1. Which groups are most affected by climate change?

Human-induced climate change causes widespread impacts, including more frequent and intense extreme events (IPCC, 2022). Every year, heatwaves, wildfires, flooding and droughts occur in various locations across Europe. Yet, the impacts of these events on individuals, communities and regions vary, depending on how vulnerable the people or areas affected are, and their level of exposure (IPCC, 2014). For example, older people, children, groups of low socio-economic status and persons with health problems tend to be more vulnerable to climate change impacts than the general population. In addition, people’s ability to avoid or cope with these climate hazards depends on their financial resources, the extent of their social networks, whether or not they own a home, and other factors. A person’s level of exposure is determined by the likelihood of coming into contact with climate hazards, which depends on, for example, whether they live in a flood-prone area or an easily overheated house, or their occupation. Individuals and communities can often be vulnerable in more ways than one and can be exposed to various climate-related hazards. These compounding factors make negative impacts on health and well-being more likely.

Vulnerability of the population in Europe to climate change

Europe is warming faster than the global average and 2020 was the warmest year on record in Europe (EEA, 2021a). Europe is also ageing rapidly. The proportion of people aged 65 years or older in the EU-27 is projected to increase from 20.3% (90.5 million) in 2019 to 31.3% (130.2 million) by 2100 (Eurostat, 2020). Older people are more likely to be adversely affected by heatwaves than the general population (EEA, 2018). They may also face difficulties during extreme weather events such as flooding or wildfires because of lower mobility, or face substantial mental and physical health problems due to, for example, living in a damp home following a flood, or exposure to wildfire smoke (ETC/CCA, 2018).

The health of people with certain diseases (e.g. cardiovascular and respiratory diseases or diabetes) is also affected more by heat than those in the general population, and these people are often at higher risk of heat-related death (EEA, 2018). Pregnant women may be more susceptible to heat stress, and overheating and dehydration may trigger labour (WHO Europe, 2021). Furthermore, mental health illnesses have been found to increase the risk of death and hospital admission related to high temperatures (European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022).

According to Lancet Countdown in Europe, the combination of the increasing number of people over 65 and higher summer temperatures has resulted in an increase in the overall exposure of older people in Europe to heatwaves since 1980 (European Climate and Health Observatory, 2021a). In addition, the European population has steadily become more vulnerable to heat since 1990 because of ageing, urbanisation and disease prevalence (European Climate and Health Observatory, 2021b). While demographic change affects the whole of Europe (EC, 2022a), factors contributing to vulnerability vary. In the north, a high level of urbanisation and a high proportion of people with chronic respiratory diseases make the population more vulnerable; in the south, it is the prevalence of diabetes and kidney diseases; and, in central and eastern Europe, it is cardiovascular diseases (van Daalen et al., forthcoming).

At the other end of the age scale, children, youth and young adults are particularly prone to mental health problems related to climate change (European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022). They tend to be particularly severely affected by the mental trauma associated with flooding or wildfires. In addition, climate anxiety is a big problem for this group, and climate change is one of their biggest causes of concern, often negatively affecting daily functioning and causing them to perceive the future as ‘frightening’ (Hickman et al., 2021).

Socio-economic status also influences the risk of heat-related illnesses and deaths (see EEA, 2018), and financial constraints may make it more difficult for lower income groups to prepare for and recover from extreme weather events (ETC/CCA, 2018). Farmers are also particularly vulnerable, because of the effects of climate change on agricultural production. In particular, if adaptation measures are not taken in southern Europe, the devaluation of farmland could lead to farming being abandoned, with implications for livelihoods and mental well-being (EEA, 2019a). The mental health and livelihoods of traditional and indigenous communities may also be affected by climate change (European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022a). Other factors such as social isolation increase the risk of death caused by extreme weather events, e.g. heatwaves (EEA, 2018), and those with limited knowledge of a country’s official language, including immigrants and asylum seekers, may struggle to understand warnings (ETC/CCA, 2018).

Inequalities in exposure to climate hazards

While all of Europe faces the impacts of climate change, the level of exposure differs widely across regions, depending on location, and economic and social conditions (EC, 2022a). Regions with populations of lower socio-economic status are affected most by high temperatures; for example, parts of Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Italy and Spain are most affected by both long-term unemployment and high temperatures. Moreover, areas with a high number of hot days tend to have populations with a higher proportion of elderly people, for example in Greece, Italy, Portugal and parts of Spain (EEA, 2018).

Lower socio-economic groups tend to live in worse quality housing and may also be unable to afford to mechanically cool their homes (EEA, 2018). Consequently, in nearly all European countries, the lowest income households are less able to keep cool during summer than wealthier households. In Bulgaria, Greece, Italy and Spain, those on the lowest incomes are twice as likely to be uncomfortably hot in their homes than those on the highest incomes (Eurostat, 2012).

In some European countries, local administrative units with higher unemployment rates tend to have larger areas at risk of flooding (European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022b). In addition, approximately 10% of educational facilities and 11% of healthcare facilities across Europe are located in potential flood-prone areas (European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022b). Furthermore, a disproportionate exposure of ethnic minorities, such as Roma communities, to flood risks has been found in some countries (Filčák, 2012). This may indicate that some areas at higher risk of flooding are inhabited by populations either unable or unwilling to move to safer locations. In many cases, the housing market drives lower income groups into areas at higher risk of flooding, as these areas contain cheaper housing (EEA, 2020a).

In many European countries, some of the more vulnerable communities tend to live in dense urban environments and, therefore, may be exposed to higher temperatures due to urban heat island effects (EEA, 2018). In addition, analysis of hospital and school distribution in relation to urban heat islands in 100 European cities found that almost half of hospitals and schools are in areas at least 2°C warmer than the regional average (European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022b). This may pose heightened heat-related risks to school and hospital users and staff.

Those who work in certain occupations are disproportionately exposed to high temperatures, for example those who perform physical work, use protective equipment or clothing, work outdoors exposed to the sun or work indoors with machinery that generates heat (WHO Europe, 2021). Emergency workers, such as firefighters, are particularly likely to be exposed to flooding and wildfires at work, putting them at risk of injury and death (European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022c, d).

2. How can adaptation measures prevent vulnerable groups from being left behind?

As the need for climate adaptation is increasingly recognised and adaptation strategies and plans become implemented across Europe (see EEA, 2020a,b), ensuring that any adaptation measures reduce the impacts of climate change on vulnerable groups is vital. However, adaptation measures rarely benefit everyone in society to the same extent, and, without consideration of equity, new inequalities may arise or existing inequalities may be reaffirmed. Achieving ‘just’ adaptation means shifting the benefits of adaptation measures — and reducing the burdens of adaptation — in favour of the most vulnerable groups (see Box 1).

Climate justice can be understood according to three principles (IPCC, 2022):

- distributive justice, i.e., the allocation of burdens and benefits among individuals, nations and generations

- procedural justice, which refers to who decides and participates in decision-making

- recognition, which refers to respect for, engagement with and fair consideration of diverse cultures and perspectives.

Achieving a climate-resilient society while ‘leaving no one behind’ requires striving towards an equitable distribution of the benefits and burdens of adaptation measures. This means taking into account the existing inequalities to ensure the same opportunities and outcomes for all. Ensuring the equal provision of adaptation measures may not result in the same reduction in risks (see Figure 1). Therefore, actions specifically targeting the more vulnerable or more exposed groups or locations, are justified if they benefit those who are worse off (Ciullo et al., 2020). The meaningful participation of vulnerable groups, or stakeholders representing their interests, in adaptation planning and implementation, and in monitoring the social impacts of adaptation measures, is key to ensuring an equitable adaptation process and equitable outcomes.

Uneven distribution of benefits and burdens of adaptation measures

Currently, the benefits of adaptation measures are unequally distributed across society (ETC/CCA, 2021). For example, across European cities, neighbourhoods with lower socio-economic status tend to have less — and lower quality — green space and thus their inhabitants are likely to be affected more by high temperatures in the summer than those in more affluent neighbourhoods (EEA, 2022).

In many countries, decisions about where to locate flood defences are based on cost-benefit analyses, which usually ignore the distribution of damages across populations (Kind et al., 2019). In traditional cost-benefit analyses, an uneven level of protection is acceptable if a greater benefit to society at large can be achieved (Ciullo et al., 2020), even if more vulnerable populations face disproportionate impacts from flooding (Hudson, 2020). The application of such traditional cost-benefit analyses may disadvantage poorer areas, which calls for the greater integration of social justice into the decision-making process, considering that the risk of floods is projected to increase across large parts of Europe (EC, 2022b).

Flood insurance systems can help to limit overall flood risk by differentiating insurance premiums according to risk level. This can encourage households to move away from — or avoid locating in — high-risk areas. However, high insurance costs in high-risk areas may make insurance unaffordable for the poorest households, potentially resulting in huge flood damages for them. In Europe, only in Belgium, France, Romania and Spain does the public sector cover flood risk through an equitable solidarity-based system. In this system, insurance purchase is mandatory, but premiums are not connected to risk and the government offers support for extreme losses. Currently, flood insurance unaffordability is estimated to be highest in high-risk areas of Poland and Portugal, followed by several regions in Croatia, Germany and the Baltic States. With the changing climate, unaffordability is projected to rise and demand for flood insurance to decline towards 2080, mostly in eastern Europe and some regions in Italy, Portugal and Sweden (Tesselaar et al., 2020). This will disproportionately affect the poorest residents in those areas and calls for transformative solutions in the insurance sector.

Hard defences will not provide protection against flooding for all in the future, and flood proofing of individual properties is increasingly recognised as a cost-effective back-up solution (EC, 2022b). However, flood proofing is expensive and many households are not able or willing to invest in it (Attems et al., 2019). The highest rates of flood proofing unaffordability are found in eastern Europe, the Baltic States and parts of southern Europe. Equitable financing mechanisms and better integration of such solutions into zoning policies and pre-existing welfare systems are needed to ensure that all at risk can benefit from property-level adaptation measures (Hudson, 2020).

Moreover, flood insurance and flood-proofing measures are usually available only to homeowners and not to those who rent private or social housing and who in many European countries belong to the most disadvantaged or vulnerable groups. Tenants may also be unable to benefit from subsidised and incentivised adaptation measures in various European countries and cities, such as the removal of paving from gardens (e.g. in the Netherlands) or the installation of rainwater capturing systems (e.g. in some cities in Czechia, Germany and Poland) (EEA, 2020a). Systemic adaptation solutions for private and social housing are therefore required to ensure equal opportunities for flood protection.

Regulating utility prices as an adaptation measure to reduce demand for electricity or consumption of water (in areas affected by its scarcity) can lead to the unequal distribution of adaptation costs, as the relative economic burden will be greatest for the lowest income groups or vulnerable households (e.g. large families or persons who use additional electricity for medical equipment). Therefore, raising prices without considering the impacts on vulnerable groups may deepen current inequalities. Solutions such as establishing different seasonal tariffs or providing discounts for low water use may be more effective in reducing water use than raising prices (EEA, 2020a).

Developing just adaptation responses in practice

First, the identification of vulnerable communities and individuals is essential for targeting equitable adaptation measures. For example, the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy signatories, when performing their obligatory climate risk and vulnerability assessments, should provide information on the vulnerable population groups that are expected to be most affected by future hazards, to allow adaptation measures to be prioritised (Global Covenant of Mayors, 2018). Spatial mapping of social vulnerability is often used in such assessments (see for example the Climate-ADAPT (2020a) case study of Botkyrka, Sweden). Moreover, in Berlin, the environmental justice index, which considers environmental problems (e.g. exposure to high temperatures) and socio-economic disadvantage, informs the allocation of funding for environmental improvements in neighbourhoods that need them the most (see EEA, 2019b). Community-driven approaches to vulnerability assessments can be used at the village or neighbourhood level to identify who is vulnerable in a bottom-up process (ETC/CCA, 2018).

An example of an adaptation measure implemented in an area identified as vulnerable is the tree planting, construction and restoration of water features, and actions intended to change behaviour during heatwaves, in a residential area of Trnava and Košice, Slovakia, containing housing prone to overheating and a high proportion of older people and children (Climate-ADAPT, 2018). In Paris, the OASIS — ‘openness, adaptation, sensitisation, innovation and social ties’ — programme greens school grounds and makes them accessible to local communities, reducing the risks from heatwaves to vulnerable people. The greening of school playgrounds is also done in Flemish Brabant, Belgium.

To tackle flood risk, the RESILIO project in Amsterdam focuses on fitting smart green-blue roofs, which retain excess stormwater, on social housing apartment blocks (EEA, 2020a). The development of sustainable drainage systems in the relatively deprived Augustenborg neighbourhood in Malmö, Sweden, at risk from surface flooding, shows that adaptation measures can not only reduce climate-related risks, but also deliver socio-economic benefits to the local community (Climate-ADAPT, 2020b).

It is important that adaptation responses are adjusted to the needs of vulnerable groups. For example, early warnings and advice about extreme weather events issued through only mobile phones may not reach those who do not have or cannot use such devices and are at the same time at the highest risk, e.g., the elderly, those with severe mental health conditions (e.g., dementia), the homeless and those in areas with poor mobile network coverage.

This need for specialised or additional support has been recognised in the city of Paris, which holds a register of people vulnerable to heatwaves and encourages the creating of solidarity networks to ensure that neighbours look after each other during hot spells. Similarly, in Bologna, Italy, volunteers and non-governmental organisations assist vulnerable individuals during heatwaves through a payment-free call centre, and look after people at risk, e.g. by accompanying them to cooling centres or hospitals (ETC/CCA, 2018). The region of Kassel in Germany provides a ‘heatwave telephone’, where volunteers call elderly people to warn them about health risks during heatwaves and how to avoid the dangers (Climate-ADAPT, 2017). In Lisbon, the municipality social care department has a contingency plan in place to support homeless people whenever alerts for extreme weather-related events are recorded (EEA, 2020a). In Finland, three non-governmental organisations offer various forms of mental health support for people suffering from climate- and eco-anxiety, targeting particularly vulnerable groups (young people and rural communities) (Climate-ADAPT, 2022).

Engagement of vulnerable groups in adaptation planning and implementation

As the outcomes of planning processes are influenced by who is involved, participation of vulnerable groups is key to ensuring justice in climate change adaptation (ETC/CCA, 2021). EU policies and instruments such as the European Climate Pact and the European Mission on Adaptation (EC, 2021a) place emphasis on higher levels of citizen engagement, and vulnerable groups are already involved in developing national and subnational adaptation strategies in some European countries. For example, in France, the organisational representatives of the most vulnerable populations participated in developing the second national adaptation plan and regional climate policies. In Finland, children, youth, the elderly and the Sami indigenous people were consulted on climate change planning. In Slovenia, municipalities engage with those particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts, as they are required to consult with representative organisations on a wide range of activities from civil protection in natural disasters to elderly care (EEA, forthcoming).

There are also examples of vulnerable groups being involved in making decisions about types of adaptation options and where they should be implemented. In the relatively disadvantaged neighbourhood of Gorbitz in Dresden, Germany, consultation with residents on ways to improve thermal comfort in homes and the neighbourhood, as part of the HeatResilientCity project, led to plans to plant more trees, install window shutters and boost ventilation in apartment blocks (Covenant of Mayors, 2019). Participatory mapping by residents of District 6 in Prague identified that bus shelters were particularly hot and uncomfortable, leading to the installation of green roofs (EEA, 2020a).

Vulnerable groups can also be directly involved in implementing measures. This is the case for many greening initiatives, and the involvement of vulnerable groups in planning and making green spaces has been found to foster a sense of ownership and promote use (EEA, 2022).

3. Embedding justice in adaptation policy and actions from the EU to the local level

Just adaptation in EU policies

The principle of ‘leaving no one behind’ — a central part of the United Nations Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals (UN Sustainable Development Group, 2022) — is a key concept in EU policies and initiatives related to climate change and broader sustainability. The European Green Deal (EC, 2019) emphasises the need for a ‘just transition’ to a society with no net greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, recognising that the disproportionate burden on certain countries and population groups needs to be addressed through specific policies and funding. Action under the European Green Deal will be guided by the European Pillar of Social Rights, to balance economic and environmental policies with social ones.

The EU adaptation strategy introduces the notion of ‘just resilience’, emphasising that the impacts of climate change are not felt equally by all groups and that achieving resilience in a just and fair way is essential for the equitable distribution of climate adaptation benefits (EC, 2021b). Accordingly, the EU mission on adaptation to climate change sets out to accelerate a smart and systemic transformation to climate resilience in a just and fair way, through inclusive governance processes and supporting actions that protect the health and well-being of vulnerable people (EC, 2021a).

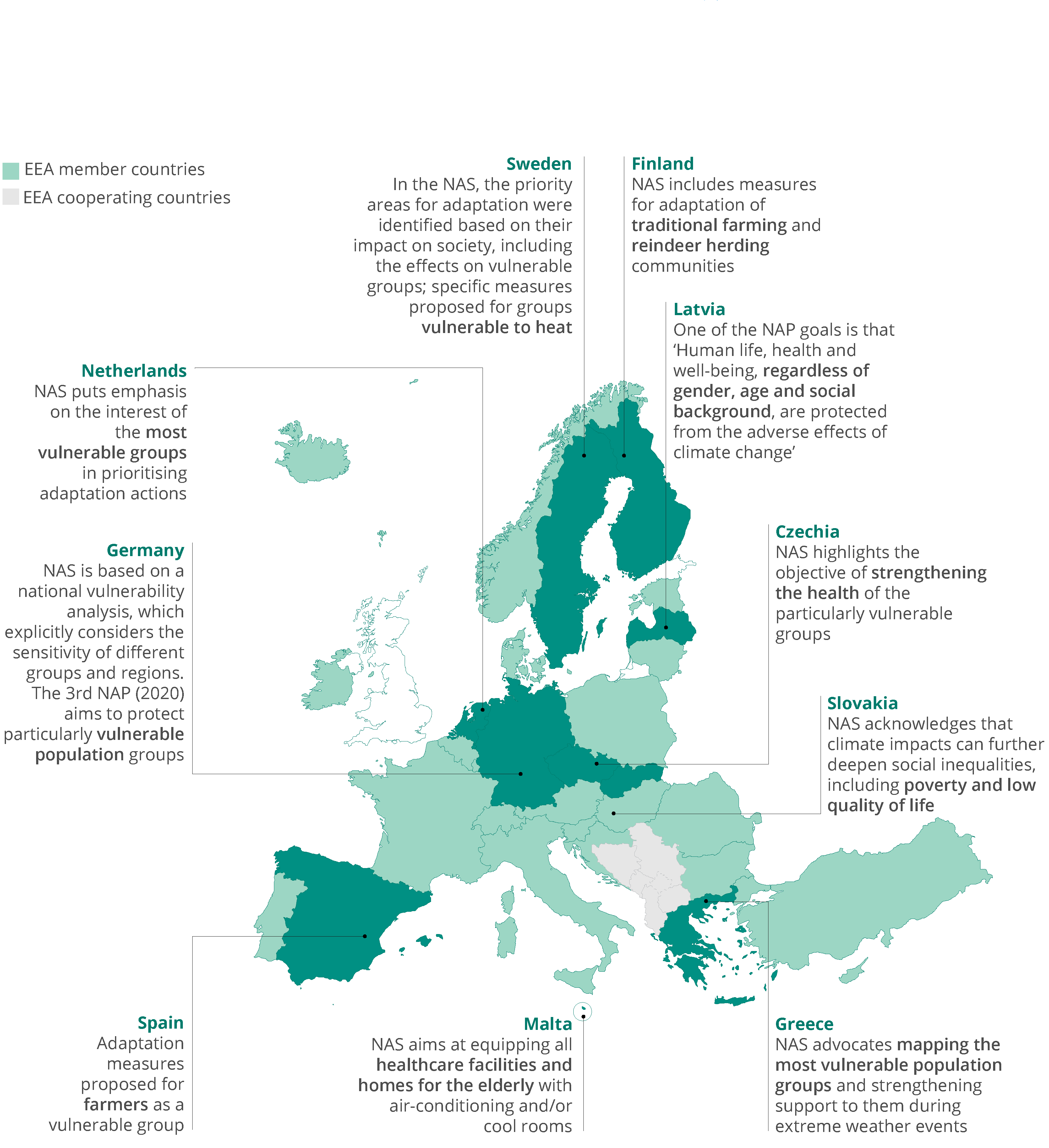

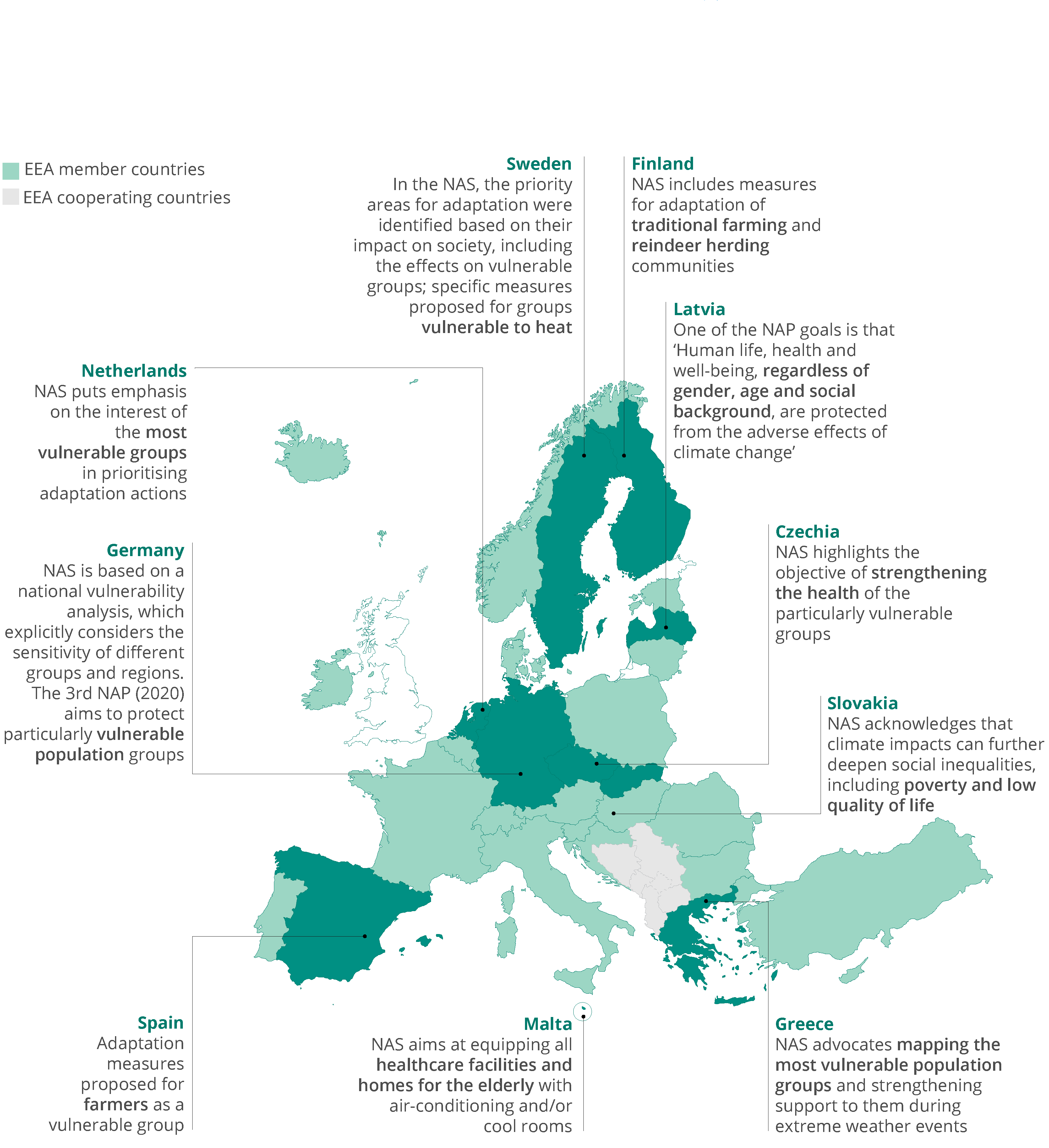

National policies: inclusion of just adaptation principles

Several EU Member States include the principles of justice as strategic goals in their national adaptation plans or strategies (ETC/CCA, 2021). Some of these also emphasise the importance of considering vulnerable groups and areas when selecting adaptation options and propose specific measures to address this (Figure 2). For example, nearly all 80 adaptation measures in the Latvian national adaptation plan address vulnerable groups, including improving early warning systems, providing access to free drinking water in public places, raising awareness among educational and social care institutions, and developing recommendations for social care stakeholders on health prevention measures during heatwaves (EEA, forthcoming).

Around one third of national adaptation strategies and national health strategies in EEA-38 countries explicitly include actions on identifying groups that are vulnerable to the health impacts of climate change (European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022e) (see the map viewer here). Some national policy documents (e.g., of Poland, Romania and Slovakia) identify the need for additional research on the health impacts of climate change on vulnerable groups and to raise awareness among medical personnel of how these impacts are intensified by pre-existing vulnerabilities.

Note: NAP, national adaptation plan; NAS, national adaptation strategy.

Sources: Adapted by the EEA from EEA (2018), ETC/CCA (2021) and EEA (forthcoming).

National heat health action plans (HHAPs) are key instruments to protect vulnerable groups during hot weather. According to WHO Europe (2021), among the 16 European countries that reported the existence of a national HHAP, 11 stated that their HHAP fully addresses vulnerable groups and the remaining five had partially implemented this component. Specific vulnerable groups at which heat-related health advice is targeted were the elderly (14 countries), chronically ill people (12), outdoor workers (10) and people who exercise outdoors (eight). Examples of specific measures, applied in France and Italy, include active surveillance by general practitioners (home visits and questionnaires) and out-of-hours calls to monitor vulnerable groups and collect information on their health status during the summer (WHO Europe, 2021).

Adaptative measures aimed at vulnerable groups can also be embedded in other types of national policies. For example, the 2019 German federal urban nature masterplan proposes creating more high-quality green spaces in disadvantaged areas, to encourage use by residents. Similarly, the Swedish Building and Housing Authority offers funding to projects that green disadvantaged neighbourhoods, with the aim of improving equity in access to urban green spaces (ETC/CCA, 2021).

Equity in subnational and local adaptation planning and actions

According to the EU adaptation strategy (EC, 2021b), the local level is the bedrock of adaptation. Most European countries recognise the crucial role of local authorities in implementing national adaptation strategies (EEA, 2020a). In addition, local authorities have the best knowledge of local population characteristics, locally occurring climate-related hazards and opportunities for engagement with local communities. Therefore, equity in planning and implementing adaptation measures matters most at the subnational and local levels.

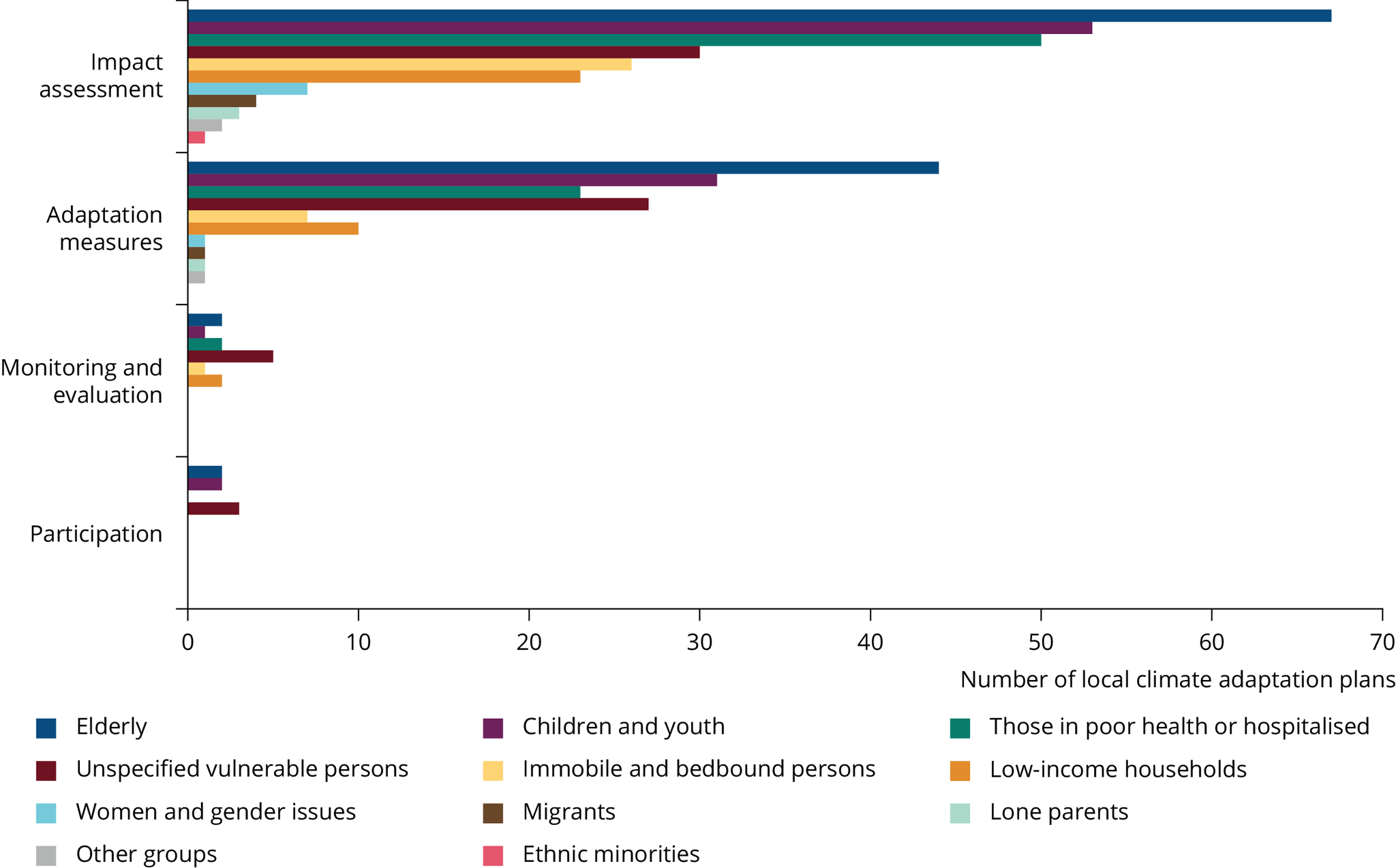

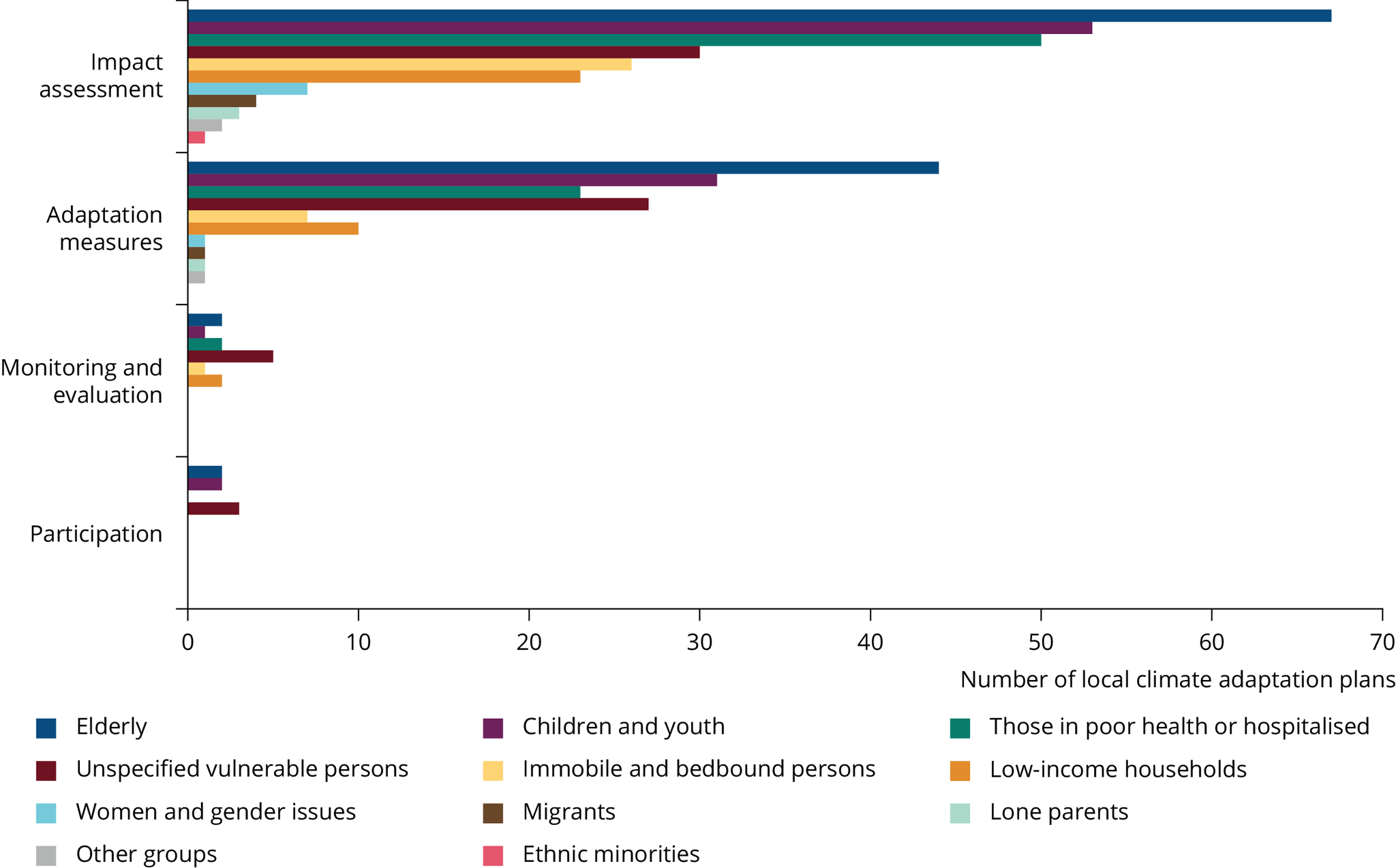

According to the EEA (2020) analysis of 150 European cities, the increased risk to already vulnerable people was the second greatest social impact of climate change recognised by city representatives. The local climate adaptation plans across Europe identify the elderly, first and foremost, as a vulnerable group, followed by children and those in poor health (Reckien et al., 2022; Figure 3).

Note: Based on analysis of 137 local adaptation plans of Urban Audit cities from 23 EU countries (EU-27 excluding Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Malta, where no adaptation plans were identified among the Urban Audit cities).

Source: Reckien et al. (2022).

More info...

Yet, projects and policies targeted at the most vulnerable groups were listed only 12th among the types of climate adaptation actions reported by cities (EEA, 2020a). Thus, issues of equity and social justice are still rarely considered in local-level adaptation planning and actions (ETC/CCA, 2018). Many climate adaptation measures focus on technological interventions, without accounting for the social characteristics of cities, and thus fail to address the unequal burdens of climate impacts (EEA, 2020a).

Further, while social inequality aspects are often considered at the local level in assessments of climate impacts, and to lesser extent in planning of adaptation measures, the participation of vulnerable groups in adaptation is very limited, and the implications of adaptive actions for the vulnerable groups are rarely considered in monitoring of adaptation outcomes (Figure 3). At the same time, Reckien et al. (2022) observe that the more recently published local adaptation plans tend to include equity aspects to a greater extent and consider a broader range of vulnerable groups in impact assessment and planning of adaptation measures compared to the older ones. The stronger engagement of local social care and health stakeholders in adaptation planning and implementation, the mainstreaming of adaptation in those sectors and the engagement of vulnerable groups themselves will help to ensure greater consideration of equity aspects in local adaptation planning. In addition, to learn which solutions are equitable and roll out their implementation, monitoring the social and economic effects of various adaptation options on different groups, and sharing experiences among local authorities, is urgently needed.

In conclusion, because of the complexity of both climate change and the multitude of societal challenges facing Europe, planning and implementing equitable adaptation responses require the involvement of decision-makers at various governance levels, from EU level to national and local authorities, with consistent policy messages emphasising the need for fairness in addressing the impacts of climate change. In addition, it calls for the engagement of public administration, civil society and private sector stakeholders from various fields, including:

- health, social care and social welfare — to address the underlying vulnerabilities

- spatial planning, urban design and housing — to address inequalities in exposure

- energy, transport and employment — to ensure synergy with the just transition towards a low-carbon economy (EEA, 2021b).

References

Attems, M.- S., et al., 2019, ‘Implementation of property-level flood risk adaptation (PLFRA) measures: choices and decisions’,WIREs Water 7(1), e1404.

Ciullo, A., et al., 2020, ‘Efficient or fair? Operationalizing ethical principles in flood risk management: a case study on the Dutch-German Rhine’, Risk Analysis 40(9), pp. 1844-1862.

Climate-ADAPT, 2017, ‘Heat hotline parasol — Kassel region’, Climate-ADAPT case study.

Climate-ADPAT, 2018, ‘Social vulnerability to heatwaves — from assessment to implementation of adaptation measures in Košice and Trnava, Slovakia’, Climate-ADAPT case study.

Climate-ADAPT, 2020a, ‘Adapting to the impacts of heatwaves in a changing climate in Botkyrka, Sweden’, Climate-ADAPT case study.

Climate-ADAPT, 2020b, ‘Urban stormwater management in Augustenborg, Malmö’, Climate-ADAPT case study.

Climate-ADAPT, 2022, ‘Support for distress associated with climate change in Finland — “the mind of eco-anxiety”’, Climate-ADAPT case study.

Covenant of Mayors, 2019, Dresden, a heat resilient city, Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy Europe.

EC, 2019, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘The European Green Deal’ (COM(2019) 640 final of 11 December 2019).

EC, 2021a, European Missions: adaptation to climate change — support at least 150 European regions and communities to become climate resilient by 2030: implementation plan, European Commission.

EC, 2021b, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions ‘Forging a climate-resilient Europe — the new EU strategy on adaptation to climate change’ (COM(2021) 82 final of 24 February 2021).

EC, 2022a, Cohesion in Europe towards 2050: eighth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion, European Commission.

EC, 2022b, ‘River floods’, EU Science Hub, European Commission.

EEA, 2018, Unequal exposure and unequal impacts: social vulnerability to air pollution, noise and extreme temperatures in Europe, EEA Report No 22/2018, European Environment Agency.

EEA, 2019a, Climate change adaptation in the agriculture sector in Europe, EEA Report No 4/2019, European Environment Agency.

EEA, 2019b, Healthy environment, healthy lives: how the environment influences health and well-being in Europe, EEA Report No 21/2019, European Environment Agency.

EEA, 2020a, Urban adaptation in Europe: how cities and towns respond to climate change, EEA Report No 12/2020, European Environment Agency.

EEA, 2020b, Monitoring and evaluation of national adaptation policies throughout the policy cycle, EEA Report No 6/2020, European Environment Agency.

EEA, 2021a, ‘Global and European temperatures’, European Environment Agency.

EEA, 2021b, Exploring the social challenges of low-carbon energy policies in Europe, Briefing No 11/2021, European Environment Agency.

EEA, 2022, ‘Who benefits from nature in cities? Social inequalities in access to urban green and blue spaces across Europe’, European Environment Agency.

EEA, forthcoming,EEA assessment report on state of play and way forward from the 2021 reporting on national adaptation actions, European Environment Agency.

ETC/CCA, 2018, Social vulnerability to climate change in European cities — state of play in policy and practice, ETC/CCA Technical Paper No 1/2018, European Topic Centre on Climate Change Impacts, Vulnerability and Adaptation.

ETC/CCA, 2021, Just transition in the context of adaptation to climate change, ETC/CCA Technical Paper No 2/2021, European Topic Centre on Climate Change Impacts, Vulnerability and Adaptation.

European Climate and Health Observatory, 2021a, ‘Exposure of vulnerable populations to heatwaves’.

European Climate and Health Observatory, 2021b, ‘Vulnerability to extremes of heat in Europe’.

European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022a, Climate change impacts on mental health in Europe — an overview of evidence.

European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022b, ‘Exposure of vulnerable groups and facilities to flooding and heat’.

European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022c, ‘Flooding’.

European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022d, ‘Wildfires’.

European Climate and Health Observatory, 2022e, Climate change and health: the national policy overview in Europe.

Eurostat, 2012, ‘Share of population living in a dwelling not comfortably cool during summer time by income quintile and degree of urbanisation’.

Eurostat, 2020, ‘Population projections in the EU’, Eurostat Statistics Explained.

Filčák, R., 2012, ‘Environmental justice and the Roma settlements of eastern Slovakia: entitlements, land and the environmental risks’,Czech Sociological Review 48(3), pp. 537-562.

Global Covenant of Mayors, 2018, Global Covenant of Mayors: common reporting framework — version 6.1, Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy.

Hickman, C., et al., 2021, ‘Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey’, The Lancet Planetary Health 5(12), pp. E863-E873.

Hudson, P., 2020, ‘The affordability of flood risk property-level adaptation measures’,Risk Analysis 40(6), pp. 1151-1167.

IPCC, 2014, Climate change 2014 — synthesis report: summary for policymakers, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

IPCC, 2022, Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Kind, J., et al., 2019, ‘Social vulnerability in cost-benefit analysis for flood risk management’,Environment and Development Economics 25(2), pp. 115-134.

Reckien, D., et al., 2022, ‘Plan quality characteristics of Local Climate Adaptation Plans in Europe’; DANS, https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xd6-w7pc.

Tesselaar, M., et al., 2020, ‘Regional inequalities in flood insurance affordability and uptake under climate change’Sustainability 12(20), 8734.

van Daalen, K., et al., forthcoming, ‘The 2022 Europe report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: towards a more climate resilient future’, submitted toThe Lancet Public Health.

UN Sustainable Development Group, 2022, ‘Universal values — principle two: leave no one behind’, United Nations Sustainable Development Group.

WHO Europe, 2021, Heat and health in the WHO European region: updated evidence for effective prevention, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe.

Identifiers

Briefing no. 09/2022

Title: Towards ‘just resilience’: leaving no one behind when adapting to climate change

EN HTML: TH-AM-22-009-EN-Q - ISBN: 978-92-9480-480-8 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/179019

EN PDF: TH-AM-22-009-EN-N - ISBN: 978-92-9480-479-2 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/043692

Document Actions

Share with others