|

Indicator

|

EU indicator past trend

|

Selected objective to be met by 2020

|

Indicative outlook for the EU meeting the selected objective by 2020

|

|

Use of freshwater resources

|

|

Water abstraction should stay below 20 % of available renewable freshwater resources — Roadmap to a resource efficient Europe

|

|

|

While the area in the EU that was affected by water stress decreased, hotspots for water stress conditions are likely to remain given continued pressures such as climate change, increasing population, urbanisation and agriculture.

For further information on the scoreboard methodology please see Box I.3 in the EEA Environmental indicator report 2018

|

The Seventh Environment Action Programme (7th EAP) aims to ensure that, by 2020, water stress — stress on renewable freshwater resources — is prevented or significantly reduced in the EU. Freshwater is an essential component for preserving biodiversity and maintaining other freshwater ecosystem services such as water supply. Freshwater also serves as a vital input to economic activities across Europe, including agriculture, energy, industrial activities and tourism. While freshwater is relatively abundant in the EU, water availability, population and socio-economic activity are unevenly distributed, leading to major differences in water stress levels across the continent. Water stress occurs in several areas of the EU, in particular in the south and in densely populated areas across the EU, because they are confronted with a difficult combination of both a lack of freshwater and a high demand for it. Overall, the EU area affected by water stress decreased over the period 2000-2015. A key reason for this was a decrease in water abstraction as a result of efficiency gains in agriculture, public water supply, and the manufacturing and construction industries. While efficiency gains in water abstraction are likely to continue in the period to 2020, hotspots for water stress conditions are nevertheless likely to remain, given continued pressures such as climate change, increasing population and ongoing urbanisation. It therefore remains uncertain whether or not water stress can be prevented or significantly reduced by 2020 across the EU. It is indeed important that water abstraction respects available renewable resource limits in order to prevent or significantly reduce water stress.

Setting the scene

The 7th EAP aims to ensure that, by 2020, stress on renewable freshwater resources is prevented or significantly reduced in the European Union (EU, 2013). This briefing presents trends in the use of freshwater resources. Freshwater is an input to key economic sectors such as agriculture, energy, industry and tourism, and it is an essential component for preserving biodiversity and maintaining other freshwater ecosystem services such as provisioning water supply. It is therefore important that freshwater use respects the limits of available renewable freshwater resources in order for water stress to be prevented or significantly reduced. The briefing uses the Water Exploitation Index plus (WEI+) to discuss the freshwater use trends. For more information on WEI+, see the ‘About the indicator’ section of this briefing.

Policy targets and progress

The EU’s Roadmap to a Resource Efficient Europe (EC, 2011) includes a milestone for 2020 that ‘water abstraction should stay below 20 % of available renewable freshwater resources’. As quantity and quality of freshwater are closely linked, achieving ‘good’ status under the Water Framework Directive (see Surface waters briefing, AIRS_PO1.9, 2018) also requires ensuring that there is no overexploitation of water resources.

The EU territory affected by water stress decreased over the 2000-2015 period. Over this period, according to the EEA’s own estimates, at river basin district level, the average amount of EU territory affected was 14 % (1) of the total EU territory. The highest values were observed in 2000 (21 %) and in 2015 (20 %). The relatively high percentage of the EU territory affected by water stress in 2015 represents a significant increase from previous years (for instance the territory affected in 2014 was 12 %). The increase in 2015 was mainly because of the extreme conditions in 2015 compared with 2014 (namely lower precipitation and higher actual water evapotranspiration that contributed to fewer available renewable water resources) (EEA, 2018a).

Overall, water stress is driven by two important factors: (1) climate, which controls availability of renewable water resources and seasonality in water supply, and (2) water demand, which is largely driven by population density and related economic activities.

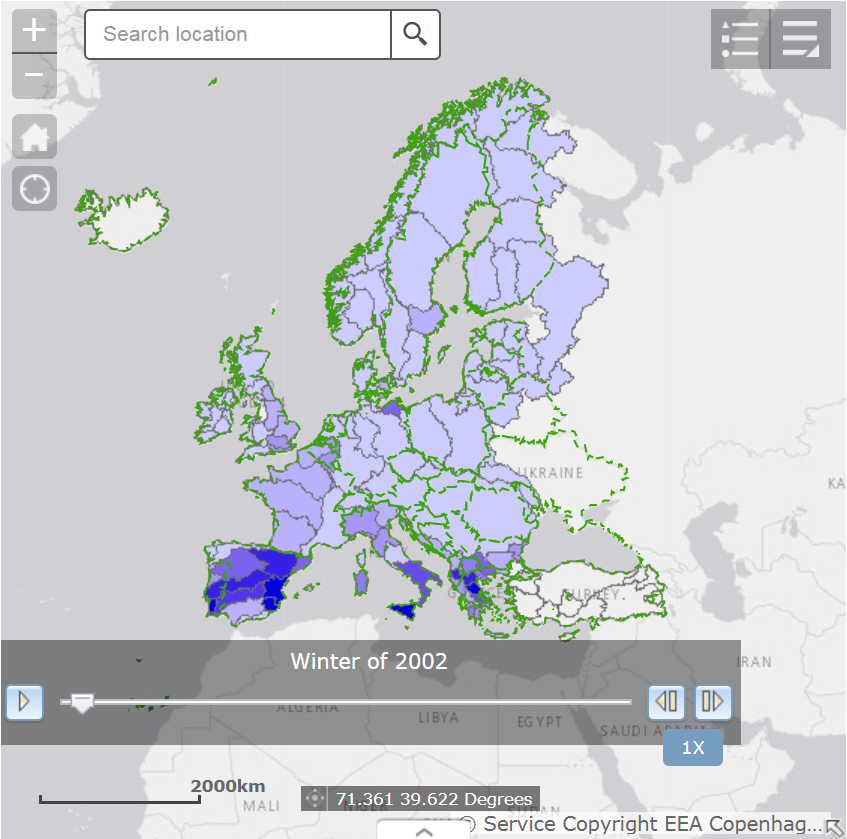

On average, in the EU, freshwater is relatively abundant (EEA, 2015). However, water availability, population and socio-economic activity are unevenly distributed across the EU, leading to major differences in water stress levels within the EU. Except in some northern and sparsely populated areas that possess abundant freshwater resources, water stress occurs in several parts of the EU, in particular in densely populated areas as well as in the southern EU (Mediterranean region) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Water Exploitation Index plus for Europe, 1990 - 2015

Source: a) The European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (E-PRTR), Member States reporting under Article 7 of Regulation (EC) No 166/2006, b) Waterbase - UWWTD: Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive – reported data, c) Waterbase - Water Quantity, d) European catchments and Rivers network system (Ecrins), e) E-OBS gridded data, f) water statistics – Eurostat, f) LISFLOOD, Distributed Water Balance and Flood Simulation Model – JRC, g) OECD water database, h) FAO Aquastat database.

Note: The Water Exploitation Index Plus is presented at river basin district level (including sub basin scale) on seasonal resolution. The reference year is 2015 (Q1: January, February, March; Q2: April, May, June; Q3: July, August, September; Q4: October, November, December). The spatial reference data used when estimating the WEI+ is the ECRINS (European Catchments and Rivers Network System). The ECRINS delineation of sub basin and basin river district differs from those defined by Member States under the Water Framework Directive, particularly for transboundary river basin districts.

Summer is the period when most water stress occurs. This is due to a combination of factors. Water availability decreases because of hotter and drier conditions, while water abstraction substantially increases during the summer compared with winter, because people and sectors, such as agriculture and industry as well tourism that draws from the public water supply, require more freshwater. Around 36 river basin districts, mainly in Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom experienced water stress conditions during the summer months in 2015 (2).

Figure 2 looks in detail at water abstraction by sector. Sectorial demand on water abstraction varies among different regions in the EU. For instance, while agriculture is the main pressure on water resources in southern Europe, water abstraction for electricity cooling is the main pressure in the western Europe.

Note:

- Eastern EU: Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia

- Northern EU: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Sweden, United Kingdom

- Southern EU: Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain

- Western EU: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands

Data show the five main sectors.

According to Figure 2, water abstraction decreased in the EU by approximately 10 % between 2000 and 2015. This was mainly because of efficiency gains in agriculture, public water supply, and the manufacturing and construction industries.

The decrease in water abstraction played a key role in the decrease in the EU territory affected by water stress observed over the period 2000-2015.

Looking towards 2020, while efficiency gains in water abstraction at sector level are likely to continue to improve, hotspots for water stress conditions are likely to remain. These will be primarily in the southern EU as well as in a number of highly densely populated areas of the EU. This is because of ongoing and projected pressures from climate change — such as increasing droughts in several parts of Europe (EEA, 2017a) — increasing population and ongoing urbanisation. It therefore remains uncertain whether or not water stress can be prevented or significantly reduced across the EU. It is indeed important that water abstraction respects available renewable resource limits in order to prevent or significantly reduce water stress.

Outlook beyond 2020

The long-term vision of the 7th EAP is for an innovative economy in which natural resources are managed sustainably. This includes water resources. However, in the coming years, the consequences of various drivers and pressures including climate change, increasing population and continued urbanisation will increase the likelihood of droughts and water scarcity in several regions of Europe (EEA, 2017a). There are many indications that water bodies already under stress are highly susceptible to climate change impacts and that climate change may hinder attempts to restore some water bodies to good status (EEA, 2017a and ETC ICM, 2017).

About the indicator

The water exploitation index plus (WEI+) aims to illustrate pressure on renewable freshwater resources of a defined territory (river basin, sub-basin etc.) in a given period (e.g. seasonal, annual) as a consequence of water use for socio-economic activities. Water use is defined as the water that was abstracted minus the water that was returned back to the environment. The WEI+ shows the percentage of the total available renewable freshwater resources used. A percentage above 20 % implies that a water resource is under stress, while above 40 % indicates severe stress and clearly unsustainable use of the resource (Raskin et al., 1997).

WEI+ data are available at fine spatial (i.e. river basin and sub-basin) and temporal (monthly or seasonal) scales to better capture local and seasonal variation in the pressure on renewable freshwater resources. The indicator focuses on water quantity. For some aspects of freshwater quality, see the Surface waters briefing (AIRS_PO1.9, 2018).

Data on water use have been derived from the following sources: The European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (EEA, 2018b), Waterbase - UWWTD: Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive (EEA, 2017b), Waterbase - Water Quantity (EEA, 2016), Annual freshwater abstraction by source and sector (Eurostat, 2017), OECD water database (OECD, 2018), FAO Aquastat database (FAO, 2017) and National statistical office websites (Eurostat, 2018). The data were integrated into the internal EEA water accounts production database.

For further information on the methodology of the WEI+ see EEA, 2018a and ETC ICM, 2017.

Footnotes and references

(1) The estimates regarding the EU territory affected by water stress that are presented in this briefing are not comparable with the estimates that were presented in the 2017 briefing. The estimates in this briefing correspond to a time period extending from 2000 to 2015 and a geographical scope of EU Member States only. The estimates presented in the 2017 briefing corresponded to a time period of 2002-2014 and a geographical scope that included not only the EU but also Iceland, Norway and Switzerland.

(2) For technical reasons, the 2015 WEI+ for Cyprus could not be calculated. It should be noted, however, that the WEI+ for Cyprus has been very high over the 2000-2014 period pointing to severe water stress.

EC, 2011, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, ‘Roadmap to a Resource Efficient Europe’, section 4.4 (SEC(2011) 1067 final).

EEA, 2015, Hydrological systems and sustainable water management, SOER briefing, European Environment Agency (http://www.eea.europa.eu/soer-2015/europe/hydrological-systems) accessed 5 February August 2018.

EEA, 2016, ‘Waterbase - Water Quantity’ (https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/waterbase-water-quantity-9) accessed 2 May 2018.

EEA, 2017a, Climate change, impacts and vulnerability in Europe 2016 — An indicator based report, EEA Report No 1/2017, European Environment Agency, Copenhagen.

EEA, 2017b, ‘Waterbase - UWWTD: Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive’ (https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/waterbase-uwwtd-urban-waste-water-treatment-directive-5) accessed 2 May 2018.

EEA, 2018a, ‘Use of freshwater resources (CSI 018)’, (https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/use-of-freshwater-resources-2/assessment-3) accessed 15 November 2018.

EEA, 2018b, ‘The European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (EPRT-R)’ (https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/member-states-reporting-art-7-under-the-european-pollutant-release-and-transfer-register-e-prtr-regulation-19) accessed 2 May 2018.

EU, 2013, Decision No 1386/2013/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 November 2013 on a General Union Environment Action Programme to 2020 ‘Living well, within the limits of our planet’, Annex A, paragraph 43(e) (OJ L 354, 28.12.2013, p. 171–200).

European Topic Centre on Inland, Coastal and Marine waters, Zal, N., Bariamis, G., Zachos, A., Baltas, E., Mimikou, M., 2017, Use of Freshwater Resources in Europe — An assessment based on water quantity accounts, ETC/ICM Technical Report 1/2017 (http://icm.eionet.europa.eu/ETC_Reports/UseOfFreshwaterResourcesInEurope_2002-2014/Water_Accounts_Report_2016_final_for_publication.pdf) accessed 5 February 2018.

Eurostat, 2017, ‘Annual freshwater abstraction by source and sector’ (http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=env_wat_abs&lang=en) accessed 2 May 2018.

Eurostat, 2018, ‘National Statistical Offices’ (http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/links) accessed 2 May 2018.

FAO, 2017, ‘Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Aquastat database’ (https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/external/water-use-fao-aquastat) accessed 2 May 2018.

OECD, 2018, ‘OECD water database’ (https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/external/oecd-water-database) accessed 2 May 2018.

Raskin, P., Gleick, P.H., Kirshen, P., Pontius, R.G. Jr and Strzepek, K., 1997, Comprehensive assessment of the freshwater resources of the world, Stockholm Environmental Institute, Stockholm, Sweden. Document prepared for UN Commission for Sustainable Development 5th Session 1997 — Water stress categories are described on pages 27–29.

Briefings

AIRS_PO1.9, 2018, Surface waters, European Environment Agency.

Document Actions

Share with others