Participatory foresight process

The EEA has been developing its foresight and systems thinking activities to provide timely and integrated assessments to guide its work on sustainability. As part of this, a participatory process led by the EEA informed this briefing. This process involved a group of experts — both from the EEA and external — with backgrounds related to mobility, transport, and urban, air and noise pollution.

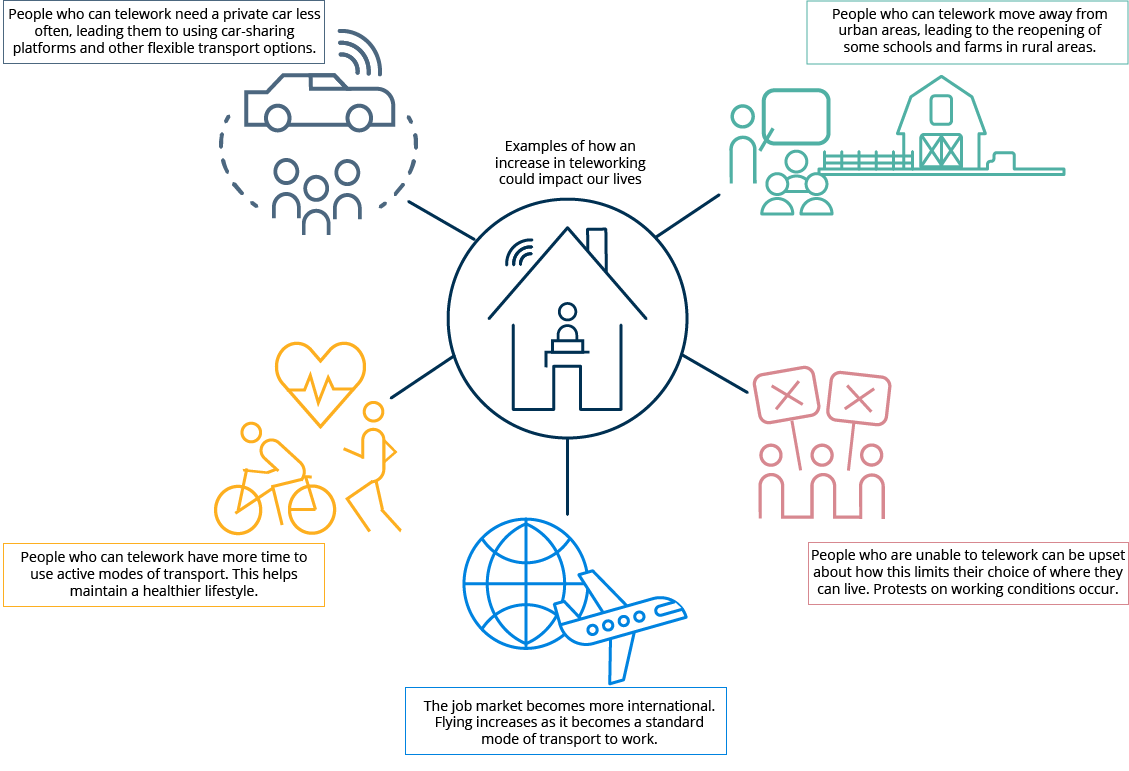

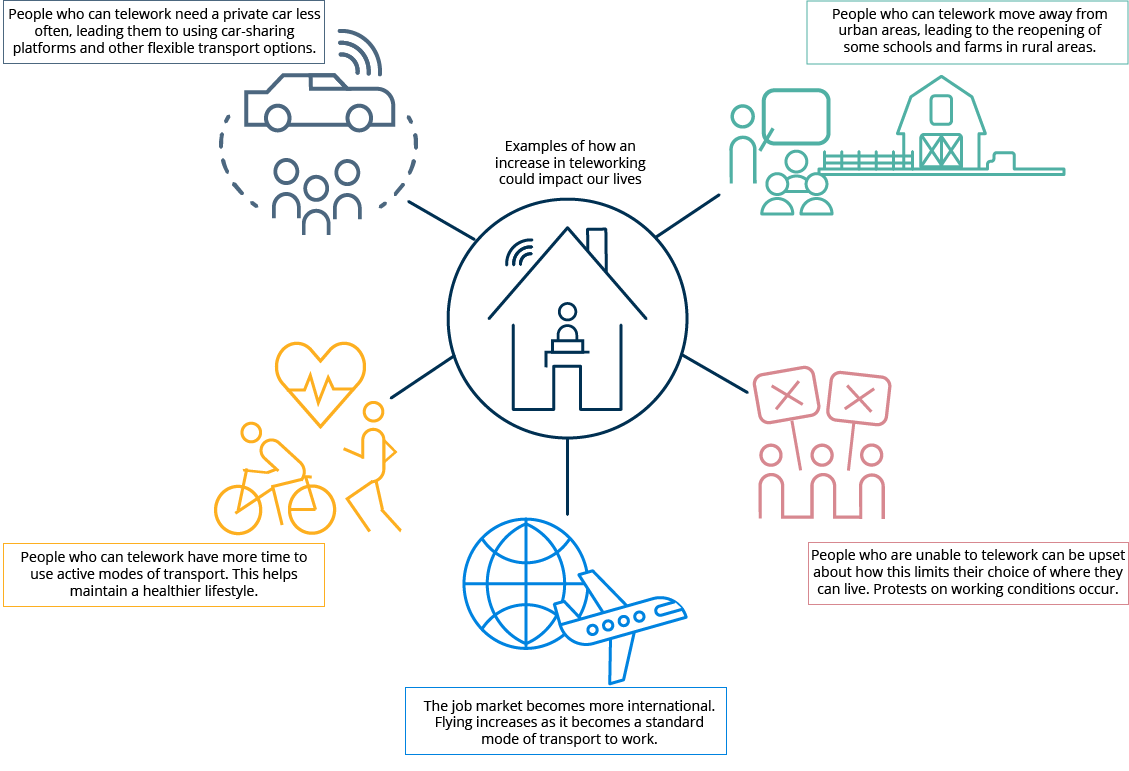

The first step was a participatory horizon scanning process which led to the identification of 139 signals that indicate how the urban mobility sector is evolving. These signals were then grouped into 17 emerging trends and discussed in two participatory online workshops. Several of those emerging issues were related to teleworking and the group of participants selected teleworking as a priority emerging issue. This briefing reports and expands on the main discussion points the participants raised on the topic and subsequent research (see Figure 1).

Mobility, lifestyles and sustainability challenges

Teleworking was possible before the pandemic

Ever since the industrialisation and mechanisation of agricultural practices, a growing majority of Europeans has been assigned to a workplace away from home (EEA, 2019a). The resulting necessity to commute back and forth has largely impacted modern life and overwhelmingly driven urbanisation patterns associated with a car-centric and polluting lifestyle, with high impacts on the environment and our health (EEA, 2023b, 2020, 2021b, 2019b, 2022c, 2023a, 2023c).

Therefore, one of the most sustainable ways of working involves no commuting or travelling at all. While unimaginable for many of us just four years ago, COVID-19 accelerated digitalisation (EEA, 2019a) — particularly of the way we work, shop and interact socially. Even though it came with significant limitations, the obligation to work online showed both employers and employees that current technologies could enable a functional alternative to commuting.

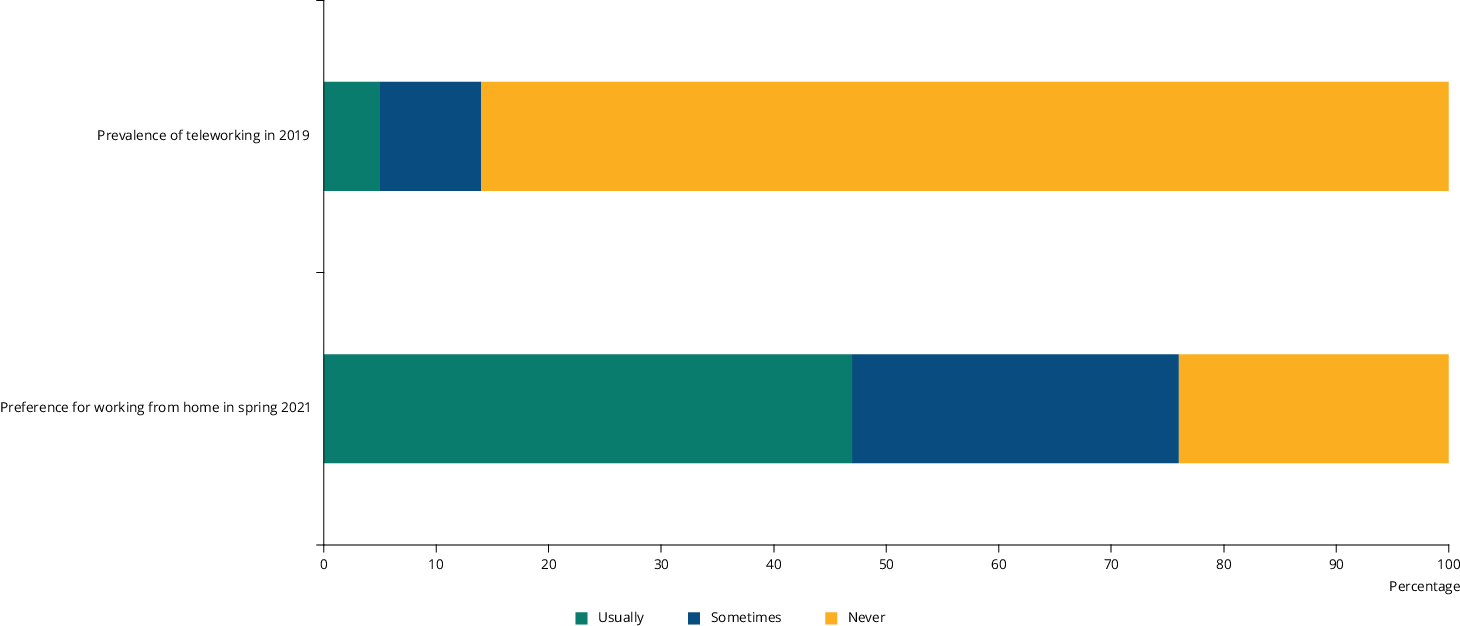

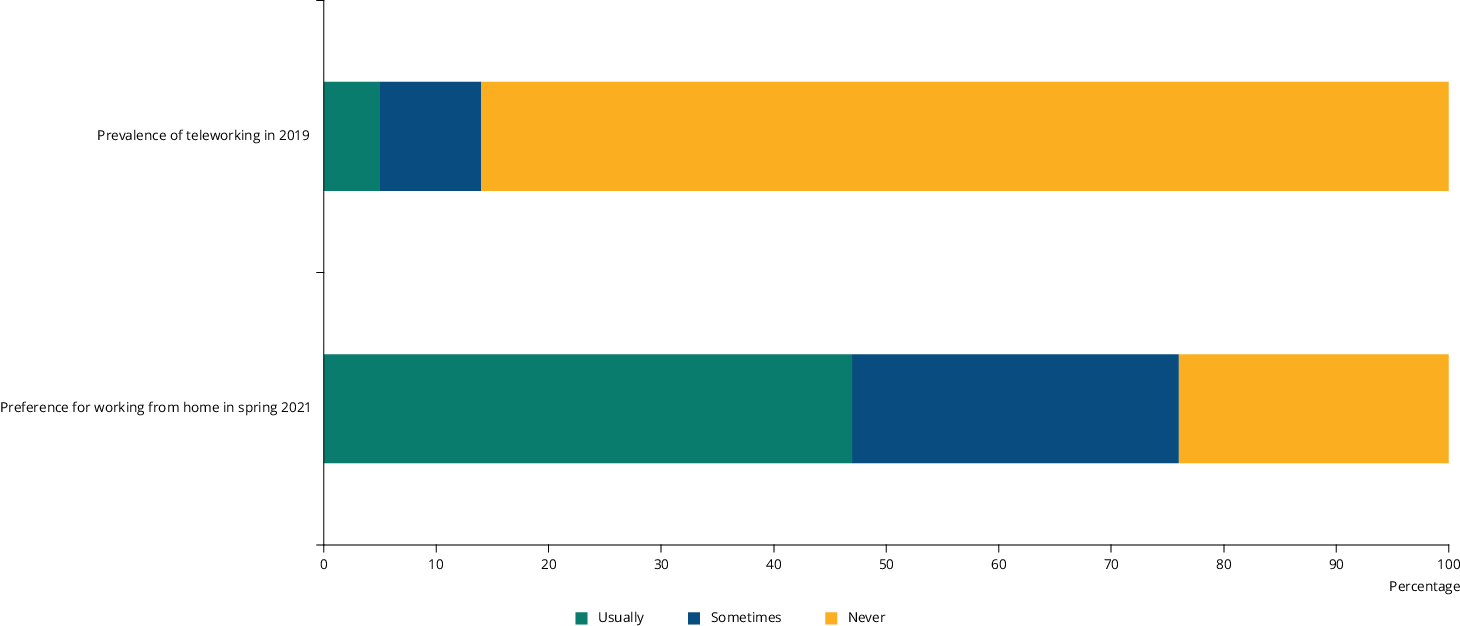

In response to the sudden restrictions imposed at the beginning of the pandemic, 10 EU Member States adopted new regulations on teleworking. The number of countries that have since enshrined the right to telework in their national policies has doubled (Eurofound, 2022b). Teleworking on a European scale is now an emerging trend: most surveys carried out since the lockdown periods indicate that the majority of employees who have the option to telework prefer the flexibility of a hybrid work approach, working at home usually or sometimes (JRC, 2020; Ahrendt et al., 2021; Boyon, 2021; Lund et al., 2021; Marcus et al., 2022) (see Figure 2). The question is now whether the 37% of workers in the EU who are allowed to telework will continue to do so in the absence of further lockdowns, despite associated limitations such as the need to dedicate space at home for working, challenges to work-life balance and risks of feeling isolated (Marcus et al., 2022).

Note: Answers ‘daily’ and ‘several times a week’ in the source material are combined and presented here as ‘usually’. Answers ‘several times a month’ and ‘less often’ are combined and presented here as ‘sometimes’.

Sources: Eurostat (2023); Ahrendt et al. (2021).

Explore different chart formats and data here

Redefining the office space

Hybrid working patterns could change the demand for office space, giving rise to questions about office needs in terms of capacity or location (Economics Observatory, 2020). Under a hybrid working scenario, workers would go to offices less often — and, when they did, they would most likely use a shared or flexible space. This flexibility in work organisation based on space sharing encourages ‘interaction, communication, control of time and space, and satisfaction with the workspace’, but sacrifices privacy and may make it more difficult for some workers to concentrate (Engelen et al., 2019). A broad transition to shared spaces could also, in the short to medium term, reshape how office workers view work and home — and how they use and balance both.

While evidence indicates that most employees are keen to further adopt hybrid working (Ahrendt et al., 2021), employers might be less enthusiastic about embracing it as a permanent model. According to KPMG’s 2021 CEO outlook survey, conducted in February/March 2021, a significant number of CEOs of some of the world’s leading companies intended to offer staff more flexible working options and invest in shared office spaces (KPMG, 2021). The survey found that over a fifth (21%) of CEOs planned to or had already cut down their office spaces. However, this is significantly lower than the figure reported in 2020: at the height of COVID-19 lockdowns, almost 69% of CEOs said that they were planning to reduce their office footprints and 51% said that they were considering investing more in shared office spaces. Yet in 2021, only around one-third of respondents (37%) said that they had introduced (or planned to introduce) long-term hybrid working patterns (KPMG, 2021).

More options for work and finding work

On a smaller scale, the buzz around the hybrid working model is inspiring some employers to pay more attention to ‘third places’: spaces for working other than the office or home, such as co-working spaces, cafes or other public places. Although this is a new market and no numbers are publicly available to date, an increase in the number of co-working spaces has been observed over the past few years (Statista, 2021). Part of the larger sharing economy, these spaces offer the possibility of separating the home and workplace while still allowing people to work from a place (ideally) closer to home — making commuting more sustainable. While many co-working spaces have suffered from repeated lockdowns and strict social distancing requirements, they have also benefited from the rapid development of teleworking options and the realisation by many office workers that they can work elsewhere (Ceinar and Mariotti, 2021). This additional work location option could lead to employers and employees expanding the areas in which they seek work or collaborators even further — for instance internationally — which would make the labour market even more dynamic.

Urbanisation and suburbanisation

The new opportunity to put distance between where we work and live prompted some urban inhabitants to seek homes outside city centres, namely in suburban or rural areas (EEA, 2021a; Ahrend et al., 2022). While it is still too early to spot clear COVID-related trends influencing urban landscapes, part of the motivation for such a move following a pandemic is to make it easier to access space and nature in the event of further lockdowns or curfews. The need to allocate part of the home as office space could also push those who can afford it to look for bigger houses that can accommodate new office space without limiting living areas.

When they are eventually approved and rolled out on a large scale, autonomous vehicles (AVs) could also play a role in encouraging people to move away from urban areas. Combining hybrid working with the use of an AV would mean that, on the few days a month that a person travels to their office to work, they could focus on activities other than driving during the commute, making a longer commute seem less of a burden (Zhong et al., 2020).

It is far from certain that this would lead to more sustainable work practices and lifestyles, and AV technology is still being developed. But, eventually, AV availability among European residents — combined with the high cost of housing in cities — could encourage growing numbers to reconsider where they live and opt for greener and more affordable rural locations. This would come with the major downside of significantly increasing car numbers and traffic congestion if no mitigating measures, such as road tolls or urban access restrictions, are put in place (EEA, 2023d). A sharp increase in the number of AVs would also amplify trade-offs associated with the production of electric vehicles. Specifically, battery manufacturing demands high levels of raw material extraction, which is associated with hazardous mining work and child labour (Mancini et al., 2020; EEA, 2022b). Therefore, more scrutiny of working conditions is needed to avoid worsening these health and social issues.

A limited reduction in environmental costs

During the foresight process, participants also considered how teleworking could decrease car-related pollutant emissions, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and noise pollution because of the overall reduction in commuting by car it could lead to. This is an appealing scenario. However, most recent studies estimate that such direct effects would be very slight — amounting to between a 4% and 7% decrease in countries’ external environmental costs of passenger transport. As explained in the EEA’s Transport and environment report 2022, particularly in Annex 1 (EEA, 2023d), these figures might even be optimistic. This is because they rely on simplifying assumptions about the numbers of teleworkers and do not include rebound effects, which could be numerous. For example, one potential rebound effect of less traffic is that it could lead to new car traffic as drivers look for easier and faster ways to commute. Furthermore, as cars become more environmentally-friendly in terms of GHG emissions and therefore emit less per kilometre, these figures could decrease even further. Similarly, flexible working and a more internationalised labour market could lead to more air traffic. This is because flying for professional reasons could become more common if, for instance, a person is required to attend regular meetings in person at a remote office location (Chokshi, 2022).

It is equally important to consider that teleworking itself entails some environmental costs. These include higher energy consumption at home, the production of extra information technology (IT) and office materials, and the extra power needed for servers and data exchange. Calculating these costs and comparing them with those of traditional working patterns is difficult, as it is not as easy to distinguish between energy consumed during work and non-work time and activities at home. However, the environmental costs, benefits and other rebound effects of teleworking need to be accounted for. They should be carefully monitored and researched, and relevant mitigating measures and policies should be developed to ensure that teleworking (and digitalisation as a whole) is sustainable (Eurofound, 2022a).

Challenges for a just transition

The participatory work supporting this briefing took place during some of the strictest lockdown periods in 2020 and 2021. Since then, Europe has been hit by an energy crisis, forcing many European residents to limit their energy use, or even relocate, for fear of not being able to pay their bills. This means that some people might not be quite as keen to work from home as before, as doing so would increase energy consumption in their own homes; instead, they may prefer to commute to work, where bills are covered by their employers.

This points to another aspect of teleworking that needs to be carefully addressed: working conditions at home. Numerous factors can influence how comfortable or efficient it is to work from home — such as internet connection stability, the space available per person, ergonomics and interference from others. Such aspects, linked to rapid digitalisation, are addressed by the European Commission’sEuropean Pillar of Social Rights action plan, which encourages social partners to explore measures that will ensure fair teleworking conditions and the right to disconnect (European Commission, 2021).

Finally, a change in commuting patterns and fewer workers being office-based could directly affect the supporting industries that ‘live off’ workers who commute to urban areas. This could lead to less money being spent in urban areas and on public transport, less demand for hospitality services and lower transport revenue. At the same time, a rise in teleworking, either from home or a third place, could lead to a more even spatial distribution of hospitality and transport services, as workers would be less concentrated in specific areas.

Potential effects of recurring infection periods

This briefing explores teleworking post-COVID, in a future where lockdown periods are mostly a thing of the past. However, pandemics remain a major threat and should be considered as such when reflecting on potential futures. During the strictest COVID-19 lockdowns, we observed behavioural changes resulting from the need to distance from one another and limit potential contagion risks. Many people preferred, and some still do, to avoid public transport, car sharing and even cycling in busy areas at times of high contagion rates (McKinsey, 2020). For many, especially the most physically vulnerable, online shopping became a much-needed alternative to traditional shopping.

If recurring periods of infection are seen in the future, we may also see fluctuations between teleworking, hybrid working and ‘traditional’ commuting patterns. This, combined with an increase in the number of people relocating outside cities, could lead to more people commuting by car and more last-mile freight transport. From an economic point of view, the EU has vowed to keep the green transition just as high on the agenda as resilience plans (European Commission, 2020). However, if other pandemics occur, incentives to invest in alternative mobility solutions such as shared autonomous vehicles and multimodal digital mobility services could be reduced. In effect, this could limit the options available for implementing the green transition.

Emerging work patterns

Recent transport studies estimate that hybrid working is likely to have only limited positive effects on environmental costs and pollution. However, the participants in this foresight process also pointed towards a possible deeper level of behavioural or indirect change — for example, downsizing office spaces or suburbanisation — that could result from broadly adopting hybrid working and teleworking (EEA, 2022a).

These changes in ways of working are not without trade-offs and potential rebound effects. This briefing explores only a few of them, and in-depth and proactive studies are needed to assess the potential impacts of hybrid working on our society, health and environment. The findings of such studies should inform the strategic and forward-thinking policy choices needed to navigate new work options and avoid triggering rebound effects and trade-offs that would hamper progress towards sustainability.

The move towards hybrid working has highlighted how our current work-life balance and connection to a fixed work space can suddenly be challenged by external events and the need to adapt to a ‘new normal’. Combined with strategic policy responses, this could ultimately help us revisit our reliance on commuting and our car-centric lifestyles. Moreover, we could rethink some aspects of our daily lives that seemed very established only a couple of years ago — especially those that limit our prospects for a more sustainable future.

References

Ahrend, R., et al., 2022, Changes in the geography housing demand after the onset of COVID-19: first results from large metropolitan areas in 13 OECD countries, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No 1713, OECD, Paris (https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/changes-in-the-geography-housing-demand-after-the-onset-of-covid-19-first-results-from-large-metropolitan-areas-in-13-oecd-countries_9a99131f-en) accessed 7 July 2022.

Ahrendt, D., et al., 2021, Living, working and COVID-19 (update April 2021): mental health and trust decline across EU as pandemic enters another year, Eurofound, Dublin (https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef21064en.pdf) accessed 6 December 2022.

Boyon, N., 2021, ‘Workers want more flexibility from their employers after COVID’, Ipsos (https://www.ipsos.com/en/return-to-the-workplace-global-survey) accessed 7 July 2022.

Ceinar, I. M. and Mariotti, I., 2021, ‘The effects of Covid-19 on coworking spaces: patterns and future trends’, in: Mariotti, I. et al. (eds),New workplaces — location patterns, urban effects and development trajectories, Research for Development, Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland, pp. 277-297.

Chokshi, N., 2022, ‘Airlines cash in as flexible work changes travel patterns’, New York Times, 21 October 2022 (https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/21/business/airlines-flex-work-travel.html) accessed 27 January 2023.

Economics Observatory, 2020, ‘Will coronavirus cause a big city exodus?’, Economics Observatory (https://www.economicsobservatory.com/will-coronavirus-cause-big-city-exodus) accessed 18 August 2022.

EEA, 2019a, Drivers of change of relevance for Europe’s environment and sustainability, EEA Report No 25/2019, European Environment Agency (https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/drivers-of-change) accessed 6 December 2018.

EEA, 2019b, Healthy environment, healthy lives: how the environment influences health and well-being in Europe, EEA Report No 21/2019, Europe Environment Agency (https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/healthy-environment-healthy-lives/download) accessed 16 December 2022.

EEA, 2020, Environmental noise in Europe — 2020, EEA Report No 22/2019 (https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/environmental-noise-in-europe) accessed 5 August 2020.

EEA, 2021a, ‘Urban sustainability in Europe — opportunities for challenging times’, European Environment Agency (https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/urban-sustainability-in-europe) accessed 10 April 2023.

EEA, 2021b, Urban sustainability in Europe — what is driving cities’ environmental change?, EEA Report No 16/2020, European Environment Agency (https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/urban-sustainability-in-europe-what) accessed 10 April 2022.

EEA, 2022a, ‘COVID-19: lessons for sustainability?’ (https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/covid-19-lessons-for-sustainability) accessed 1 December 2022.

EEA, 2022b, ‘Resource nexus and the European Green Deal’ (https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/resource-nexus-challenges-and-opportunities/) accessed 5 July 2022.

EEA, 2022c, Urban sustainability in Europe — post-pandemic drivers of environmental transitions, EEA Report No 6/2022, European Environment Agency (https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/urban-sustainability-drivers-of-environmental) accessed 31 March 2023.

EEA, 2023a, ‘Air pollution and children’s health’ (https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-pollution-and-childrens-health) accessed 24 April 2023.

EEA, 2023b, ‘European city air quality viewer’ (https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/air/urban-air-quality/european-city-air-quality-viewer) accessed 24 April 2023.

EEA, 2023c, ‘Europe’s air quality status 2023’ (https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/europes-air-quality-status-2023) accessed 24 April 2023.

EEA, 2023d, Transport and environment report 2022, EEA Report No 07/2022, European Environment Agency (https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/transport-and-environment-report-2022/), accessed 12 May 2023.

Engelen, L., et al., 2019, ‘Is activity-based working impacting health, work performance and perceptions? A systematic review’, Building Research & Information 47(4), pp. 468-479 (DOI: 10.1080/09613218.2018.1440958).

Eurofound, 2022a, Is telework really ‘greener’? An overview and assessment of its climate impacts, Eurofound, Dublin (https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/wpef22031.pdf) accessed 31 March 2023.

Eurofound, 2022b,Telework in the EU: regulatory frameworks and recent updates, Eurofound, Dublin (https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2022/telework-in-the-eu-regulatory-frameworks-and-recent-updates) accessed 19 December 2022.

European Commission, 2020, ‘Recovery plan for Europe’, European Commission - European Commission (https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/recovery-plan-europe_en) accessed 18 August 2022.

European Commission, 2021, The European Pillar of Social Rights action plan, European Commission (https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/111056) accessed 28 November 2022.

Eurostat, 2023, ‘Employed persons working from home as a percentage of the total employment, by sex, age and professional status (%)’ (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/LFSA_EHOMP__custom_899843/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=1a955ba3-e7ff-42b5-9449-69a6db8750ff) accessed 26 April 2023.

JRC, 2020, Telework in the EU before and after the COVID-19: where we were, where we head to, Science for Policy Briefs, Joint Research Centre, European Commission (https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-06/jrc120945_policy_brief_-_covid_and_telework_final.pdf) accessed 10 April 2023.

KPMG, 2021, KPMG 2021 CEO outlook, KPMG International (https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2021/09/kpmg-2021-ceo-outlook.pdf) accessed 5 July 2022.

Lund, S., et al., 2021, The future of work after COVID-19, McKinsey & Company (https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid-19) accessed 5 July 2022.

Mancini, L., et al., 2020, Responsible and sustainable sourcing of battery raw materials, Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg (https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC120422) accessed 25 April 2022.

Marcus, J. S., et al., 2022, COVID-19 and the accelerated shift to technology-enabled work from home (WFH), Bruegel AISBL and The German Marshall Fund of the United States (https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/COVID-19-technology-and-WFH.pdf) accessed 31 March 2023.

McKinsey, 2020, ‘A playbook for mobility service providers beyond COVID-19’ (https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/why-shared-mobility-is-poised-to-make-a-comeback-after-the-crisis) accessed 5 July 2022.

Statista, 2021, ‘Flexible office space Europe and the UK — statistics & facts’, Statista (https://www.statista.com/topics/5912/flex-workspaces-in-europe-and-the-uk/) accessed 12 December 2022.

Zhong, H., et al., 2020, ‘Will autonomous vehicles change auto commuters’ value of travel time?’, Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 83, 102303 (DOI: 10.1016/j.trd.2020.102303).

Identifiers

Briefing no. 26/2022

Title: From the daily office commute to flexible working patterns — teleworking and sustainability

EN HTML: TH-AM-22-030-EN-Q - ISBN: 978-92-9480-536-2 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/34252

EN PDF: TH-AM-22-030-EN-N - ISBN: 978-92-9480-537-9 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/960387

Document Actions

Share with others