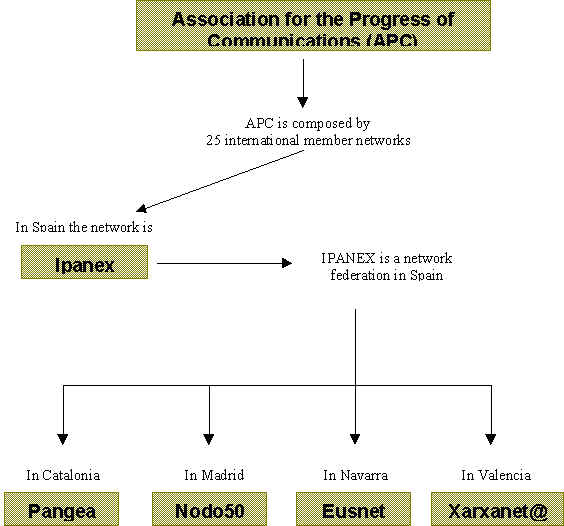

The organisation of APC is represented in Figure 20.

FIGURE 20: Organisation of the Association for the

Progress of Communications

Ipanex is the APC network federation in Spain. This network

integrates four nodes: Pangea (Catalonia), Nodo50 (Madrid), Eusnet (Navarra) and Xarxanet@

(Valencia).

Pangea "Communication for Co-operation" groups NGOs whose

scope of activity is preferably Catalonia, though they can develop part of their action in

other communities of Spain and other countries of the world. Its objective is to promote

the use of telecommunications and data processing between persons and organisations that

work for health, education, peace, co-operation, development and the environment.

Pangea deals mainly with education, women and BCNet, all areas

linked to the use of the Internet. The net is centred in private and public conferences of

Pangea, Ipanex and APC. These conferences are classified by issues such as the

environment, economy, women, human rights, peace, Latin America or Africa. Furthermore, it

offers information on its campaigns and activities, provides different agendas (of

education in Catalonia, peace, development and interculturality), as well as projects and

congresses. Pangea includes also a directory of links to organisations and associations of

the network.

Pangea edits an electronic magazine, "Més enllà", that

intends be a discussion platform on present topics to mobilise NGOs and alternative groups

of the country. Some spaces are strictly devoted to current issues and others are reserved

to the analysis and reflection on social, political and environmental topics that affect

the planet. There is also a place for the different agendas that are offered from Pangea,

a corner reserved to the groups and NGOs, that can be used as a loudspeaker for their

proposals.

A good example of use of the APC global net is the Conference of

Knowledge, that took place in Toronto from June 22 to June 25, 1997. This conference

allowed developing countries and other states to participate in the world economy linked

to knowledge, raising a dialogue at the planetary level and creating a vast participant

echo between the public and the private sectors.

The organisers wanted to assure that the dialogue and the echos that

were created were available not only for those attending the conference, but also for the

countless persons from all around the world that could take good advantage of their

efforts. With this objective, organisers worked co-operatively with an important number of

entities, public as well as private, to organise a conference in real time in the

Internet, parallel to the one that was taking place in Toronto, as well as different

virtual meetings presided by the conference participants and other individuals during the

twelve following months.

One object of these activities, among others, was to encourage

regional discussions on the Internet and to develop the potential of the Internet as a

means of dialogue, of diffusion, and of development of virtual communities.

4.4.3. The Earth Negotiations Bulletin

Another practical case that has been considered of interest for the

purposes of the study is that of the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB) (and other actions

related to it) produced by the International Institute of Sustainable Development (IISD),

as it represents a world wide service of environmental information that uses new

technologies and participatory procedures to spread data about the planets state of

the environment.

The ENB is an independent information service that provides daily

coverage of the negotiations and development undertaken in the environmental arena at

United Nations level.

The Earth Negotiations Bulletin began as the joint initiative of

three individuals from the NGO community, who were participating in the preparations for

the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in 1992. The three

founders created the Earth Summit Bulletin in March 1992. After publishing daily issues

during the five weeks of the Fourth Preparatory Committee meeting for UNCED, the three

raised funds to publish at the Conference in Rio. Following the conclusion of UNCED, the

International Institute for Sustainable Development approached the three founders with an

offer to continue publishing the Earth Summit Bulletin at follow-up negotiations to the

Earth Summit. In November 1992, the Earth Summit Bulletin was renamed the Earth

Negotiations Bulletin.

The ENB provides clear and informative balanced and objective

summaries of the negotiations that take place on environment and development. This service

contributes to the transparency of the international negotiations and supplies real time

information on decision-making related to the environment and development, through the use

of the new and emerging information technologies. It also shows associative actions

between governments and non-governmental organisations, thus facilitating negotiations,

while it disseminates information on governmental, non-governmental and UN activities at

international meetings.

The ENB provides useful information for policy-makers and for all

those interested in contributing to the process of policy-development. Furthermore, it

maintains a constant information flow on policy development in other parallel negotiation

processes.

The Earth Negotiations Bulletin maintains excellent relationships

with the various Secretariats and United Nations agencies responsible for organisation and

planning of the 1998 events to be covered by the bulletin.

The Earth Negotiations Bulletin does not participate in meetings as

a Non-Governmental Organisation or as media. At all sessions where they provide coverage,

they are accredited to participate as Staff or Affiliates of the Secretariat. This ensures

that their team of writers and editors will have unrestricted access to meetings and

delegates. This access is essential to ensure that the information they provide is

"first hand" and unbiased by hearsay. This status is a precondition for the

participation of the Earth Negotiations Bulletin at any negotiation.

The Earth Negotiations Bulletin maintains supportive and

collaborative relationships with the Non-Governmental Community (NGO). NGOs regularly use

the Earth Negotiations Bulletin as a source of information in planning lobbying strategies

and monitoring the statements of governments during UN negotiations. Developing and

developed country NGOs regularly use portions of the Earth Negotiations Bulletin in their

own publications and the Earth Negotiations Bulletin is placed in the NGO computer

networks.

Three different formats are used to publish the ENB:

- a hard copy version, that is distributed in the negotiations and sent

to readers in more than 95 countries;

- an electronic issue, that is included in the international computer

networks and that arrives instantly to millions of users of thousands of computer

networks; and

- a hypertextual issue, which is incorporated in the World Wide Web

Site of the IISD, named Linkages.

The Linkages is designed to be an electronic clearing-house for

information on past and upcoming international meetings related to environment and

development policy. The Linkages WWW project is a unique experiment in international

co-operation through the magic of the Internet. Although physically located in Canada, the

United States, France, Tunisia and, recently, Kenya and Egypt, the Linkages team members,

using various flavours of e-mail, FTP, and late-night IRC chats work together to create,

in the site, a truly virtual and collaborative work environment.

The mission of the International Institute for Sustainable

Development (IIDS) is to promote sustainable development in decision-making at

international level. It contributes with new knowledge, concepts and policy analysis.

Furthermore, it identifies information on the best practices on sustainable development,

demonstrates how to measure their progress, and establishes associations to widen these

messages. The public and the clients of the IIDS are the companies, the governments, the

communities and the individuals interested in sustainable development.

By means of Internet communications, working groups and the

activities developed, the IIDS establishes networks to link the concept of sustainable

development to practice. This is done through several tools and methodologies among which

are:

- the ENB, that offers daily information on the most important

international negotiations on environment and development;

- the IISDNET, that provides general information on sustainable

development; and

- the IISD Products Catalogue, which includes more than 50 books,

monographs, disks and conference documents.

The International Institute for Sustainable Development has a new

reporting service - Sustainable Developments. It expands the services provided by the

Earth Negotiations Bulletin to other meetings, such as conferences, workshops, symposia or

regional meetings that would not be covered by the Bulletin. Sustainable Developments

provides a timely, professional, high-quality reporting service for these meetings and

disseminates the information extensively via the Internet. These initiatives are growing

in scope and number and are providing increasingly important inputs into the policy-making

process, and the outcomes of these important initiatives should be highlighted and made

widely available to all interested parties.

Lately, the ENB has been present at the II Meeting of the

Intergovernmental Forum of Forests (IFF-2) that took place between 24 of August and 4 of

September of 1998 in Geneva. For two weeks, ENB representatives present at the meeting

offered daily coverage of all discussions. Previously, background information had been

prepared and made available. At closure of the meeting, summaries and conclusions were

also prepared and transmitted. By doing so, the ENB agents act both as suppliers and

demanders of environmental information: they participate, evaluate, integrate, and

transmit environmental information. The ENB minimises the space and time gap between

information generation and information transmission.

Document Actions

Share with others